Much of educational research is bunk.

There I said it.

And, yes, I'm a researcher. 😮

BUT...

Some educational research transcends fads, small sample sizes, and over-drawn conclusions.

Some educational research truly disseminates insightful conclusions based on multiple, diverse, long-ranging studies.

John Hattie's research is one such shining example. Across many years, Hattie has demonstrated, through meta-analytic studies, which educational intervention make a difference.

And which ones really don't.

{To watch the video where I explain the 4 types of reading errors hit play below, or read on for a detailed overview}

Giving Feedback Is a Really Big Deal

Hattie examined about 200 different types of educational levers, such as low class size, parental involvement, teacher expectations. Then he stacked ranked them according to effect size, a statistical measure of impact.

Effect sizes of 0.4 and above are the ones to pay attention to. They really move the needle.

Matching students to their learning style, for instance, ranks at about the 150th most influential lever, with an effect size of just 0.23.

Giving feedback, however, is in the Top 10, with an effect size of 0.73. Well above the .4 cut-off mark.

Through my work with students and teachers, I, too, have found giving timely, specific feedback to word-level reading errors is especially important to accelerating reading achievement.

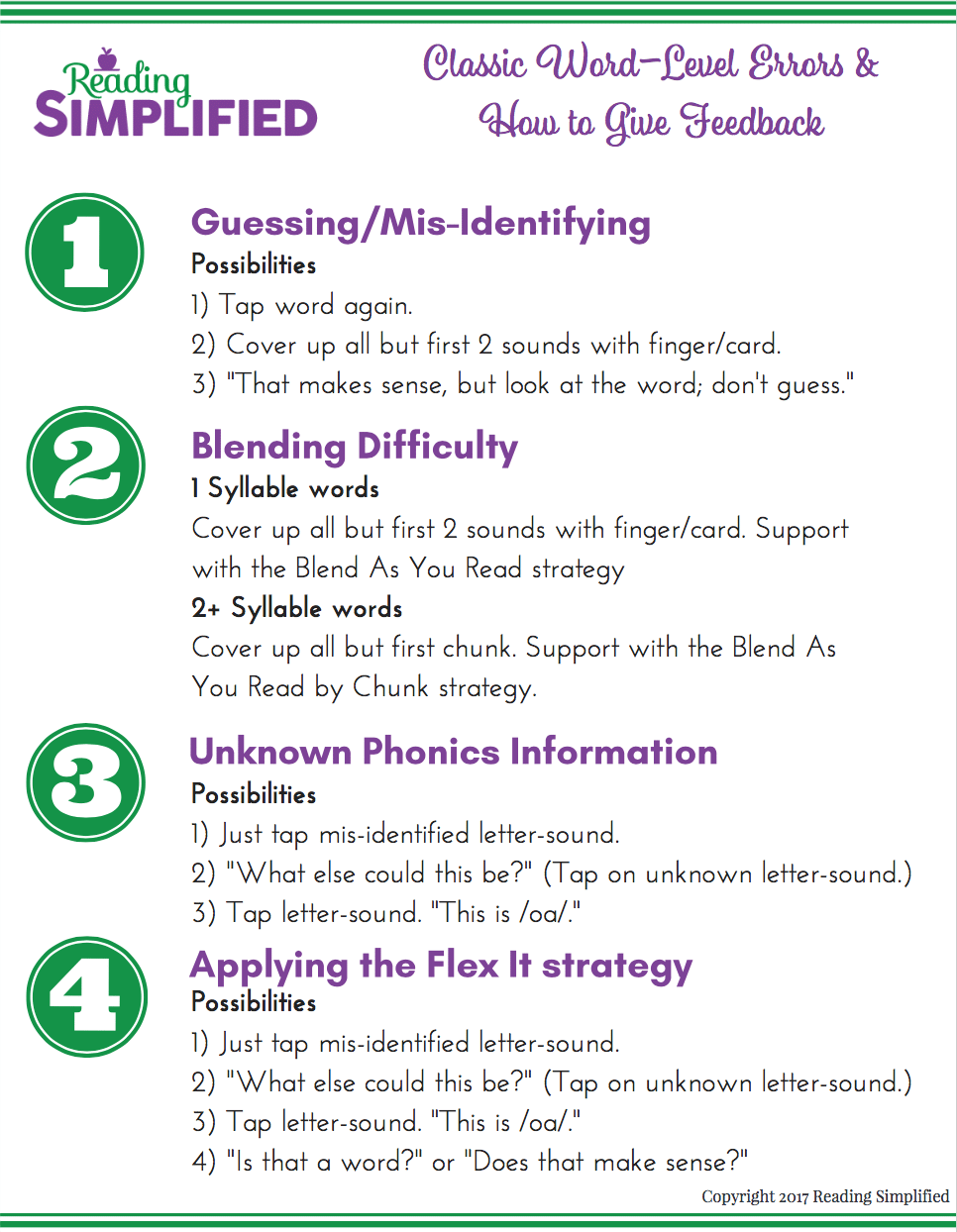

4 Classic Types of Word-Level Errors And How to Give Feedback

Even though feedback may feel like an enormous topic, there are actually just 4 classic errors that most beginning and struggling readers make in their word-reading errors.

Sweet! That's manageable!

Once you know 1) what the classic error types are AND 2) how to respond to them, coaching readers during Guided Reading will be a lot easier. Shall we review them together?

These are the 4 classic types of word-level errors that beginning and struggling readers make:

- Guessing or Total Whiffs

- Blending Difficulties

- Unknown Phonics Information

- Applying the Flex It strategy

(And, stay tuned below to watch a 1st grader reading Frog and Toad make all of these errors and how a teacher helps correct him.)

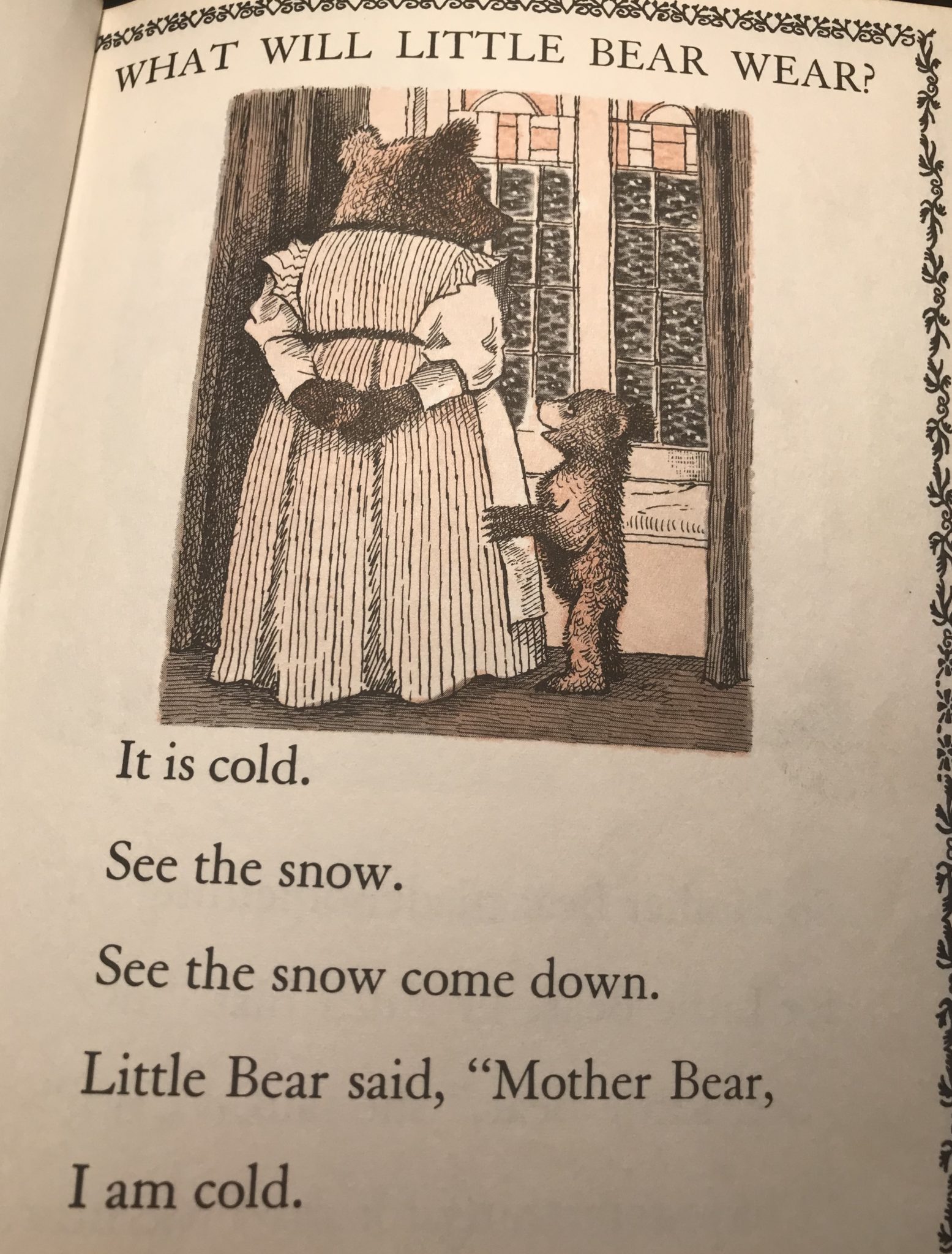

First error up at bat: the Guess or the Total Whiff. The student may be making a guess based on the first letter and/or context alone. For instance, the text reads,

I want something to put on.

But the child attempts,

I want something to wear.

A logical attempt based on context, indeed.

However, it also belies significantly less attention to the print on the page than is needed.

Similarly, a child might read the word "of" and "from," simply because the wires for those 2 high-frequency words got crossed briefly.

#1 Giving Feedback for Guessing Errors

For either type of error, there are a few ways to support the reader:

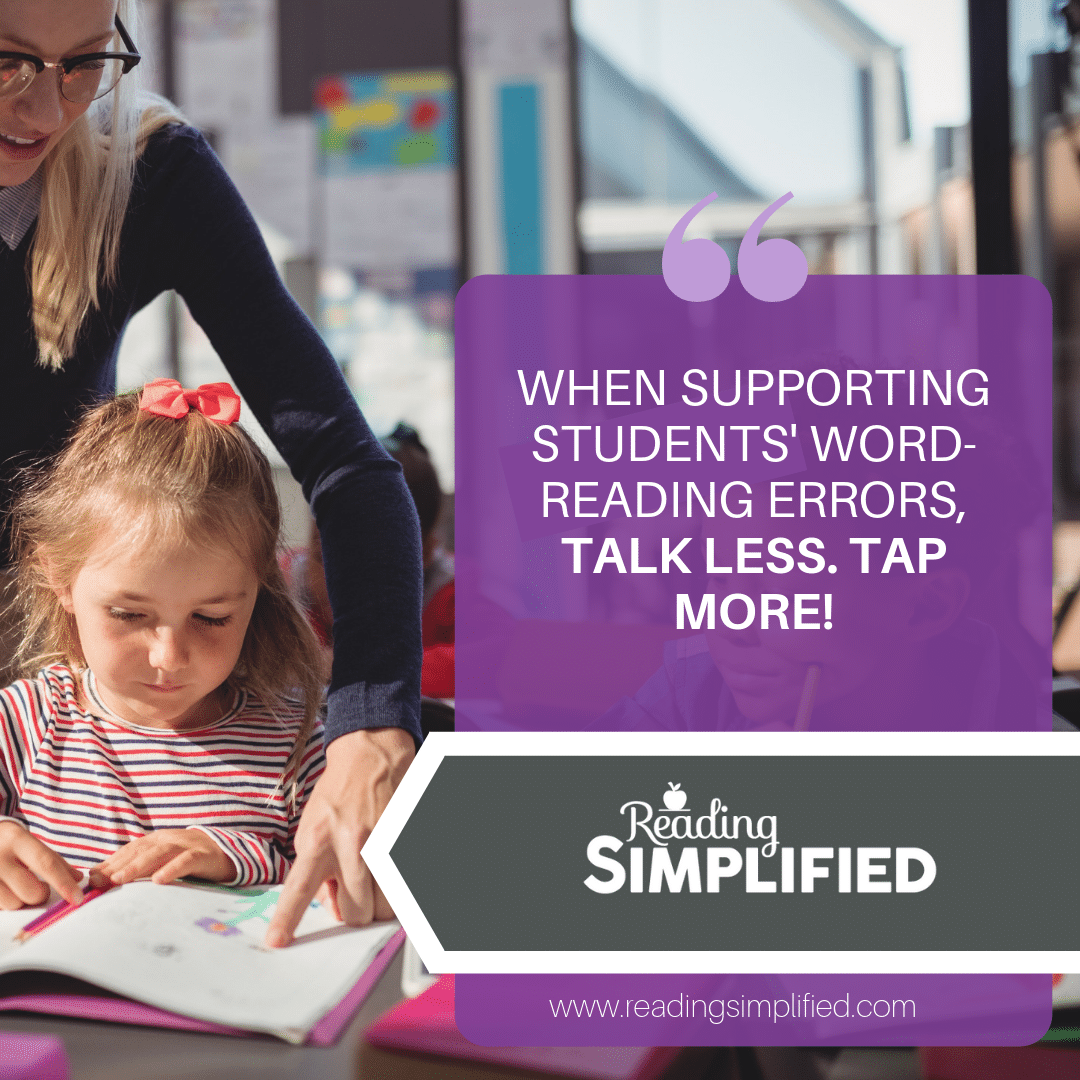

- Tap the word again with the pencil point.

(This is the least amount of feedback and one I often aim to attain. The non-verbal cue of the lone pencil tap gives the child the opportunity to do the work himself AND it prevents him from needing to process another stream of language beyond his own deducing of the word.) - Cover up all but the first 2 sound with a small card or fingertip.

(This is another non-verbal cue that helps zero in the child's eyes to the 2 letter-sounds she should be studying in order to utilize the Blend As You Read decoding strategy.) - Tell the child, "That makes sense, but look at the word; don't guess."

(This cue is important when we want to validate the reader's attempt at meaning-making. However, it also signals to her that reading is first about looking at the print on the page.)

One of these 3 types of feedback often gets the student back into the game. Many times, one of these cues is all that is needed for him to read the word correctly.

However, often, these types of feedback are just the entre into one of the other errors, so further coaching is likely.

For instance, the student probably guessed somewhat wildly because she knew that she didn't recognize the phonics string in front of her. Thus, our next step would be to give the feedback below that's suggested for unknown phonics information.

#2 Giving Feedback for Blending Difficulties

Whether 5 or 15, students make blending errors all the time.

They look at "black" and say "back."

The word is "improbable" and they say,"impossible."

They read /s/ /u/ /n/ but say "nut." LOL.

We can recognize them as blending problems because the child knows the phonics info--he just didn't access it or put it into play.

With this second classic error type, I recommend the blending strategy Blend As You Read. Learn all about it and how to avoid common blending pitfalls here.

The Blend As You Read decoding strategy encourages students to put the sounds together as they go, from the very beginning of attempting the word.

Rather than trying the Sound, Sound, Sound, Word method like this:

/s/ /p/ /o/ /t/.

The student using Blend As You Read says:

/ssssp/

/sssspo---/

"spot!"

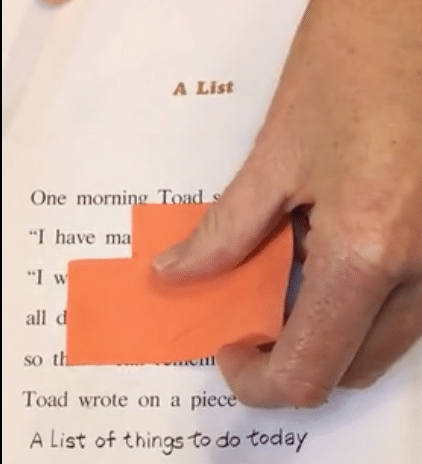

We can give not-so-subtle non-verbal cues to trigger this strategy by covering up all but the first 2 letter-sounds (in the case of 1 syllable words) or the first chunk (in the case of multisyllable words).

I find a little notched card is helpful for helping young eyes to zero in on the first vital sounds or chunk (syllable). (See image above)

In this example, the teacher helps him first blend the “ma” in “many.” Then he reads /men/.

Finally, she covers up the “man,” revealing only the “y.”

And the first grader decodes “many” accurately and forges ahead.

#3 Giving Feedback for Unknown Phonics Information

The English language has over 240 graphemes, or letter-sound combinations; some as easy to learn as “s,” and some as odd as “gn.”

Given that there’s so much phonics information to learn, we can expect errors of phonics information to come up A. Lot.

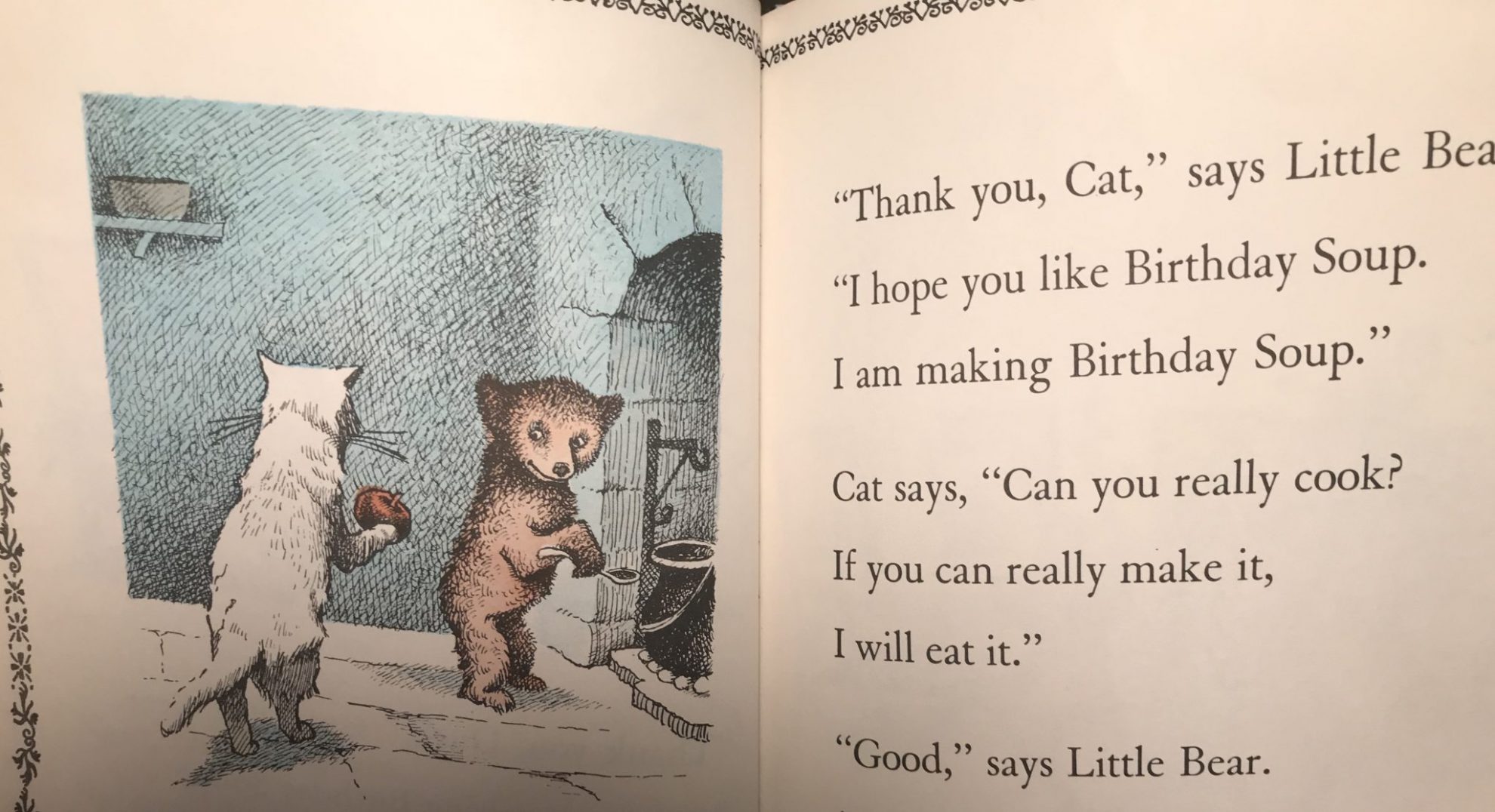

For example, what if the young reader comes to the “ou” in “Soup” (above) and attempts, “/sowp/?”

Here are some quick ways to give feedback to this type of phonics error:

- Just tap mis-identified letter-sound (or likely unknown sound) with a pencil.

(This is a similar tactic to Error #1. No talking. Just a non-verbal cue to draw her attention to the tricky aspect of the word.) - Or, you could ask, “What else could this be?”

(as you tap the unknown letter-sound). - Or, for the most support, tap or underline the letter-sound and tell the student the missing phonics information.

”Yes, this is /ow/ in other words, but in a few words, this is /oo/.”

(What’s critical about this option is that even though the teacher is giving some of the information about the word to the student, the student still needs to do the work of blending the sounds to make a word that he knows.

He is not just working on the one word “soup” with this interaction.

He is:

a) learning a new /oo/ spelling,

b) practicing the Blend As You Read strategy, and

c) generating skill and information to put to use in the future, for future word attack.)

#4 Giving Feedback for Applying the Flex It Decoding Strategy

Finally, many times kids have sufficient blending skill and phonics knowledge, but they still mis-read an unknown word.

For instance, a reader may attempt the word "Bear" as /beer/ but know it's not correct.

She may have studied that "ea" is sometimes /ay/ as in "great" but she doesn't put it into play in this word.

And yet she looks stuck and doesn't make another attempt.

We want her to develop her own word-attack ability, so we coach her to develop the Flex It strategy. The Flex It strategy is the 2nd decoding strategy to learn after Blend As You Read.

When using the Flex It strategy, the student simply tries one sound in a word. If it doesn't make a word or make a word that fits the context, then she tries another sound.

In other words, she's flexing the sounds in her mind, on her own, until she arrives at a word that fits the context of the sentence.

The Flex It strategy is a decoding technique that will serve her the rest of her life, no matter how advanced her reading becomes.

Take this word, "syzygy" for example.

How did you attempt to say it?

/siz ie gee/?

or

/size i gee/?

Did you have to Flex the vowel sounds to determine which one might sound more like a word?

Dictionary.com tells me the first attempt above is correct. (Curious about that funky word? Learn about "syzygy" here.)

But back to our young reader...

When she attempts "bear" as /beer/, what can we do? Many of the same things we've tried before:

- Tap the mis-identified letter-sound with the pencil point. That will more quickly reveal to her where she needs to Flex the sounds.

- Tap the letter-sound and say, "What else could this be?"

- Tap the letter-sound and give her the missing phonics info (only).

- Ask her, "Is that a word?" or "Does that make sense?"

Pushing her to use context is especially relevant when she seems unconcerned that she just read something that's not a word or that doesn't make any sense. Thus, that's when we apply feedback type 4 in the list immediately above.

When she's perplexed and stops, she knows she's got a meaning-making problem. At these times, any of the first 3 types of feedback immediately above would be appropriate.

A First Grader Makes These Classic Errors But Is Coached Through Them

Watch the 1st grader reading Frog and Toad above. Notice his errors....

Did you see the 4 classic word-level types in action?

Also, the teacher (me !!) made at least 1 mistake, so I hope that frees someone watching from the need to be perfect. 😉

Let the Student Do the Work

While we're on the subject of word-level errors and how to give feedback that makes the biggest change, I have a couple of other vital tips.

Let the student do the work of reading hard words. That's a biggie.

Don't talk too much. Let the reader read. And think.

Don't give too many words away.

Don't reduce the text difficulty so that the student doesn't make any errors.

It's through errors--with specific, targeted feedback--that readers are made.

Each word-reading attempt isn't simply an attempt at that word alone.

No, no, no, my dear friend.

A lot more is happening with each error and correction.

When the teacher gives the least amount of information necessary for the student to figure the word out on his own, then the student has more confidence and more abilities to attack unknown words than he did when he began.

[Yes, when a child is discouraged, or tired, or the word is impossibly hard, just give the word to the child. But these give-aways are usually the exception. Not the rule.]

So please do not get discouraged when you have to help the same child to Blend As You Read for the 7th time today.

Or, do not just give away the word when you've feel as if you can't slog through another slow-to-get-through passage.

Rather, think of each minimally invasive type of feedback that you give as a significant deposit in their bank of word attack skill.

Enough deposits and the child will become an independent decoder. And other exciting literacy lessons will await her.

Yes, some students need many fewer deposits, so that may be why we get discouraged or tired of offering feedback to the slower student.

But she'll get there! If you provide her with sufficient sound-based decoding instruction and lots of reading and re-reading practice with specific, targeted feedback, she Will. Become. A. Reader.

Great support for reading teachers Marni! Thanks for your continuing efforts to develop teachers’ skills as they support readers!

Terri, thank YOU! You made my day! Thanks for using and sharing the ideas.

These are so helpful. I wish i learned these long ago .

My son is so stubborn and gets so mad when i correct him. I will. Absolutely use these methods starting tomorrow.

May it serve you both well! 🙂

Thank you, this video is great. It really helped to watch the pupil read and try to work out the type of problem.

That focused my brain.

I will definitely try this.

Glad to hear Blanche! 🙂

Thanks for the article. This is how I intuitively helped my own children learn to read. I was taken aback when I was taught by teachers in my school how to teach children to read as it just didn’t feel right. That is, using pictures to guess the words and taking out the ‘big’ words by reading these words for them.

Yes, it was a belief that goes against common sense. But it gained traction for decades…

These are great tips. I’ve been following Reading Simplified for a while now and it has changed my practice. Now trying to influence my colleagues who are still asking children to look at the pictures. The Reading Simplified methods have made my understanding of the process of learning to read so much more methodical- thank you for sharing. Ultimately, a lot of beginner readers out there are benefitting!

Thank you for sharing your success and for spreading the word Sheila! 🙂