What’s the first step we should take when teaching someone to read? Most people probably assume it's teaching the letters of the alphabet. However, the alphabet letters are NOT really the true foundation of how our written code works. The foundation is actually the alphabetic principle, which is the concept that our written language is a code for sounds.

Written words consist of sounds (phonemes) that are represented by letters and letter combinations (graphemes). Once a child unlocks the alphabetic principle, she opens a doorway to becoming a good reader.

In this article, we explore why understanding the alphabetic principle is the true first step in learning to read. We’ll also show how you can use the Build It activity to help pave the way for the alphabetic principle...on the road to a lifetime of reading.

What is the Alphabetic Principle?

The alphabetic principle is the concept that our written language is a code for sounds. All words are built from sounds, or phonemes, which in written form are represented by letters and letter combinations, called graphemes. In other words, graphemes are a code for sounds (phonemes). Learning to read is the work of cracking this code. The alphabetic principle is the first insight one must have in order to begin “de-coding” more and more words.

The alphabetic principle is the first insight one must have in order to begin “de-coding” more and more words.

To read unfamiliar words, the reader must first understand the idea that the sounds in words can be represented by squiggles on a page. This is not an idea that comes naturally to most humans. Indeed, what an amazing accomplishment the creation of an alphabetic writing system was as this form of communication revolutionized the world. Yep, even a bigger deal than the iPhone or TikTok!

We don’t recognize words by how tall or short or long they are; we don’t recognize words by just the first or the last letter sound. Rather, we translate particular symbols as visual representations of individual sounds (phonemes)--in their very specific, left-to-right order--in words.

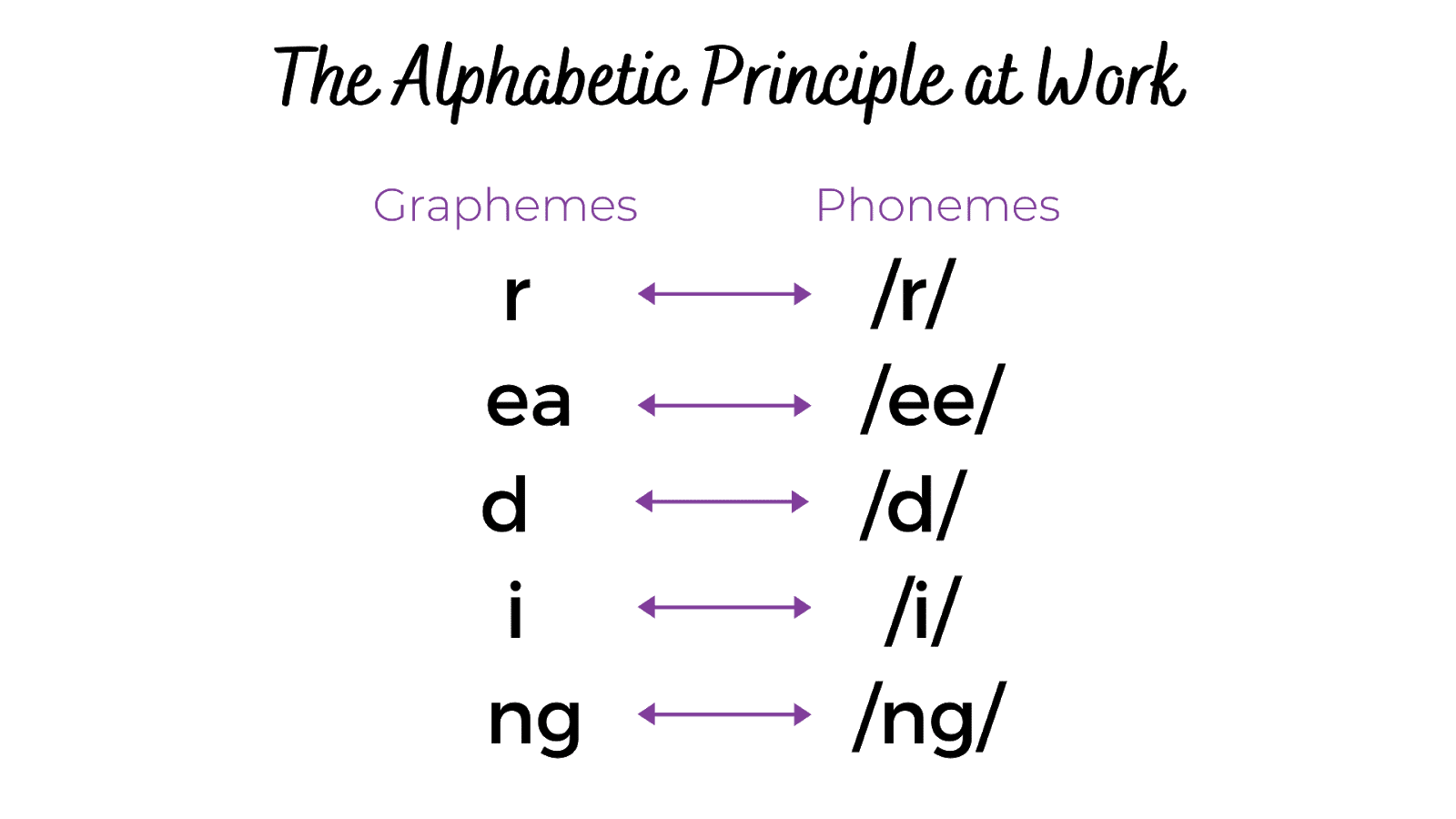

For instance, to crack the code of the word “reading,” one needs to know that these graphemes represent these phonemes:

The process of decoding sounds and symbols as in the image above is the work the developing reader needs to practice and grow in. The very first step is even recognizing that a code exists to help us read and that this code is a code of sound-symbol associations.

Why Begin with the Alphabetic Principle Instead of the Alphabet Letters?

U.S. culture begins the teaching of reading by teaching the alphabet. First, we usually guide our 2, 3, 4, and 5 year-old children to learn to recognize the letter names of the 26 letters of the alphabet, right?

But the alphabet is just a supporting player in how the code works. The true first step in learning to read is grasping the concept that sounds in words are pictured with letters and letter-combinations. That’s an “Aha!” we should be teaching our preK students to grasp.

And when we think we’re giving students the building blocks by teaching the alphabet letters, we’re actually leaving important information out. :O

Our written code is not exactly based on the 26 letters of the alphabet...it’s based on the 44(ish) sounds in our language! The letters are just tools to build other representations of phonemes. For instance, the letter “s” can represent the

- the /s/ in “sit,"

- the /z/ in “dogs,”

- part of the /sh/ in “shop,” and

- even the less common /sh/ in “sure” or the /zh/ in “usual.”

Some representations of the /s/ sound include more than just the letter “s” too, as in the “se” in “house.” And the “ce” in “nice” doesn’t even include the letter “s!”

Bonus trivia: the /s/ sound is the second phoneme often represented by the “x,” as in “box.” Do you hear the /ks/?

Here’s another mind-bender....

You may have been taught--and taught this yourself as I once have--that “the vowels are a, e, i, o, u, and sometimes y.” But this is an alphabet-centric view that ignores the true nature of our code. Actually, there are about 15 vowels, including /oy/, /ow/, and /er/. The so-called long and short vowels are only part of our English vowel sounds.

Thus, while most teachers start early readers off by talking (and singing!) the alphabet, this is not the introduction that researchers have demonstrated reveals the alphabetic principle. Instead, through experiments with preK children, researchers have revealed that the alphabetic principle is induced by tuning in kids to the sounds of words and pairing these sounds with specific letter combinations(1).

Teaching the alphabetic principle helps students understand that:

- Our written language is a code for sounds, and

- These sounds (phonemes) can be represented with a lot of different letters and letter combinations (graphemes).

(In other words, the 26 letters of the alphabet alone do not depict the true nature our sound-based spelling system works.)

This almost feels like a secret code, and it kind of is!

Crack this code, and your students will be on the road to reading with confidence!

The Alphabetic Principle Is NOT the Same as the Alphabet

Are you getting the idea now of how the alphabetic principle is different from the alphabet itself? They’re related, of course, but when we talk about the alphabetic principle, we’re just thinking of the concept about how our code works. In contrast, we define the term “the alphabet” as related to the specific recognition of the letters and/or sounds of the 26 letters of the alphabet.

Thus, the alphabetic principle is the big concept or idea that one can learn all at once and have for a lifetime, but the alphabet, and other graphemes such as “sh” or “igh” are bits of phonics information that will take time to learn, bit by bit.

Significantly, the sounds, in particular, help build the concept of the alphabetic principle, but the letter names themselves can actually trip young kids up.

Why?

The initial sounds in the names of some letters, such as “s,” “h,” or “n” do not begin with the sound we say when we see that letter….

Say the letter “s” slowly. What sounds do you hear?

/e----ssssss/.

Did you notice how the name of the letter “s” begins with the short “e” sound, as in “egg?”

So what happens when a very beginner is trying to read a word like “sat” and he begins with /e----ssss/? He’s unlikely to make the connection that the “s” in “sat” is the /s/ sound.

As a result he may be less likely to grasp the concept of the alphabetic principle. Wah. Wah.

It’s even crazier for the letter “h.” What sounds do you hear in that letter?

/aytch/! Yikes!

What does that have to do with the first sound in the word “hen?”

That’s why we suggest avoiding the letter names until the child has the concept of the alphabetic principle and is on his way to good decoding strategies. The letter names come quickly after a child is already reading. At that point, they will have plenty of mental “hooks” on which to stick.

In addition, even if children are learning the letter-sounds themselves, they still may not “get” the concept of the alphabetic principle. This is especially true if the letter-sound instruction is divorced from real words and phonemic connections. (I write more about the importance of integrating all of these concepts here.)

After you understand the distinctions I’m writing about here among the alphabetic principle, the alphabet, letter-sound knowledge, and phonemic awareness, you won’t let this trip up your students!

“Imagine going to work for a shipbuilding company. You go to work the first day and are schooled in all the different types of bolts, screws, and nails. You learn their names, the different sizes, and the different types, but you never learn that their purpose is to join pieces of metal and that those pieces of metal are used to build ships! Although this situation is clearly ridiculous, it is actually analogous to what we see in some prekindergarten and kindergarten classrooms. Children are being taught to name letters or even identify the sounds that the letters represent, but they are unclear about why they are learning it. Letter-sound knowledge is being learned in a vacuum; the child has no context for how to use the information, no ‘big picture’” (Duke & Mesmer, 2019). (2)

The Fastest Way to Teach the Alphabetic Principle

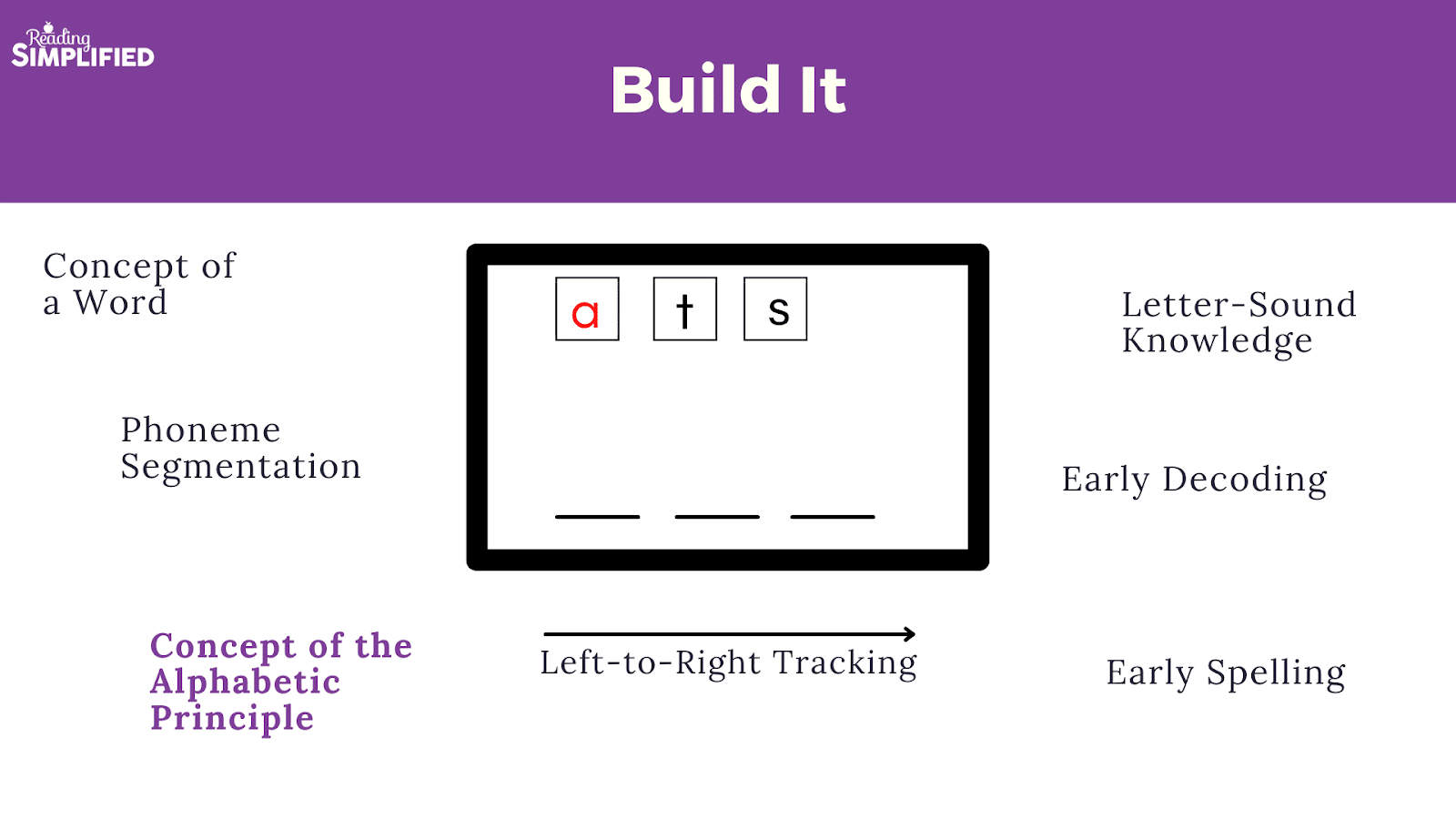

The fastest way I’ve found to teach the alphabetic principle to early readers is to draw students’ attention to how to connect letters to their most common sound or sounds. One easy way to do this is with the word work activity, Build It.

Build It demonstrates:

- The alphabetic principle,

- The concept of a word,

- Left-to-right tracking,

- Letter-sound knowledge,

- Phonemic segmentation,

- Early decoding, and

- Early spelling.

It sounds like a lot to cover, but the exercise is very approachable. The key to Build it is teaching the letter sounds and all of these concepts like the alphabetic principle in context, not in isolation.

How to Know Whether or Not Your Student Is Ready for Build It

Introducing letter-sound relationships to young readers is a lot easier than you might think, especially when you use Build It to help speed things along! But how do you know if your student is ready for Build It?

In the video below, there’s a ton of great information about the alphabetic principle, and about the Build It activity. One clip in particular, about three and a half minutes in, shows a short session working with a four-year-old boy who is not quite ready for the Build It activity.

Take a look at this video.

In the clip above around the 3:30 mark, this student doesn’t yet have the background knowledge of letter sounds, and he struggles to perceive the sounds at the beginning of words. (This is also called weak phonemic awareness, in particular phoneme segmentation. He couldn’t yet segment the words properly without the teacher doing the work for him.)

As a result, he probably doesn't yet get the concept of the alphabetic principle. He doesn't yet understand how our written language’s ‘secret code’ works.

This young four-year-old wasn’t quite ready—and that’s perfectly okay! Different kids are ready at different times. He needs some preparation first, but this early introduction to letter sounds in the context of Build It acted as a great testing ground to determine his readiness.

You can do the same with your students. Check in periodically with an activity like Build It to determine if they are ready to start learning more about our code.

Paving the Way with Build It

The Build It activity encourages kids to build one word at a time using manipulatives first. In this activity, we focus on the sound of the letters, rather than teaching the letter names or letter sounds in isolation.

Build It helps students to begin learning to read in a multi-sensory way, helping them to develop these 3 most vital early concepts and skills:

- How our written language code works,

- How to segment words into individual sounds (phonemes), and

- Recognizing letter-sounds.

In the same video, you’ll also see at around the seven and a half minute mark a three-and-a-half-year-old boy who is definitely ready for the Build It activity!

He is hearing the sound, and understanding the concept of the sound. In other words, he can segment fairly easily, and demonstrates his phonemic awareness well. This shows that he is the perfect candidate to start the Build It activity.

Later on in the video, at around nine minutes in, you can see a four-year-old girl who was ready and able to engage with the Build It activity.

She was picking it up, making connections, and building words with confidence! You can see how she already knew some letter sounds, and was practicing phonemic segmentation, letter-sound knowledge, and the alphabetic principle in the activity.

She demonstrated everything that the Build It activity is designed to teach early readers. She found the phonemic segmentation to be a little more difficult when it came to the middle vowel, which is typical. However, she did manage to spell the word and get the concept of the alphabetic principle and is well on her way to learning how to decode.

Struggling with the Build It Activity

If your students get it, awesome! If you find that your students continue to have issues with Build It after several coaching attempts, it’s time to take a break from this activity.

Some kids are just stronger at perceiving the sounds than others, and that’s totally fine. If kids were never taught the concept of the alphabetic principle and don’t connect letters with sounds, they’re more likely to struggle. Once your child’s phonemic awareness improves a tad, s/he will begin to crack the code and see how sounds and symbols match up to make words.

The first 2 activities suggested below will be helpful preparation for these students who are struggling with Build It. In addition, we have a video example that can be sent to parents to encourage them to practice phoneme segmentation with their child at home. This oral-only approach is another way to prepare the child for Build It and it can be done on-the-go as in the car trip game demonstrated in the video. I also have a few other tips in this guest post at Imagination Soup.

If you need more persuasion for why to start with the alphabetic principle and not the alphabet, you can find lots of tips on our previous video and blog – “How the Alphabet Done You Wrong…And What to Do Instead.”

3 Easy Steps to Early Reading Success

Even though thousands if not millions of children are confused about the alphabetic principle, it’s actually not that hard to guide a child to “get it.”

Are your students not quite ready for Build It? Here are 3 easy ways to build the alphabetic principle in children as young as 2 or 3 years-old to help them prep:

- Storybook tracking of print and phonemes,

- Phoneme identity matching activities, and

- Build It activity

Let’s dig in….

- Storybook Tracking of Print and Phonemes. When you’re enjoying a book with a child, or a group of children, occasionally draw your finger under each word carefully. Occasionally exaggerate and elongate the sounds in the word as your finger runs underneath the word.

For instance, perhaps you’re reading Where the Wild Things Are. Try reading this sentence like this as you drag your finger under each word slowly:

“And /mmmmmma----kss/, Max, the king of all /wwi-----llllllld/, wild things, was lonely and wanted, to be where someone loved him best of all.”

So, one is drawing attention to the sounds in words by exaggerating the sounds in a word, here and there. This is a painless way to implicitly hint at the alphabetic principle.

Occasionally, note what sound a word begins with (“So Max’s name begins with the /mmmm/ sound. Do you see the /mmmm/ here?”) Researchers have tested a somewhat similar approach called “print referencing” and have found that it does cue children into important early information about how the code works.

For instance, Laura Justice and her colleagues led an experiment of 23 preK classrooms of children with economic, social, or developmental risks, including 9 Head Start settings(3). One group of preK teachers read storybooks to the children in a “business as usual” approach. The experimental group of teachers, on the other hand, added the print referencing intervention taught by the researchers. These teachers would reference print as they were already reading a storybook by:

- Asking questions about print,

- Commenting about print, and

- Tracking their finger along the text while reading.

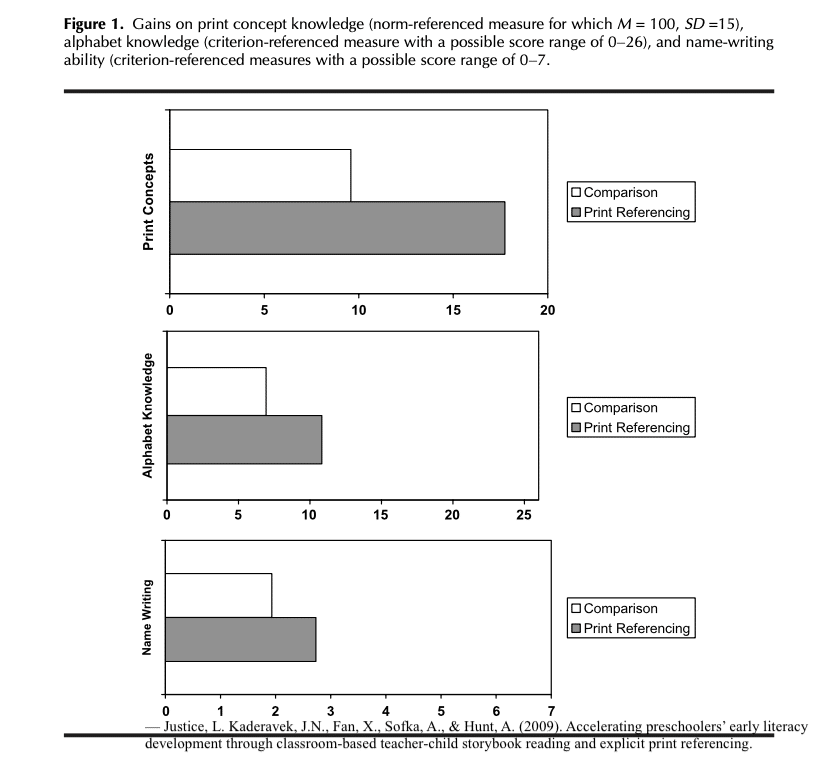

After 30 weeks of these types of storybook experiences, the experimental group outpaced the “business as usual” storybook group in print concepts, alphabet knowledge, and name writing, as demonstrated by the chart below.

“As the results of this study make clear, the present work extends prior findings concerning the positive impacts of print referencing intervention to the preschool classroom as applied by teachers working in a range of program types and as delivered within large- group, classroom-based reading sessions four times weekly. The results show the value-added benefits of teacher reading with a print referencing style to approximate .5 SD on measures of print concepts, alphabet knowledge, and emergent name writing above those we see with exposure to teachers’ typical storybook reading practices. Importantly, children’s performance on such measures is consistently linked to later outcomes on measures of word reading and spelling (National Early Literacy Panel, 2004), suggesting that print referencing may exert positive impacts on children’s future reading performance” (p. 77). (4)

I noticed the power of this storybook print and phoneme referencing approach with our oldest daughter when she was merely two years’ old. I had been occasionally drawing attention to the sounds of words as I read aloud to her. I would also point to some words as I read them.

One day we were together at a store and she pointed to the exit sign. She pointed her finger at the sign and said, “/lllllleeeeeev/” (i.e., “leave”). Did the sign actually say, “leave?” No, she couldn’t read and she didn’t know many letter-sound correspondences at this point.

However, even at just 2 years’ old, she did demonstrate the insight of the alphabetic principle--those funny squiggles represent sounds in meaningful words. She was well on her way!

2. Phoneme Identity Matching Activities. As we see in the activity Build It above, the concept of the alphabetic principle is intertwined with phonemic segmentation ability and letter-sound knowledge. However, very young children sometimes find it difficult to segment even a simple CVC word into its individual phonemes.

Have no fear!

There’s a bridging activity that will pave the way for phoneme segmentation skill and ease of engaging in Build It. Try phoneme identity matching tasks as a simpler version of phoneme segmentation.

As early as 1990 researchers demonstrated that 4 year-olds could be easily taught phoneme identity(5). And Montessori preschool teachers have been teaching this activity for over 100 years! If you need some inspiration or resources for this just google “Montessori sound matching” and you’ll find lots of ideas like these….

Select words that begin with continuant consonants--these are sounds that can be continued or elongated allowing the adult to draw attention to that specific sound in the word. I often choose words that begin with /s/ or /m/ in words such as “sat,” “sit,” “mom,” or “map.” Find or create pictures or objects of a few concrete words that begin with these sounds.

First, teach the children to notice how your first batch of words all begin with the same sound (i.e., “mom,” “match,” “monkey,” “man,” and “moon”). Encourage them to stretch out that first sound in each word as you do: “/mmmmmm/.” You can point to the letter “m” on a letter-sound card and/or at the beginning of word cards, as well, but in this first stage you’ll be mostly aiming to just draw their attention to the phoneme (not the grapheme, or letter).

Next, if the child is getting the hang of it, introduce a second sound and various objects/pictures for it (i.e., /s/ and “sun,” etc.). Follow the same procedure as above to try to get them to attend to the first sound in these words.

Then the fun begins! Create 2 columns--one for each of the 2 contrasting sounds that have been taught so far. Tell the child that you’re going to sort the objects/pictures into one of two categories (i.e., “/mmm/ or /sss/”). Sort the first object in each category for the child and then invite him to begin sorting the objects into the relevant column.If the child makes a mistake, give specific feedback, such as,

“Actually, I hear a /mmmmm/ at the beginning of /mmmmmoon/. But this column is for the /sssss/ sound as in /sssssun/, like this picture of the sun we have here. So where should this picture of the mmmmmoo--n go?”

As the child succeeds at the task, continue to teach more initial phonemes. Then try similar ending phonemes, as in the /t/ in “mat,” “sit,” “bit,” “elephant,” or “minute.” If this activity is going well, fold in the single graphemes into the sorting activity so the child begins to associate the letter “m” with the /m/ sound and so on.

When your students are matching a few phonemes by the beginning of words, they are likely ready to begin Build It. Yeah!!

No need to wait to cover all of the sounds in the alphabet before beginning Build It. (Remember the alphabet doesn’t guide our early reading instruction--the alphabetic principle does. And the best activity for teaching the alphabetic principle is Build It.)

Try replacing the phoneme identity matching activity with Build It now, as Build It will accomplish more early reading developmental gains.

Since many phonological awareness curricula don’t attempt awareness at the phoneme level from the beginning of instruction, you may doubt that your 3, 4, or 5 year-old beginning student will be able to handle this. Let me assure you that many researchers have demonstrated that young kids can handle this type of activity. For instance, Brian Byrne and Ruth Fielding-Barnsley tested this (as have others) and they concluded…

“It is clear that preschool children can be trained to notice the identity of phonemic segments in words. All but one of the subjects scored better than chance on some of the identity tests, and 11 reached criterion on six or more of the eight phonemes. Our data therefore confirm others' observations of the teachability of phonemic awareness

(Content, Kolinsky, Morais, & Bertelson, 1986; Olofsson & Lundberg, 1985)."(6)

3. Build It Activity. The third core activity that I would suggest for the preK tykes is Build It, just as described earlier in this article. When your young charges are ready for Build It, recall that they will be learning:

- the concept of the alphabetic principle,

- phonemic segmentation,

- letter-sound knowledge, and

- early decoding and spelling.

These 3 activities above can be implemented in the same season of schooling, but they also represent a bit of a developmental continuum:

The print-disinterested 2 or 3 year-old can have her awareness to phonemes as well as print heightened by the first activity--Storybook Tracking of Print and Phonemes. This will lay the groundwork for the second activity--Phoneme Identity Matching activities, which most 3 and 4 year-olds should be able to learn.

Finally, with a few days or weeks of phoneme identity, most children will be ready for Build It. This step is so exciting because you are now unlocking for your students how the code works, establishing a firm foundation for later code breaking skill!

Here’s a super short video by Katy Broadbent also explaining the alphabetic principle and offering another bridge activity to help lead to the child understanding the alphabetic principle:

What Is the Difference Between the Alphabetic Principle and Phonemic Awareness?

Because most of us didn’t learn about the terms “alphabetic principle” and “phonemic awareness” in school--even if we were in teacher training programs!--these terms may still be slippery. Let me clear up any confusion you may be having still about the difference between the alphabetic principle and phonemic awareness.

First, the alphabetic principle is an “aha!” or concept about how our written language works. Phonemic awareness, on the other hand, is the perception of individual sounds (phonemes) in words. A child who had received phonemic awareness instruction could have awareness of the phonemes in the word “sat,” for instance, if I speak the word orally only: She could perceive that “cat” is made up of the /c/ /a/ and /t/ sounds.

However, she may still not “get” that those specific phonemes relate to specific graphemes (letters and letter combinations) to help her read the word “cat.”

Why can’t she read the word “cat”? It may be because she doesn’t understand the concept of the alphabetic principle--that sounds in words are represented by letters.

OR, she may not know sufficient letter-sound knowledge in order to decode the spellings in the word “cat.” If she doesn’t recognize the letter “c” as a representation of the sound /c/, how can she read “cat”?

Thus, the concept of the alphabetic principle, phonemic awareness, and letter-sound knowledge (phonics knowledge) work together to help the young learn recognize words. Each sub-skill supports one another, but they are different. We show the beginning reader how all these pieces work together in the activity Build It (and other Reading Simplified activities that we introduce later).

Assessment of the Alphabetic Principle, Phonemic Awareness, & Letter Knowledge

Here are some diagnostic questions you could ask if you’re not sure where your young student’s challenges are coming from:

- Does the child attempt to translate a letter in a word into a sound in a word (even if the attempt is the wrong sound)? If so, then this may be a sign that the alphabetic principle is beginning to be grasped.

- Is the child not able to segment the first sound in a word, such as “sat”? If so, then this is a sign that phonemic awareness is weak.

- Can the child segment the first sound in “sat” but she cannot recall the /s/ when she’s directed to the “s” letter? If so, then she is lacking letter-sound knowledge--for at least the letter “s.” But she’s got at least the beginning stages of phonemic awareness developing!

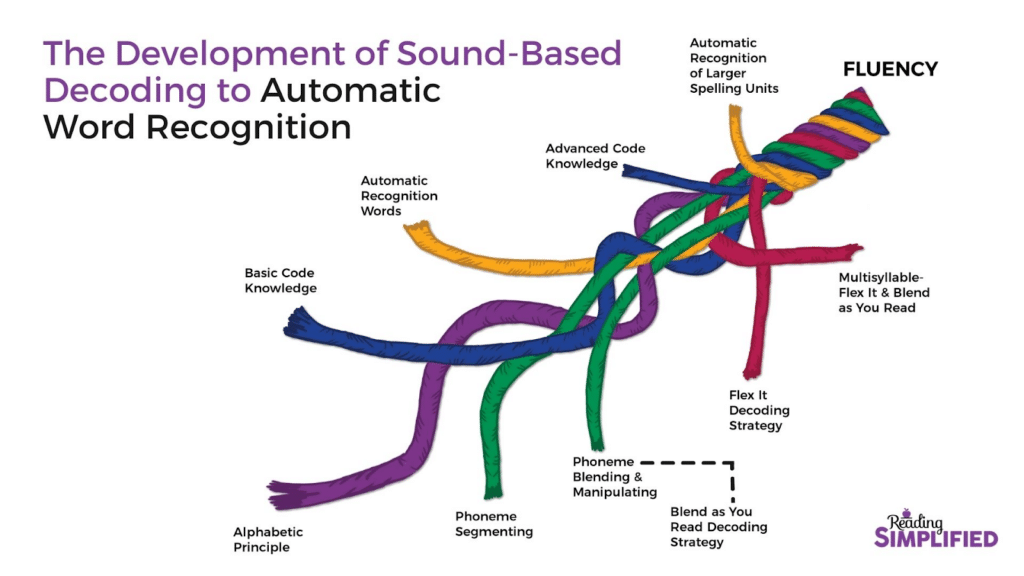

Perhaps the following diagram of the instructional developmental sequence that we follow at Reading Simplified may help. With a hat tip to Hollis Scarborough for popularizing the concept of learning to read as the weaving together of a variety of strands of sub-skills via her so-called Reading Rope(7), here’s our version of the Word Recognition strand that’s more of an instructional sequence:

Notice how the first strand of this developmental process is the alphabetic principle. Voila!

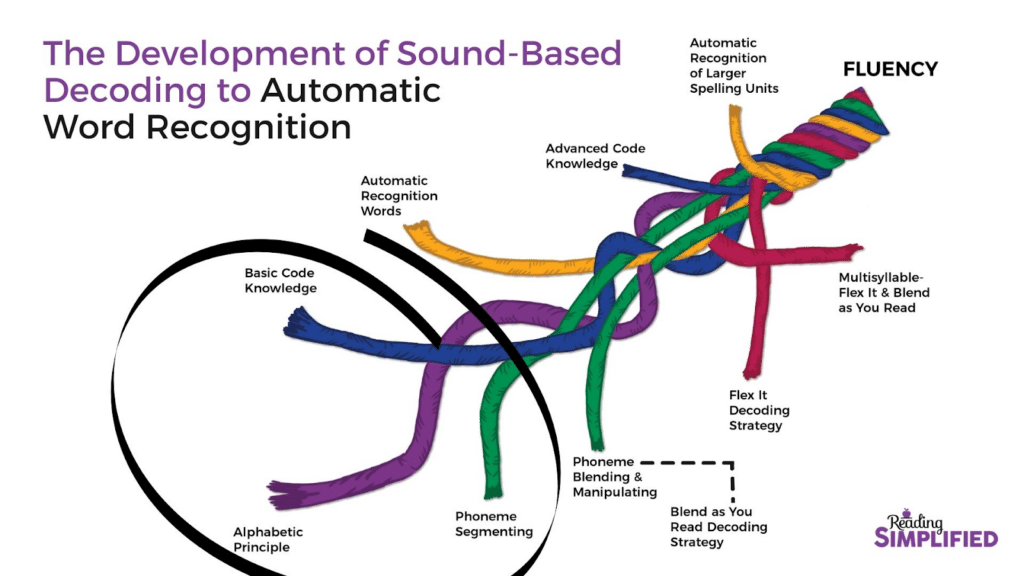

Now see below for the encircled 3 first strands in this instructional model: the alphabetic principle, phoneme segmenting (one form of phonemic awareness) and Basic Code knowledge (as in consonants, short vowels, and consonant digraphs).

They weave together early on for the child who is off to a good start with cracking the code.

Nevertheless, these are only the beginning stages. Grasping the concept of alphabetic principle is important, but it’s not the same thing as being skilled at using or applying the alphabetic principle.

To truly learn how to decode the thousands of words in our language and then recognize them by sight, more reading skills will be necessary. That’s what the rest of the Development of Sound Based Decoding diagram suggests. To become good at decoding, one needs more than just the concept of how the code works.

The developing learner needs more phonemic awareness skills, deeper code knowledge, and automaticity with decoding strategies. These are the skills we specialize on here at Reading Simplified so please plan on coming back for more core activities.

Here's Julie's experience as her Pre K grandson springboarded from Build It to other core Reading Simplified activities...

Watch the full live video replay about the heart of this message from our Facebook live show.

FREE Build it Wordlist

Want to try Build It for yourself?

Leave your first name and email address below to receive your FREE PDF set of letter-sound cards. Then jump right in with Build It.

If you decide to try Build It with a beginning student or early reader, let me know how you get on in the comments below!

References

(1) https://thomas-wolsey.medium.com/the-science-of-reading-says-53b1c7bf30ee

(2) https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1200223.pdf

(3) https://www.researchgate.net/publication/23759692_Accelerating_Preschoolers'_Early_Literacy_Development_Through_Classroom-Based_Teacher-Child_Storybook_Reading_and_Explicit_Print_Referencing

(4) https://www.researchgate.net/publication/23759692_Accelerating_Preschoolers'_Early_Literacy_Development_Through_Classroom-Based_Teacher-Child_Storybook_Reading_and_Explicit_Print_Referencing

(5) https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Acquiring-the-alphabetic-principle-%3A-a-case-for-of-Byrne-Fielding%E2%80%90Barnsley/c0c7ef4ef1054b4fa0b80e7104e291c0c8917361

(6) https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Acquiring-the-alphabetic-principle-%3A-a-case-for-of-Byrne-Fielding%E2%80%90Barnsley/c0c7ef4ef1054b4fa0b80e7104e291c0c8917361

(7) https://institute.aimpa.org/resources/readingrope

excited to begin my next teaching year with some successful strategies to support my kinder students!~ Thanks!

Love the enthusiasm, Jess!! Let us know what successes you have this year!

Thank you for the great information!

May it serve your readers well, Katie!

I love the idea of this-just not sure where to start with build it. What words or letters do you start with?

Great question! The above post offers a free set of letter-sound cards you can use in Build It. We also offer a free Build It word list in this post:

https://readingsimplified.com/teaching-letter-sounds

Once you submit your email address to receive the letter-sound cards and Build It lists, you will notice that we start by building words that start with continuant sounds. Continuant sounds are those that can be sustained easily (like /m/ and /s/). This makes it easier for children to blend the sounds together in words. We hope you enjoy trying out Build It with these resources!

This sounds interesting.

Glad to hear it! Please let us know if you test it out Furlinda…

Where do I get the Free Build it Wordlists?

Hi Kathryn! You can snag a copy here by entering your email address in the pop up box: https://readingsimplified.com/teaching-letter-sounds/