Research has made a powerful case for the importance of systematic, explicit phonics.

But just how explicit do we need to be? What does research tell us and what are the limits to what we know?

Let's talk about the level of explicit phonics instructional directness that we need to implement as teachers or parents teaching kids how to read.

We might not have to be as exhaustive as some explicit phonics programs would advise us!

Instructional Directness: How explicit do we need to be?

[If you'd rather read the transcript from the above video, here ya go...]

Demystifying the Science of Reading

This question of explicitness plays into the system that we have developed here at Reading Simplified. So, I want to talk about instructional directness. How implicit and how explicit do we need to be?

The first journal from The Reading League just recently came out.

The first article in this journal is from Dr. Mark Seidenberg, (who is well known for writing the book Language at the Speed of Sight) and his colleague, Matt Cooper Borkenhagen. Their article is entitled "Reading Science and Educational Practice: Some Tenets for Teachers."

I think this is a really great article and I encourage you to check this journal out because they're trying to disentangle the differences between what we know from research and what we know from general best practice.

There's an art and a science to teaching reading. However, we don't want to overextend what we know from science by labeling things that aren't quite true.

There was one section that got a little attention and caused some debate. I think it’s worth bringing to your attention as it revolves around this question of explicit or implicit learning. Within the article, they claim…

They are both in agreement that although it’s hard to balance the two (implicit learning and explicit instruction), explicit phonics instruction will serve most students very well.

The brain learns to read by translating the sounds we hear into letter sounds that we build to put into a combination to make words that we recognize by sight.

So, explicitness and phonics and systematic - that's not in question - but then, what is the limit to how much explicitness we need to achieve?

Finding Balance Between Implicit & Explicit Phonics Instruction

Seidenberg and his colleague say there is an overdoing it of certain types of explicitness. For instance, they give this example:

“We are thinking here of phonics curricula that entail instruction on large numbers of rules (starting with all of the potential pronunciations of isolated vowels).

Here is a spelling lesson from a popular instructional program: "listen to this word: BUZZ. You need to double the final letter when you hear the "z" at the end of a one-syllable word right after a short vowel."

Seidenberg and his colleague go on to say…

“That rule is 25 words long and hard to comprehend or remember. Then think of how many such rules are required to spell common words in English.”

They claim that this approach leans way too heavily on the explicit side. So how do we decide what is too much and what is just right? How do we get to that Goldilocks effect?

They continue to explain…

“The optimal balance is somewhere between these extremes. The issue has been studied in the field called "machine learning," which is the study of computer systems that learn. The procedures used in training these systems are closely related to the ways that humans learn. For many types of problems, the most efficient type of learning is what is called "semi-supervised." It is our best account of the balance between explicit and implicit learning. For problems such as learning how to pronounce letter strings (or spell), a large amount of implicit learning combined with a smaller amount of explicit instruction seems to be optimal.”

If you have heard people talk about the science of reading and the importance of systematic explicit phonics, this type of persuasion, (emphasizing the benefits of implicit learning and the fact that this is how we're going to teach our kids to read), may be a little surprising to you.

So, I want to unpack this and give you a vision for how this can be a better way than maybe some of the traditional approaches you’ve been relying on.

A Historical Look At Instructional Directness

Let's think about instructional directness in terms of these categories:

First, we'll go through a little history lesson!

Implicit is when there has not been much teacher oversight. The student needs to deduce how things work in the case of learning how to read words. Students need to deduce the code or how to recognize words, and how to read words.

Explicit is on the other end of the continuum where the teacher guides the student to understand parts of the code.

“This is the letter P sound /p/ and this letter combination SH is the sound /sh/.”

The teacher using explicit phonics instruction will help (in part) to unpack how the students need to break up the words.

This is the typical dichotomy that we've been dealing with for decades. In fact, it goes back to before 1967 when Harvard professor, Jeanne S. Chall, wrote “Learning to Read: The Great Debate.”

In this book, she elucidates how these debates between implicit and explicit phonics instruction and learning have been going on for a long time. But she comes to the conclusion after doing a very rigorous research synthesis. She doesn’t just spout her opinion but analyzes all of the studies and concludes that the implicit methods, where there's an emphasis on meaning and particularly whole word recognition, fares pretty consistently less well compared to the code emphasis.

So, even as early as 1967, we had a research synthesis that code-emphasis explicitly taught was going to give us better outcomes for students of all types, particularly students from lower SES backgrounds or with some challenges in learning.

Although these ideas have been around for a while, we're still debating implicit vs explicit!

The amount of research has continued to grow, but whole language got a footing firmly in the implicit camp - that if we surrounded our students with great literature, they would derive how to recognize words. They would deduce the code and they wouldn't need all of that "low level" explicit phonics instruction.

Balanced Literacy & Implicit/Explicit Phonics Instruction

Fast forward a few decades to the National Reading Panel’s report in 2000 that gave a pretty overwhelming case that we really need to have explicit phonics. The whole language movement took a bit of a beating, but then there was a modification.

Instead of swinging entirely over to explicit phonics instruction, there was a movement towards explicit without abandoning some roots of implicitness. We came up with "balanced literacy" where meaning is still taking a really big front stage, so to speak, for the beginning reader in early instruction. This occurred despite the fact that we have had a lot of research that indicates that explicitly showing kids how the code works is the better way.

Explicit phonics is documented to be clearer and draws out both beginning and struggling readers’ achievement more easily.

So, that's one of the ways to think about some of these terms. Implicit on one end of the continuum, where it's whole language and maybe they don't teach any phonics at all. Then we have balanced literacy, where we're seeing the phonics get embedded there mostly because of the impact of the National Reading Panel and other scientific advances and dissemination of these ideas.

Still, the emphasis on phonics and teaching decoding initially--and being very explicit with it--continues to take a back seat in many balanced literacy programs. It’s been labeled as "putting the phonics patch on whole language"– as in, sprinkling in a little bit of phonics, but still leading with,

"let's make a guess,"

"let's look at the pictures,"

"let's focus on meaning," and

"let's look at the whole word while these other things are more on the implicit end."

Finding the Sweet Spot of Explicit Phonics Instruction

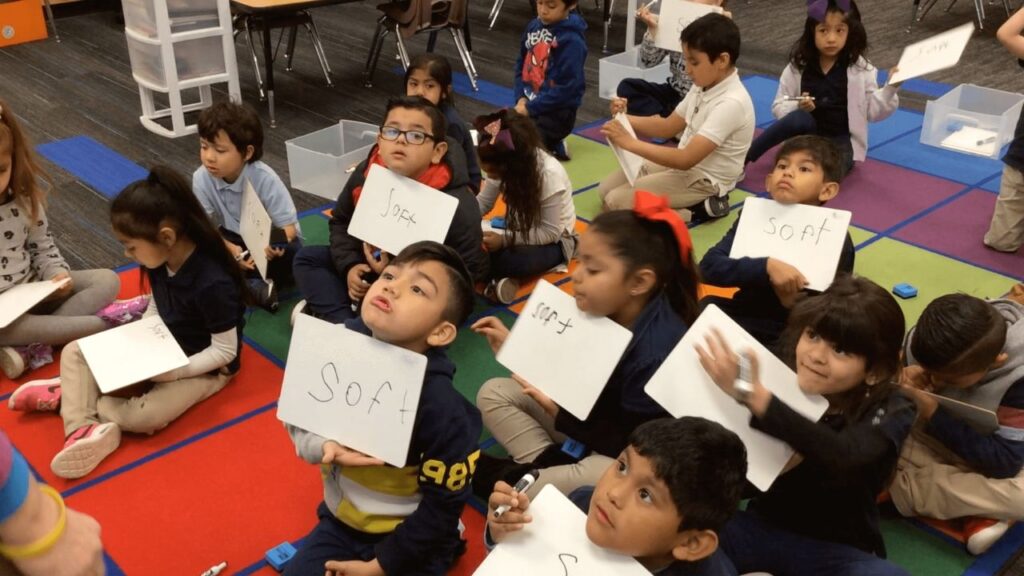

Kids benefit when we show them how the code works rather than asking them to figure it out on their own. We can help them by providing them with the tools for how it works, which mainly means learning the letter sounds and learning how to perceive the sounds in words, (which is phonemic awareness). And learning it to a sophisticated level, which would be advanced phonemic awareness, and learning how to put these skills together in the context of print and reading a lot.

Those things are very important. But, when we get worked up about being explicit with this instruction, we need to make sure that we don't tip over into being exhaustive.

We don't need to teach everything explicitly. How can that be? Well, let's talk about how to tease apart what is explicit and what are the limits of it. We can avoid the exhaustive end of the continuum where every single thing that possibly could be covered in the written language is taught and we can move towards a balance.

I call this balance the ‘sweet spot’ between what's needed in terms of explicit phonics instruction and to facilitate the child's growth.

We have figured out a system for doing this here at Reading Simplified where we're explicitly teaching the code and giving students the tools for how to attack unknown words, but we're also developing their own skill of deducing more and more of the code.

If you look at theory and research about how we learn to read, you'll see that we can't expect the teacher to explicitly teach every single iota about the written language and every little letter-sound combination.

This is the sweet spot that we have reached with the Reading Simplified system...

We are being explicit, teaching sufficient phonics knowledge, phonemic awareness skills, blending skills, and reading practice for the student to be able to deduce more about the code and be successful on their own.

Again, this is what we're seeing from Dr. Mark Seidenberg and Matt Cooper Borkenhagen’s article inside The Reading League Journal:

“For problems such as learning how to pronounce letter strings (or spell), a large amount of implicit learning combined with a smaller amount of explicit instruction seems to be optimal.”

It’s important to realize that explicit phonics instruction that's taught systematically to students will get the best outcomes for most readers. But the little nuances of every single instructional turn that we need to make as teachers has not been proven yet.

There are many things left for us to discover and we shouldn’t argue about one phonics type of program versus another type of program based on whether it’s explicit enough. We have defined that we need explicitness, but we don't have proof about the degree of explicitness.

The Self-Teaching Theory

The self-teaching theory suggests that most of the learning is implicit. David Share’s research on the self-teaching theory in his paper, Phonological Recoding and Self-Teaching: Sine Qua Non of Reading Acquisition (1995) questions how we can get kids to learn independently when there’s such a great volume of words.

“Neither contextual guessing nor direct instruction, in and of themselves, are likely to contribute substantially to printed word learning, the ability to translate printed words independently into their spoken equivalents assumes a central role in reading acquisition.”

According to his self-teaching hypothesis, each successful decoding encounter with an unfamiliar word provides an opportunity to acquire the word specific orthographic or spelling information. That is the foundation of word recognition. That's what the self-teaching mechanism is--the student has a sufficient amount of information to get close to decoding the word and then he/she deduces some of the things that they didn't know before to successfully read that word. Once he/she has decoded it, it may become orthographically mapped. It may become cemented as a unit, so to speak, and become a sight word.

David Share goes on to say….

“A relatively small number of (successful) exposures appear to be sufficient for acquiring orthographic representations both for adult skilled readers and young children. In this way, phonological recoding (decoding) acts as a self-teaching mechanism or built in teacher enabling a child to independently develop both word specific and general orthographic knowledge."

"Although it may not be crucial and skilled word recognition, phonological recoding or decoding may be the principle means by which the reader attains word reading proficiency.”

In other words, it’s the reader’s practice of reading that helps him/her learn more words. The teacher does not need to teach the student every word and every letter-sound combination.

So, that's where this implicit and explicit dance has to be acknowledged and we as teachers need to be sensitive to it and not expect that all of the rules must be learned explicitly before we give kids the opportunity to try something new or something hard.

A Self-Teaching Case Study

In Share’s paper, he makes a logical case based on the effectiveness of the self-teaching theory as it relates to learning and recognizing words.

Here is an example of how the number of words a high achieving reader knows increases as they progress through different grade levels:

Do you think a teacher taught this reader every single word and every single letter sound combination? Did a teacher teach this student that the ‘ci’ at the end of the word is the /sh/ sound? Maybe that was explicitly taught, but maybe it wasn't explicitly taught because the student may have deduced it based on other opportunities that he had that were explicitly taught to him.

That's the basis of Share's self-teaching hypothesis which is very strongly documented and proves that we need sufficient phonics knowledge, sufficient phonemic awareness and practice decoding. Those things wrapped together allow the student to generatively learn more and more about words through, what Share refers to as, ‘word learning trials.’

Word learning trials are implicit.

Many kids, particularly those with poor phonemic awareness, have to be explicitly taught how to perceive the sounds and words and learn how the code is presented. They have to be given the concept of the alphabetic principle and they have to be taught a sufficient amount of phonics information (such as the consonants, constant diagraphs, short vowels and many advanced phonics like the OA in boat and the OW in show and the OE in toe).

Maybe they have to explicitly be taught that, but do they have to be explicitly taught that the PT in pterodactyl is /t/? Maybe they figure it out based on all the other information they're bringing to the task at hand.

So, that's why I want you to grapple maybe a little more than you have before with this notion of explicit.

Don’t Teach Exhaustive Explicit Phonics Instruction!

There's a sweet spot that's not all the way implicit because that’s not going to work for a lot of our students, particularly our students from low SES backgrounds, those who are English language learners or those who may have difficulty learning to read.

So, yes, we do need to be explicit, but there is a sweet spot of explicitness that we need to balance. Finding that sweet spot can be an art form and we need to be careful that we don’t tip over into being exhaustive in covering every single thing.

Balancing implicit learning and explicit instruction is hard and it is probably something that we need to study more now in this new decade.

At Reading Simplified, we have found a sweet spot and we know how to balance implicit and explicit phonics instruction.

We find that kids don’t need to know all of the rules and that they don't need to be taught every single letter-sound combination. We give them a sufficient amount of information and we develop strong phonemic processing skills and advanced phonemic awareness. We do this with activities that are always tied to words, print and meaning.

We are really pleased with the balance that we have found here with the Reading Simplified system, and I encourage you to give it a try.

We figured out a balance between the extremes of completely implicit and the other extreme of exhaustive explicitness that helps the teacher from being overwhelmed because there's clarity in what specifically needs to be taught and it also accelerates students' reading achievement more rapidly.

The activities that we use in the Reading Simplified system are very similar to the activities that are taught in the interventions that David Kilpatrick talks about in his book, Essentials of Assessing, Preventing, and Overcoming Reading Difficulties.

Towards the end of his book, he talks about the interventions that get pretty dramatic results -standard score points of 14 to 25. Those are an anomaly. They are way more powerful in outcomes and efficacy and efficiency than the other programs that are mostly available to the public.

If you want to find out more, head over to readingsimplified.com/Academy to explore the training we offer to help you learn the system, so you can reduce the exhaustion of explicit phonics instruction and streamline reader’s achievement.

What are your thoughts on all of this? Do you lean more towards implicit or explicit phonics instruction?

Or, have you found a balance between the two? Let me know in the comments below!

I find the discussion about implicit/explicit interesting, and it has come up in various discussion groups. Implicit doesn’t have to be completely “go let the kids figure it out on their own.” I’ve seen programs that have students successfully learn e.g. spelling patterns and deduce common spelling/pronunciation rules through the use of word sorts rather than just teaching the kids “the rule for using a CK is …..”. I’ve used this method and have found it to be effective with students who struggle to read and especially spell. Perhaps part of the success lies in the fact that the students have to pay close attention to the differences in the sets of words (I’m guessing here). Another example of guided implicit teaching is the “Reading Simplified” method of teaching sound/letter correspondences where students basically figure out which letter matches up to the spoken sound. On a broader scale, depending on the amount of exposure to print and the abilities of the child –even before they actually learn to read, children display knowledge of some of the “orthographic rules”- e.g words don’t begin with the letters “ck”, some letters double but usually not at the beginning of a words, etc.Maybe that’s a good argument for using decodables texts and ones that have high frequency words in the them and also exposing kid to (not necessarily having kid memorize) multiple spellings of a “sound”.

I love this point Sarah! It’s about the presentation of materials that our students are given the opportunity to notice patterns. So we can do a sorting activity or a searching activity or use a strategic decodable reader, and kids are more likely to absorb our language’s patterns.

Thanks for sharing your reflections.

Thank you for introducing this debatable issue of implicit and explicit phonic instructions.

What I may add to this dichotomy is that the sweet spot varies from one child to the other.

Here comes the role of both the teacher and the parents to help the children who struggle with reading to be exposed to many but short periods of relaxed reading time, where they get to self -teach more.

100% Great point Dalia! Yes, child motivation and ability factors are huge variables in our instruction.

Is the essential phonics for reading the same as the essential phonics for good spelling? I’m all for leaving out instruction that isn’t essential, especially for kids who are struggling with learning to read, but they need to be able to spell too!

needs, but they need to be able to spell too!

Agreed. The self-teaching theory (e.g., Share, 1995) suggests that most knowledge about the code comes through self-teaching while reading. SO, if we can get kids reading a lot and early, then they are best equipped to pick up spelling insights. Many of these insights come from writing practice and again, good readers, have a leg up there and will get in more writing practice. It’s not a either/or but a both/and situation.