You're eager to learn more about the Science of Reading. You're frustrated that you didn't learn some core concepts about how the brain learns to read in undergrad… or from the curricula at your school. You're also too busy to tack on an entire master's in linguistics or reading.

This series of Summer Science Shorts for Streamlined Success may be just what you're looking for!

Watch the video below (or read for more depth below) for our kick-off:

AND, snag a hyperlinked PDF timeline of the heavy hitters of the research world in the teaching of reading words as well!

Science Shorts #1–Do You Believe?

Expanding the Above Science Short #1

The Reading Wars Despite the March of Science

Most people think the biggest fallout of the Reading Wars (i.e. ….

…) is the millions of kids haven't learned to read well, or all the teachers who have been misled. These are indeed tragic consequences. Another rarely acknowledged side effect of the wars is that phonics programs mostly stagnated and their struggle against whole language, and later balanced literacy, phonics was clearly always in the right, right?

The Research and Communication of How the Brain Learns to Read Words

But over 50 years, the science of how the brain learns to read has marched steadily forward discovery after discovery.

For instance, see these significant reviews that included or focused on word learning instruction:

- The 1967 national study by Harvard's Jeanne Chall, Learning to Read: The Great Debate, in which she concluded, “A code emphasis tends to produce better overall reading achievement by the beginning of fourth grade than a meaning emphasis” (p. 137);

- The classic 1975 textbook, The Psychology of Reading, by Eleanor Gibson and Harry Levin states, “[T]he beginners must learn to use spelling-to-sound correspondences; there is nothing in language behavior or other content previously acquired by the child that will transfer to this aspect of the reading task” (p. 323-4);

- The U.S. federally sponsored report from 1985, Becoming a Nation of Readers, by Anderson, Hiebert, Scott, and Wilkinson concludes, “The foundation of fluency is the ability to identify individual words. Since English is an alphabetic language, there is a fairly regular connection between the spelling of a word and its pronunciation. Every would-be reader must ‘break the code' that relates spelling to sound and meaning. Research suggests that, no matter which strategies are used to introduce them to reading, the children who earn the best scores on reading comprehension tests in the second grade are the ones who made the most progress in fast and accurate word identification in the first grade” (p. 10-11);

- Marilyn Adams' 1990 literature review, Beginning to Read: Thinking and Learning about Print, in which she concludes, “[R]eading depends on connections between spellings, speech sounds, and meanings” (italics in original; p. 234);

- A popular press book in 1997 by psychologist Dianne McGuinness, Why Our Children Can't Read: And What We Can Do About It;

- The 1998 literature review hosted by the U.S. National Research Council and written by Snow, Burns, Griffin, Preventing Reading Difficulties in Young Children, that notes, “Truly productive reading, the ability to read novel words, comes only from an increase in orthographic representations that include phonology. This requires attention to letter stings and the context-sensitive association of phoneme sequences to these letter strings…Children who have attained this level of reading can read pronounceable nonwords, and their errors in word reading show a high degree of phonological plausibility” (p. 73).

- The meta-analytic report from the U.S. federally funded National Reading Panel from 2000 that states, “Findings provided solid support for the conclusion that systematic phonics instruction makes a bigger contribution to children's growth in reading than alternative programs providing unsystematic or no phonics instruction” (p. 2-92);

- Other national reports, such as the U.S. federally funded report of the Early Literacy Panel in 2008, the so-called Rose Report from the UK in 2005/6, and the 2005 Rowe Report from Australia, similarly conclude that guiding students to learn how to decode with phonics and phonemic awareness is superior to whole word or unsystematic approaches;

- A literature review by eminent researchers in 2001 Rayner, Foorman, Perfetti, Pesetsky, and Seidenberg, “How Psychological Science Informs the Teaching of Reading,” that says, “The instructional goals for alphabetic systems seem clear: Children need to learn that the letters of their alphabet map onto speech segments of their language…[F]or more than 30 years, research has supported the effectiveness of methods that are based on direct instruction in phonics or decoding” (p. 43);

- A popular press 2007 book by neuropsychologist Maryanne Wolf called, Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain;

- Neuroscientist Stanislas Dehaene's 2009 popular press book, Reading in the Brain: The New Science of How We Read;

- A 2015 by school psychologist David A. Kilpatrick, Essentials of Assessing, Preventing, and Overcoming Reading Difficulties;

- A 2017 book for the general public by cognitive scientist by Daniel Willingham, The Reading Mind: A Cognitive Approach to Understanding How the Mind Reads;

- Cognitive scientist Mark Seidenberg's 2018 book for the general public Language at the Speed of Sight;

- A more recent 2018 literature review by eminent researchers Castles, Rastle, and Nation, “Ending the Reading Wars: Reading Acquisition from Novice to Expert,” states “We have established that learning to read in an alphabetic writing system such as English requires the acquisition of the alphabetic principle—the insight that the visual symbols of the writing system (graphemes) represent the sounds of the language (phonemes). We have also established that virtually all children require at least some assistance in learning this principle. Foundational skills such as phonemic awareness and letter knowledge are key precursors to this alphabetic insight, and these skills and bodies of knowledge interact reciprocally in complex ways….” (p. 11-12); and

- The unique and widely cited audio documentaries by Emily Hanford of APM that catalyzed the recent “Science of Reading” movement–summarizing the failure to acknowledge reading science.

Change in Phonics Methods Have Been Minimal

And at the same time, most phonics approach approaches have stayed locked in their original paradigm from the 1930s or fifties. Some have tacked on a little more phonological awareness or phonemic awareness, but they have not revolutionized their system in light of the contemporary research. (McGuinness' Why Our Children Can't Read offers a critique of the phonics and whole word status quo.)

This series will attempt to help set this right. 😉

Join us for Summer Science Shorts for Streamlined Success.

Do You Believe?

For our first Summer Science Short, we'll discuss both the science we need to know and belief we need to have. If you're a teacher, a parent, if you're a member of the community–all of us–need to know that reading researchers have demonstrated several times over that with evidence-based instruction the “failure” rate of should be as low as 2 to 5%.

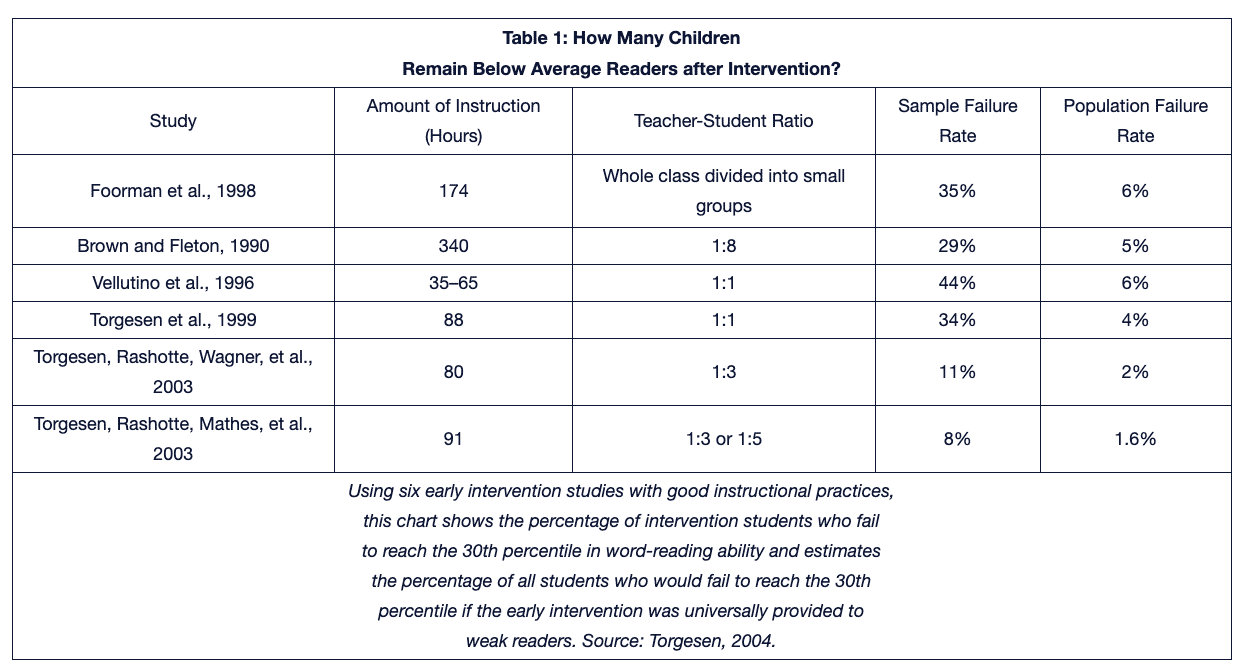

Esteemed reading researcher Joe Torgesen has summed up the power of evidence-based instruction–especially for those who might be expected to struggle. For instance, see this chart below from the American Federation of Teachers' journal American Educator in an article, “Avoiding the Devastating Downward Spiral.”

As Torgesen points out, when one extrapolates from a cohort of identified struggling readers who received intensive evidence-based instruction in either K, 1st, or 2nd grade, one can expect that as few as 1.6 to 6% of the general population should expect to still struggle.

This stat is at great odds with the U.S. rate of nearly 65% of 4th graders not proficient and over 30% below basic!

In other words, about 95% of kids should do fine in reading if they are given evidence-based practice and instruction with sufficient intensity in the early grades. Yet this is far off our current mark with over a third of our students below basic levels.

We clearly have a disconnect between research and practice. That is why Reading Simplified exists–to synthesize the powerful findings of decades of research with the art of teaching and present a practical, streamlined approach for teachers that will accelerate all students' reading.

So my question for you today in light of the research that demonstrates the potential of almost every child to become a good reader…

Do you believe?

Do you believe that we need to change?

Do you believe that almost every child in your care should be able to learn to read?

Good Morning Dr. Ginsberg, Our Maine RSU 71 school district is balanced literacy with a heavy emphasis on 3 cueing with no phonics. It was announced at the last board meeting that 1:4 primary students are being referred to Special Ed. The schools answer to this is EL Education, implementing a soft start in the spring and full curriculum next year and superintendent says it will take 3 years to know how successful the program works. This brian science and empirical evidence of how students best learn to read is just what is needed to convince the board and administration that students need evidenced based reading methods in our school. That is if high literacy achievement is our goal. Thank you Marnie for being such a guide to so many. I’ll do my best in sharing the science with them.

Adam, I’m sorry we missed your comment earlier. But it’s great to hear that your district is making changes and you’re dedicated to ongoing learning and leadership. Personally, I’d expect results in Year 1.

I really got an incredible benefit , as an English teacher with experience of seven yeas. and we can say this is a vivid example of modern teaching methodology.

Super! Thanks for sharing Jacob.