View the Recording

Downloadable Resources

Q&A with Dr. Brady

It would be best to assess phoneme awareness skills in a developmental sequence according to the position of phonemes in syllables.

For beginning phoneme awareness, the progression typically is from awareness of the initial phoneme, to the final phoneme, and then to awareness of the medial vowel phoneme in words that are simple syllables (i.e., C-V-C words).

For advanced or later phoneme awareness, the progression advances to awareness of each of the phonemes in a complex syllable that contains one or two consonant blends, particularly of the internal consonants in consonant blends (e.g., the /l/ and /m/ in ‘clamp’).* The recognition that there is greater difficulty attaining awareness of internal consonants is based on a long-running body of evidence of phoneme awareness errors, as well as of spelling and reading errors, that indicate greater difficulty achieving awareness of consonants in those positions than of phonemes in other syllable positions.

*Note: there are two factors influencing difficulty of awareness of the individual consonants in blends following the vowel. One is related to the challenge of isolating the two consonants in the blend itself, the second stems from the coarticulation of the preceding vowel with the following consonant (i.e., production of the vowel overlaps with the /m/ in ‘clamp’). This is a particular influence for nasal consonants; starting with s-blends is an easier introduction to these kinds of tasks.

Kinds of Measures:

a.) Isolation and identification of phonemes in particular positions.

For beginning phoneme awareness, these skills can be assessed (and taught) by asking students to say what the first sound in a spoken word is, avoiding words that begin with blends. This can be followed by asking the student what the final sound in a one-syllable word is (avoiding words that end in blends), and then by asking students what the middle sound is in words that are CVCs. The cognitive and memory demands of these tasks are fine for kindergarteners and older students. (By following this progression, if a child cannot reliably answer questions on a task, one can stop there, having identified the student’s instructional level and also sparing the child the pressure of questions that seem hard or bewildering.)

b.) Blending and segmentation measures/activities are also useful, again first testing words with simple syllable structures (CV, VC, CVC) and then progressing to words with blends (CCVC, CVCC, CCVCC, CCCVCC).

c.) Likewise, if students have been learning the letter names and letter sounds corresponding with the phonemes they have been targeting in awareness activities (as is recommended), documenting their abilities to build words using the letters/phonemes they have worked with is very worthwhile (See the Build It and Switch It activities in Reading Simplified). Here again, the sequence of development of phoneme awareness provides a guide for the sequence of word building steps. A child’s performance provides information on her/his progress and about their instructional needs.

I have been focusing on research evidence pertaining to phoneme awareness and on the practical implications of that research. Unfortunately, I do not know if there are recent instruments that reflect a better understanding of what has been learned about phoneme awareness development. The ones I am familiar with do not focus just on the key skills described in the previous topic presented above.

I encourage you to apply reasonable standards as you review the options available:

- Do they assess what is described above?

- Do they leave out measures of phonological sensitivity and of oral-only phoneme manipulation tasks?

- Are there multiple sets of words or nonwords for assessing awareness of the different phoneme positions in words? For example, for students who had been needing to work on becoming aware of the initial phoneme, are there extra sets that would enable the instructor to retest them on initial phonemes in new words one or more times to when these students are ready to progress to the final position?

I hope that new instruments will be developed that will be better aligned with current knowledge. In the meantime, one can use tasks from a published battery to test an individual skill for instructional purposes. For example, Robertson and Salter (PAT-2-NU, 2018) have an instrument that includes a number of useful measures of phoneme awareness of the sort described in # 1 above (isolation, segmentation, blending), as well as ones that can be ignored that test phonological sensitivity components (e.g., for segmentation and blending, skip the syllable and word levels); also skip the rhyming and oral deletion tasks). The grapheme knowledge and decoding measures in the PAT-2-NU are good and are a useful complement to the assessment of phoneme awareness. This kind of selective use of subtests of a test battery doesn’t allow one to use the normative scores for the full battery, because that will not have been entirely administered, but can provide very helpful diagnostic information for identifying students’ instructional needs.

On pg. 9 of the IDA Fact Sheet on Phoneme Awareness, there is a section on “When to Provide Instruction on Syllable and Rhyme Structures”. It is not at the pre-K level. Instead, in pre-K one can target alliteration, helping discovery of the first phonemes in spoken words and in time could introduce letter sounds and names that go along with those phonemes. Helping children learn the first sound in their own names and the letter(s) that stands for that sound is rewarding to children.

I do not recommend administering whole batteries that include phonological sensitivity tasks. As research presented in the zoom talk above, acquisition of phonological sensitivity does not facilitate the development of phoneme awareness. Hence, assessing and teaching phonological sensitivity is not a good use of class time.

A further problem pertains to many of the phoneme awareness measures included in assessment batteries that consist of oral-only manipulation tasks (deletion, substitution, addition). For assessment, manipulation tasks are valuable when they include the use of letters. Assessing word building ability of words and nonwords using a set of letters reveals a student’s phoneme awareness development of beginning awareness by using one syllable words without blends and of advanced awareness by using one syllable words with blends. If a student may be relying on memorized recall of real words, then using nonwords will more accurately tap phoneme awareness skills (e.g., instead of using letters to say each of the phonemes in ‘mop’, ask the student to do so for ‘dop’. (Note, as well as using these kinds of tasks for assessment, doing so also is excellent from an instructional point of view, to foster phoneme awareness development both for typical learners and for older struggling readers.)

In the early research on phoneme awareness (e.g., in the 80’s) investigators compared the awareness skills of good readers and of poor readers to determine what each group was capable of doing. The tasks that most strongly distinguished between the two reading groups were the oral manipulation measures (addition, substitution, deletion) particularly for the internal consonants in blends. Ability to perform these activities were thought of as the pinnacle of phoneme awareness and have been included in many phonological awareness batteries over the decades. However, it came to be recognized that the spellings of words (i.e., their orthographic representations) are automatically activated when good readers hear words and that capable readers draw on their reading and spelling skills to perform manipulation tasks, as well as on their phoneme awareness prowess. Hence, their superior performance on these measures is largely a consequence of their reading skills, not a necessary precursor for becoming skilled readers. Yet, unfortunately, graphic representations and popular programs to enhance the development of phoneme awareness have been focusing on the use of phoneme manipulation tasks without letters for instruction and assessment – and this has become an ingrained incorrect belief about phoneme awareness development.

The Matthew Effect: The rich get richer and the poor get poorer. In this context, does doing the phoneme awareness activities without letters benefit the strong readers, yet not help the readers who have not yet mastered all levels of phoneme awareness?

I don’t know that it helps the stronger readers. They may get better at the mental gymnastics to do such tasks, but there isn’t evidence that this has a causal benefit for their reading skills. Given that reading and spelling skills are tapped to do these tasks, the students with those skills probably already have acquired the latter, more advanced phoneme awareness skills and will not improve their reading skills by doing manipulation tasks without letters. At the same time, for those students who need to refine and further develop their phoneme awareness, doing these tasks without letters makes it much harder: the students instead would be helped by systematic lessons that include letters (adding and removing them) to support awareness of phonemes in the different positions in one-syllable words.

No, but I have discussed the issues with Dr. Kilpatrick at some length, and he has read my articles on the topic in The Reading League Journal. My assessment of the research, including recent meta-analyses of relevant research, is that the evidence is quite strong both for the merit of focusing awareness instruction on phonemes and on linking those awareness activities with letters. You are correct that Kilpatrick takes a different stance on these issues both in Essentials and in his phonological awareness program, Equipped for Reading Success. This past year on Timothy Shanahan’s website there was a blog titled “RIP to Advanced Phoneme Awareness” (https://www.shanahanonliteracy.com/blog/rip-to-advanced-phonemic-awareness#sthash.of9wIDQk.uIJabZpf.dpbs) referring to David Kilpatrick’s use of the term to specify oral manipulation tasks. In that blog, Kilpatrick acknowledges that there is no research at this time that validates the use of his type of phoneme awareness manipulation tasks to build phoneme awareness and reading skills.

Here you are:

Rehfeld, D., Kirkpatrick, M., O’Guinn, N. & Renbarger, R. (2022). A meta-analysis of phonemic awareness instruction to children suspected of having a reading disability. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 53, 1177-1201.

Conclusions: The present meta-analysis confirms that phonemic awareness instruction can be effective with children of varying ages and that significant gains can be observed on the key outcome measures of segmentation and blending. Graphemes should be incorporated into phonemic awareness instruction, and future studies need to provide information on dosage beyond just the length and frequency of sessions to clarify which aspects of these interventions are most efficient.

Stelaga, M., Kearns, D., & Bayer, N. (July, 2022). Is phonological awareness only instruction helpful for reading/: A Meta Analysis. Presentation at the Conference for the Scientific Study of Reading, Newport Beach, California. Paper in progress.

Conclusions: PA-only instruction improves reading-related skills more than comparison instruction that does not teach PA, but it is less effective than reading-related instruction with PA that includes letters.

Yes, in fact, oral only is fine when doing isolation/identification tasks (e.g., What is the last sound in ‘pig’?), blending (What word does /b/ /a/ /t/ make?) and segmentation tasks (e.g., Tell me each sound in ‘spy’.) The tasks not appropriate for oral only are the manipulation tasks (addition, substitution, deletion) that place heavier demands on phonological memory and have more cognitive steps to follow. On the other hand, manipulation tasks incorporating letters offset the memory and cognitive demands while bolstering knowledge of the phonemes in spoken words, including both the simpler kinds of syllables (CV, VC, CVC), and later, of the harder syllable patterns with internal consonants in blends (CCVC, CVCC, CCVCC, CCCVCC). I want to note that these recommendations apply to all learners, differentiating as needed for students at different levels of awareness.

This was posted by Tiffany Peltier here on her website Understanding the Science of Reading.

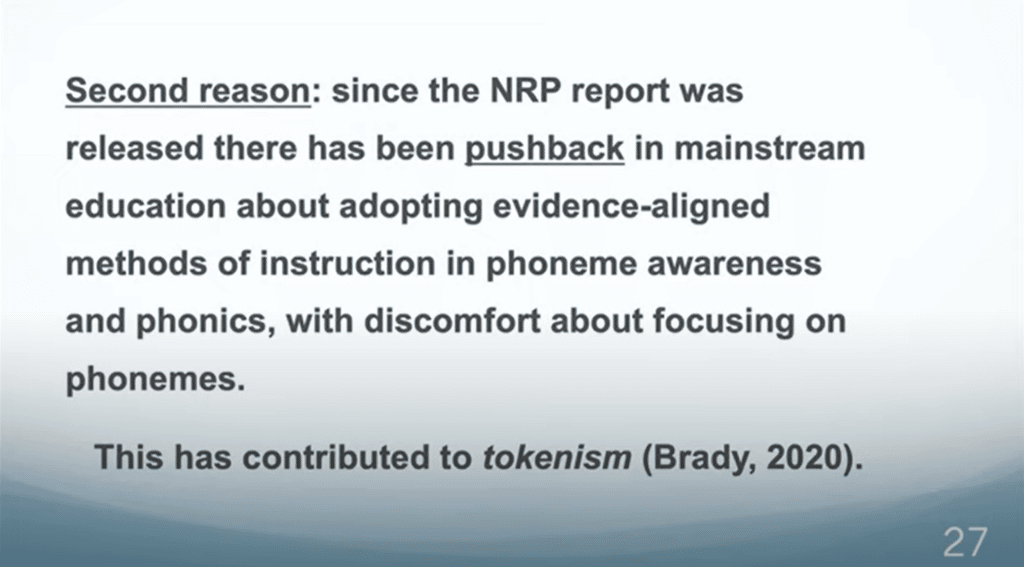

In slide 27 (see the box below), I was commenting on why there is so much instructional focus on phonological sensitivity in commonly used programs.

To unpack this: Many in education were uncomfortable after the NRP was published with now being encouraged to focus on phonemes and phonics when up to now they had been adherents of whole language and the three cueing approaches. The pushback to ‘the science of reading’ has been illustrated by the design/adoption of programs concentrating extensively on phonological sensitivity lessons without letters and then when the program gets to the phoneme level only doing it in a limited “token” amount. This has left too many students who lack fully-developed phoneme awareness–often of the internal consonants in syllables with blends.

This program was developed in New Zealand. It has good features, but is for children in New Zealand whose accent is quite different from American English speakers – including common dialects in America. The vowels sound particularly different – for example, when ‘bat’ is pronounced, it sounds more like ‘bet’ to me. Consequently, I don’t think this particular program would work for American students, but the idea has promise.

No, just summary statements about the program. However, Gillon has provided information online for two programs – the first is a program she wrote up in 2008, The Gillon Phonological Awareness Training Programme, the second is about the program used in the study I cited (https://www.betterstartapproach.com/gillon-pat-resources). They are very similar. One change I would suggest would be to drop the beginning rhyming activities and to start with the phoneme activities that make up the bulk of the program. Because she is from New Zealand, you’ll see some spelling differences and because of differences in that dialect, may need to change items in tasks so they work for speakers of American English.

Spelling and reading skills are highly correlated across a broad range of ages–though not identical, they have much in common. For beginning readers, phoneme awareness and letter sound knowledge are key elements of both spelling and reading development. As reading skills become more established, the demands of spelling in English increase (with multiple languages contributing to spelling patterns and because morphemes are generally preserved in spellings). Spelling skills usually lag to varying degrees behind word reading ability for the majority of readers. This reflects the differences between recognition and recall – it is generally easier to be able to read words than to remember how to spell words.

Phonological abilities (phoneme awareness, phonological working memory, speech perception) contribute to individual differences in both spelling and reading–with spelling being more strongly impacted than reading. In turn, dyslexic and other struggling readers typically have spelling weaknesses that can persist long after reading skills have advanced. Although there are other factors that influence spelling abilities, such as dysgraphia, the use of spelling performance to identify phoneme awareness difficulties has long been recognized as useful for diagnostic teaching purposes. As mentioned in the talk, if a speech sound is missing from a written word, this is a clue that the student may not have acquired as much phoneme awareness as necessary (e.g., bd for bed, bed for bend, bend for blend). If, on the other hand, the student writes words that are phonologically correct, though not the conventional spelling (e.g., buc for book) that does not suggest a phoneme awareness problem.

If the goal is to test mastery of different stages of phoneme awareness for instructional purposes, I think it would be desirable to test initial sound accuracy first and followed by fluency with words that do not begin with a blend, and then later, when the child has demonstrated mastery of beginning phoneme awareness, move into instruction and assessment that taps awareness of the individual phonemes in blends.

It is well documented that linking phonemes with letters (letter names and sounds) facilitates development both of phoneme awareness and of foundation code skills. If the student is guided to discover the first phoneme in a spoken word–let’s say the /m/ at the beginning of ‘mouse’ and the teacher then shows the child that the letter ‘m’ stands for that sound, the child starts making these links (and begins to understand the alphabetic principle–that is, how the alphabet works). Integration of these skills is superior to teaching phoneme awareness as a separate unit from phonics. Linking with handwriting is also very beneficial.

Once letters have been introduced, this doesn’t mean that one is done with the focus on phoneme awareness. We talked about first targeting awareness of a small set of phonemes/ letters (for example, 6-7 consonants and 1-2 short vowels) that can lead to reading and writing a set of words. Awareness of each of the phonemes needs to be practiced with multiple words (e.g., a variety of words that begin with /m/). And those phonemes need to be linked with letters multiple times. When the educator shifts from targeting initial phonemes to the final position, the child now can be asked what’s the final sound in a word (e.g., /him/), discovering the /m/ again in this position. After this set of phonemes/graphemes is mastered, others are added in and the back and forth between phoneme awareness and early phonics continues, etc. In short, instruction on phoneme awareness and on letter names/sounds should be intertwined, going back and forth from one to the other to reinforce the knowledge and the automaticity of each area of knowledge and building the links between them. In the National Reading Panel Report, phoneme awareness and phonics were covered in the same chapter as related elements of “alphabetics”.

Are “close in time” lessons that may have a minute or three of oral only PA moving quickly into another component of a lesson that connects those phonemes to letters o.k.? YES

Or are we really saying integrate PA and letters all the time? NO

Here’s a video clip of Marnie Ginsberg doing “Build It” with a young child that illustrates the emphasis on phoneme awareness in a task that uses letters as well.

I have found that going from awareness of a phoneme to the sound of the letter that stands for that sound works well, facilitating realization of the alphabetic principle. (If a child has already learned letter names, though, this is not a problem.) What has been found is that as a child goes forward with learning/remembering the letter-sound pairs, knowledge of the letter names boosts recall of the letter sound (and vice versa) when decoding because many letter names begin with the letter sound and some others have it as the final speech sound. In short, I don’t think one needs to avoid letter names, but should be clear about these two different aspects of a letter. Also see #17.

In order to help the student, one has to determine why the student “can’t get them on paper”? Can the student say each sound as she/he taps out the word? Is the student in fact tapping the correct number of phonemes for words of different lengths (2 vs 3 vs 4 phonemes)? How does this student do on other phoneme awareness measures such as first sound isolation, etc.? How solid is the student’s letter knowledge for letter names, letter sounds, and handwriting? Does she/he have difficulty with letter formation?

By identifying the source(s) of the difficulties, one can then develop a plan for addressing those gaps or weaknesses.

Children can be helped by learning about the structure of syllables when they are starting to write one syllable words. That is, they can be told that every syllable has to have a vowel. In addition, they can learn that syllables can have consonants before and/or after the vowel, but these are not mandatory. The teacher can show examples: of one-syllable words: I, me, am, bed, step (adding other more complex examples as students are ready). This instruction also complements teaching syllable types (closed, open, silent e, etc.) When students are ready for two- and three-syllable words, learning syllable division strategies to facilitate reading each of the syllables is constructive. However, in my experience, syllable awareness activities such as counting or segmenting have not been needed for any of the above.

It is commonly found that older poor readers have not fully mastered phoneme awareness, impeding their reading and spelling skills. A first step would be to assess the student’s extent of phoneme awareness: one student may only have awareness of the initial and final phonemes in words (e.g., not being able to identify the medial vowel when given CVC words) in which case that would be the level of phoneme awareness to help the student next master; another student may have awareness of the initial, final and medial speech sounds in CVC words, but make errors on words that are more complex syllables (e.g., saying /pl/ /a/ /n/ when asked to say each of the speech sounds in ‘plan’). You also may see evidence of this phoneme awareness profile on a manipulation task with letters (e.g., when asked to pull down the letters for ‘plan’, the student just pulls down p-a-n.) For this second hypothetical case, the student would be ready for support building his/her phoneme awareness to the later or more advanced level. There is not research showing that deletion and other manipulation skills without letters are essential. (See # 7.)

No, it isn’t ever too late. Phoneme awareness can be developed at any age. If you find evidence of phoneme awareness deficits, this can be corrected with the kinds of activities discussed earlier.

Yes, if needed. If you have assessed the student’s word building skills and they are having trouble in this area, then investigate why. Does the student have gaps in phoneme awareness abilities, in letter-sound knowledge, and/or in mastery of spelling patterns? If so, focus on the needed areas to build word-level spelling and reading skills. Re-check periodically to confirm when the activities can progress to more advanced phoneme awareness and orthographic skills. Integrating this instruction with other skills also would be beneficial, for example, writing activities, practice reading connected text at their decoding level, and comprehension of what they have read.