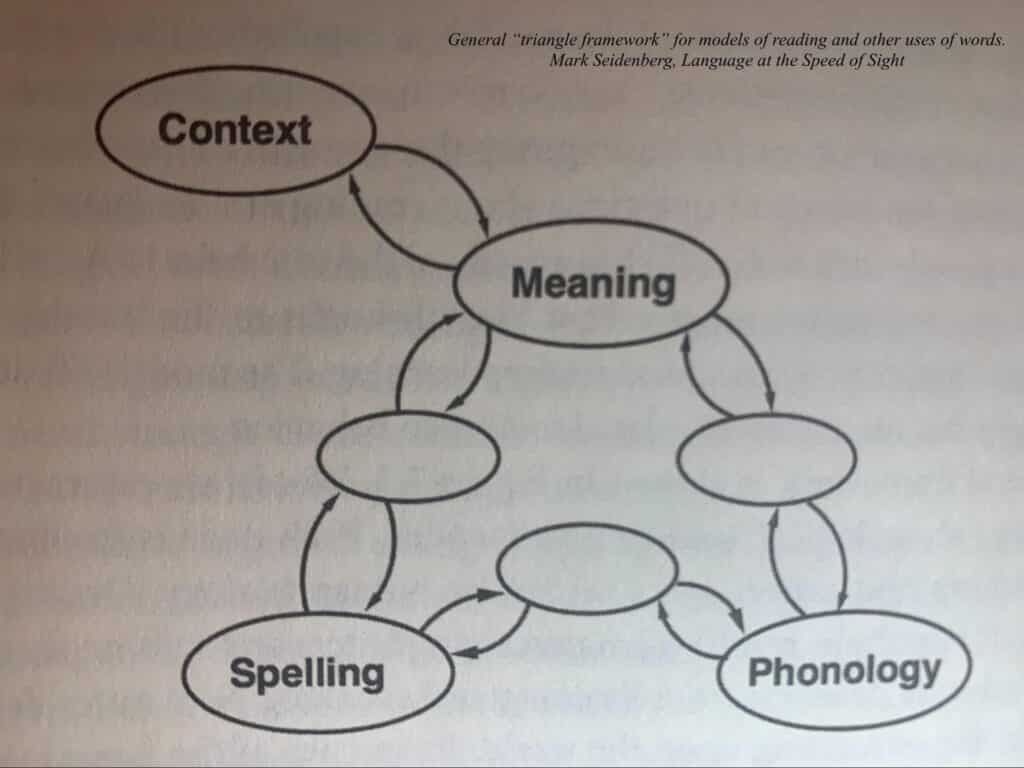

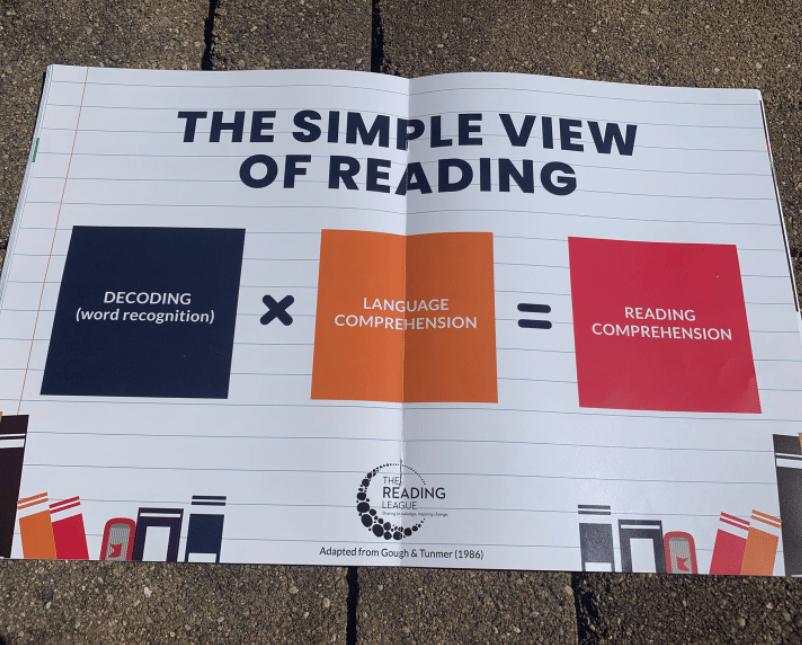

- the automatic recognition of the words on the page, as well as

- understanding of the vocabulary and concepts included in the text.

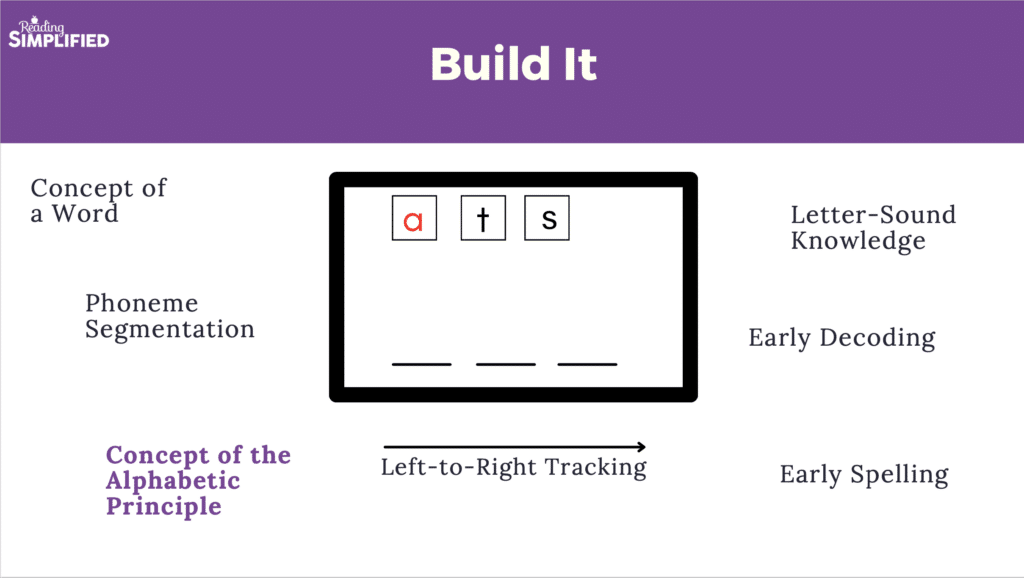

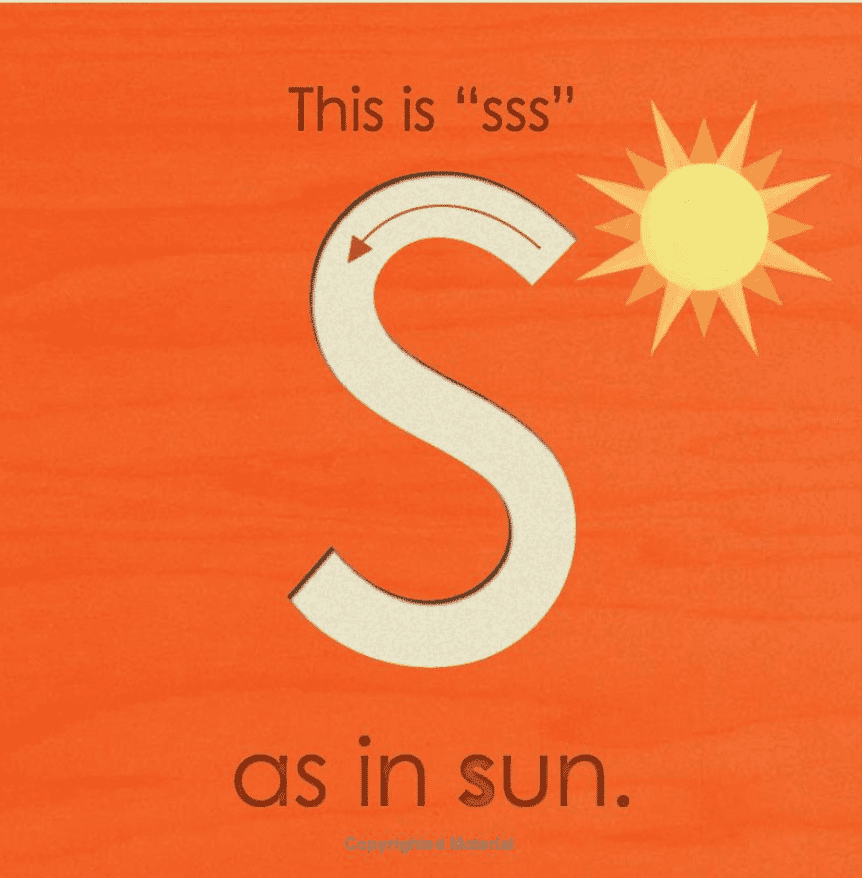

(By “decoding” the researchers mean recognizing words via understanding of the alphabetic code–that letters and letter combinations represent sounds in words. The term “word recognition” incorporates this concept of “de-coding” as well as the skill of automatic word identification from practice.)

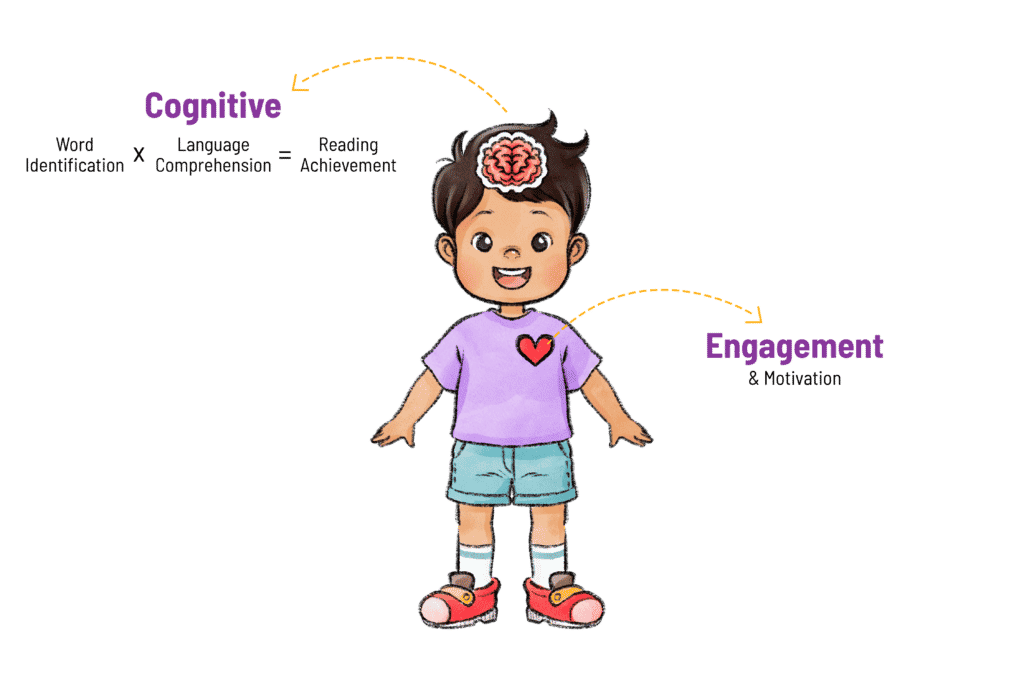

One can’t have strong reading comprehension without strong processes in both domains of word recognition and language comprehension. At every phase of a reader’s development, parents, teachers, and the broader community can support both of these domains in order to produce confident, successful readers. In this article, we’ll examine how boosting both language and word recognition will enable our budding readers to succeed.

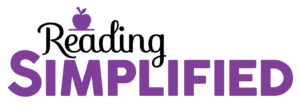

In the child model below, notice the Cognitive aspects of learning to read (i.e., the Simple View of Reading) as represented by the brain image. (Other affective aspects, such as Engagement and Motivation, as well as interpersonal relationships also exert powerful aspects on the child’s language and literacy development.)