[8 Minute Read]

Want your students to read and spell efficiently? Cut the fluff.

Yes, we’re borrowing this phrase from the longer Archerism, “Teach the stuff and cut the fluff.”

If you haven’t heard of Anita Archer or it’s been a while since you’ve listened to her speak, this is worth your time!

It had been a while for me – and hearing her again reminded me just how great she is at delivering clear, research-based guidance for reading instruction.

In that spirit, let me use one of her quotes to:

- deliver a simple message,

- connect it with insights from other leading researchers on efficient reading instruction, and

- offer a streamlined solution that actually helps students learn to read faster.

Teach the Stuff, Doesn’t Mean Teach Everything

Too many reading programs overload students with activities that don’t directly build fluent word recognition.

However, research is clear – to become fluent readers, students need repeated, successful practice blending sounds into words, segmenting words into sounds, and making connections between spelling and meaning.

The most effective and efficient instruction does exactly that, without distractions.

Both Dr. Anita Archer and Dr. Mark Seidenberg have raised important concerns about how the science of reading is sometimes applied in classrooms or taught to professionals.

While both fully support evidence-based reading instruction, they caution against overloading students – and even teachers – with unnecessary details that can slow progress.

In a Reading Road Trip podcast, Archer shared her worry that some educators are increasing students’ cognitive load by teaching concepts that aren’t essential for learning to read.

She gave the example of a teacher insisting that students needed to know the term diphthong when learning the /oi/ sound, pointing out that she had read proficiently for decades before encountering the word!

Her takeaway? Teach what students need to know and “cut the fluff”:

“One of the things I’m concerned about a little bit with the science of reading — so many of you have taken classes — LETRS classes, AIMS classes, CORE classes, other classes on the science of reading…

And that was to be certain that we had the best understanding of all of the aspects of language possible involved in reading. But it didn’t mean that we had to teach all of that to our students.

And what I’m concerned about is that sometimes we are increasing the cognitive load that students have — that may actually slow the acquisition of reading — and then get them reading…

Let’s say — so this one was recent — someone said about an intervention, “Well, they’re learning the ‘oi’ and ‘oy,’ and you don’t say that it is a diphthong?”

And I said, “No, we don’t mention that it’s a diphthong. We mention that the sound is /oi/. ‘Oi’—/oi/, ‘oy’—/oi/. And they master /oi/, and then they’re able to read words with /oi/.”

I said to the person, “Now, when did you learn the term ‘diphthong’?”

“Well, I learned it last fall when I took this class. I learned ‘diphthong.’”

I said, “Now, how old are you?”

She said, “Sixty-four.”

I said, “Oh, so you had a good 50 years that you were able to read quite proficiently — not recognizing it was a diphthong.”

That’s just an example of the care we have to take. Because they don’t necessarily need to know what [we] need to know.

They need to know letter sounds. They need to know how to do continuous blending and sound out words without stopping between the sounds. They need to know how to segment so that they can spell.

But sometimes, I see where people have listed all the possible variant sounds for “a” — all the different graphemes that could be used. And I had to look up one on a list, at the bottom of the list, because I couldn’t come up with any words that had that sound in it.

Now, I think that’s the test. If I can’t generate any words, then perhaps — maybe — we could, like, skip it! And when they’re in college, they could see that word and say, “Oh, there’s another way to say that sound. Isn’t that fascinating?”

But there is — I’m quite serious about this — we have to be careful that we don’t adopt methods or content they don’t need to learn and increase the actual amount of cognitive load that is occurring.

So that’s just my curiosity right now. And so — teach the stuff and cut the fluff — sort of covers that.”

The Goal of Reading Instruction: Escape Velocity

Similarly, in his talk at the Yale Child Center Summit, Dr. Mark Seidenberg challenged the assumption that breaking reading into too many isolated components is always beneficial because it interferes with the goal of achieving “escape velocity” – the point where they can learn from activities on their own.

(That’s part of Share’s Self Teaching Theory. Learn more about EXplicit but not EXhaustive Phonics Instruction here.)

Like Archer, one of his key concerns is the “failure to distinguish what the teacher needs to know vs. what the reader needs to know.”

He also warns against the idea that “you can’t have too much of a good thing” when it comes to explicit instruction, arguing that a slow, overly structured approach can lead to low expectations about student progress.

His advice?

The clock is ticking. The goal is to get in, get out, move on.

Dr. Mark Seidenberg Tweet

– Especially for code-based instruction.

In his talk for The Accelerate Literacy Summit, Seidenberg shared,

“So we’re talking about cracking the code, not having to teach the whole thing, achieving escape velocity to allow the kid to kind of start learning from other kinds of experiences. That takes a lot less time than what we’re currently doing. I’m talking about kindergarten and first grade. It’s easier instruction to deliver because there’s less of it. It doesn’t require extensive training in the components of reading. The teacher doesn’t have to be a linguist or cognitive scientist. Sometimes I think we’re really asking teachers to become experts in these fields where people have done a lot of research. That isn’t that closely tied to the problem of “What am I going to teach?” and “What’s going to be effective and efficient?“

More recently, in his talk with Maryellen MacDonald at Planet World Eyes on Reading: What’s Next in the Science of Reading?, Seidenberg reiterated some of these points, expressing that it’s time to recalibrate this level of explicit instruction in foundational skills because there are consequences to components that are learned more implicitly if we take too structured of an approach with all language components.

“The way structured literacy is being implemented reminds me of that idea of just adding one note at a time to build up the structure. So what’s happened? Well, if you treat everyone like they might be dyslexic, you get an intensive, slow, incremental approach to instruction with no stone left unturned. In practice, what it’s meant is a barrage of explicit instruction.”

@markseidenberg Tweet

Like Archer, Seidenberg shares information that seems irrelevant for students learning to read.

Both Archer and Seidenberg highlight an important reality—effective reading instruction isn’t about teaching everything adults know about literacy, even when it excites us—it’s about teaching what helps kids read, quickly and efficiently.

This aligns with Cognitive Load Theory (CLT), which proposes that human working memory has limited capacity and can be easily overwhelmed when learning new, complex information.

What Students Really Need for Efficient Reading

Dr. Devin Kearns likewise emphasizes that students need strategies that actually help them quickly and efficiently read big words.

Overloading them with unnecessary terminology or rigid syllable division rules can backfire, even if those tools are helpful to some.

Kearns suggests,

- Reduce Cognitive Load – Avoid teaching unnecessary meta-knowledge, such as excessive syllable types or complex division rules, which can slow students down instead of helping them.

- Use Familiar Words – Ensure students practice decoding with words they have heard before to support meaning-making and retrieval.

- Teach Practical Syllable Awareness – Instead of rigid syllable division rules, students should understand that every syllable has at least one vowel and should develop flexibility in recognizing syllables within words.

- Leverage Morphological Awareness – Teaching morphemes (familiar bases, compounds, prefixes, suffixes, and roots) significantly improves word reading and vocabulary knowledge.

- Encourage Efficient Decoding Strategies – He suggests students should underline vowel teams if they have learned them and focus on patterns that actually aid reading, rather than memorizing arbitrary syllable rules.

This builds on what Anita Archer emphasizes about foundational skills like segmenting and continuous blending, ensuring students focus on decoding words efficiently rather than memorizing terminology or cumbersome strategies.

There are a lot of strategies that LOOK fun and engaging but have minimal scientific backing, so be careful what you’re choosing and hold some things loosely.

Keep Reading Instruction Simple, Keep it Effective

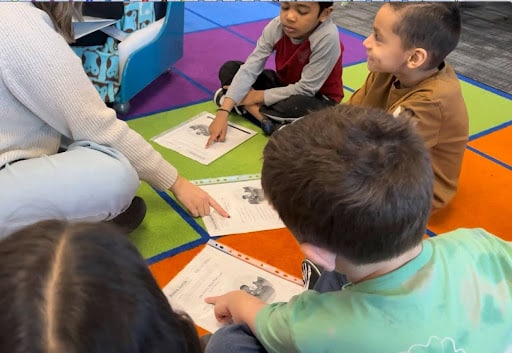

Want a simple, research-based, and effective way to teach reading without overwhelming students with jargon?

Reading Simplified focuses on the essentials:

- Letter sounds

- Continuous blending

- Segmenting

- Flexible word analysis

Students develop these skills through just a few powerful activities:

- Switch It

- Sort It

- Read It

- Write It

- Plus their multisyllable versions

The beauty of this?

Students develop phonemic awareness, decoding, and spelling—simultaneously.

These engaging, evidence-based activities make every instructional minute count.

Want to impact vocabulary instruction by expanding on semantics, syntax, multiple meanings, cognates, and morphology?

Check out our Voluminous Vocabulary Routine and the work of Dr. Freddy Hiebert—designed to integrate semantics, syntax, multiple meanings, cognates, and morphology with ease.

The best reading instruction is lean and impactful.

Ditch the busy work.

Focus on core skills at the right time.

And use strategies that do double—or even triple—duty! (Have you heard about Flex It and Write & Say?)

Your Turn!

What labels, teacher knowledge, or instructional baggage do you need to let go of to make your instruction quick and effective?