Several months ago I was visiting a preschool classroom and the teacher asked me a question based on her bi-annual PALS assessment. The assessment includes phonological (sound-based language) awareness, letter name, and letter sound knowledge.

She and her co-teacher both observed some quirky responses but didn’t understand the root. She wondered:

“Why do several children say, /w/ for the letter ‘y’?”

Think about the sounds we say when we say the letter name for “y” = /why/. How would you have responded to this teacher? Here’s the route I took:

“Those children have first learned the letter name of ‘y’ and they hear the first sound in the letter name ‘y’= /w/. They know sounds are important but they do not know that sometimes the letter name has nothing to do with the sound the letter usually makes.”

The Two Worldviews Dilemma: Letter Names vs. Letter Sounds

This scenario reveals a critical problem in the teaching of young children that can be drastically improved if we guide pre-K and early elementary teachers to enter into the child’s worldview.

Pause for a moment and consider what it means that

Several of the children said /w/ for “y”

AND

Both preschool teachers could not reason why they produced this error.

The children, as novice readers, had a worldview centered around sounds. They expected that that letters related to the sounds they heard in words, so they thought about the sounds they heard in the word, “y” (/why/) and responded with the first sound in the word /why/.

On the other hand, the teachers, as adult readers, had a worldview so centered around letters and letter names that both could not even perceive that the first sound in the name of the letter was what triggered the students’ responses.

Both worldviews are appropriate for their respective stages as readers.

Beginning readers need to especially attend to sounds in words and learn how sounds map onto symbols. This is how our written code works—letters and letter combinations represent sounds in words.

Similarly, mature, adult readers have advanced well beyond this close attention to the sounds in words. They still rely on sound-based decoding to read unusual words, but most of the time they recognize words on sight and when they spell, they often think in letter names.

Nonetheless, this gap in worldviews is a major problem for contemporary beginning reading instruction.

We can begin to resolve the gap between the child and the teacher’s worldviews by moving, as teachers, towards the worldview of the child:

Think about the sounds in words.

Throw out your thinking of letter names and perceive, again, the sounds that you hear in words. Read a sentence in a children's book and think about the sounds in each word:

“‘I'm going to like working here,'” said Amelia Bedelia.”

What sounds make up the words “I'm” and “going?”

/i/ /m/ and /g//oa/ /i/ /ng/

Ever stopped to think about the /ng/ sound? Try saying it aloud. It kinda comes through your nose. !!

If hearing the individual sounds in each word like this doesn't come naturally to you, challenge yourself to think more about it in the next few days. Hear a word and ponder its individual sounds. For example, what are the sounds in the word, “though”?

Hint: there's only 2.

A Quick Solution: Manipulatives by Letter-Sound

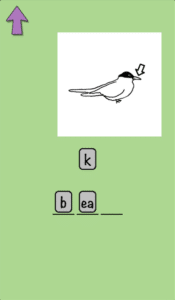

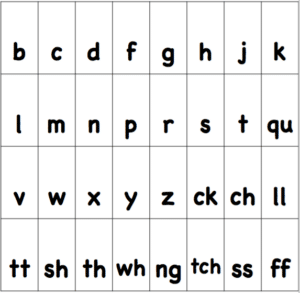

One of the best ways in our classrooms to enter into the child’s worldview and attend better to the sounds in words is to use manipulatives that stress the sound and not the letter name. Thus, use tiles, card squares, or special color to show that each sound is a separate entity.

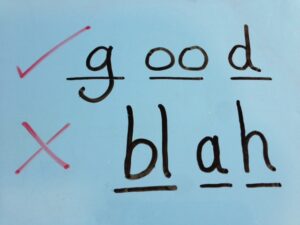

Try: th i s instead of t h a t

We have scoured the world of reading programs and manipulatives and the vast majority treat sounds and letters erratically.

Some sounds are accurately perceived as one unit as in “sh” on one tile. But then the same company will put “bl” on one tile as well, even though it is two sounds. This type of company is living in the adult, letter-name focused world and that shows up in their lack of consistency.

Enter into the child’s world of sound, instead.

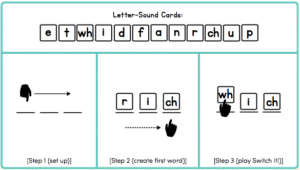

Here are some visuals to show a variety ways of representing sounds rather than letters (including the non-example of “blah”):

We use these letter-sounds cards to teach beginning letter-sound knowledge with an activity called Build It, which I wrote about here. That's a great beginning activity for pre-K and beginning K readers. For everyone, however, we always use these letter-sound cards for Switch It, which is described with a video example here.

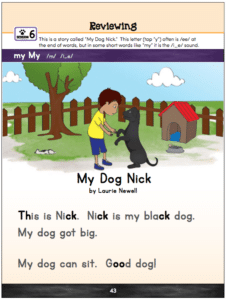

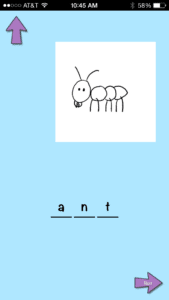

Also, especially for children first learning the ins and outs of our code, we often use texts that have been coded, as in the example from our “My Dog Nick” passage below. The “th” in “this, “the “ck” in “black” and “Nick” and the “oo” in “good” are bolded to show the young reader that those letter-sounds combinations represent one sound. Children don't need this scaffold for long; however, it is helpful for the first few weeks (sometimes months) to help them recognize more of the 250 letter-sound combinations 😮 our English code has. Finally, besides the 3-D manipulatives you use, also be wary of the digital reading tools your students use for learning how to decode. So many of them ignore or misunderstand the sound-driven logic of English.

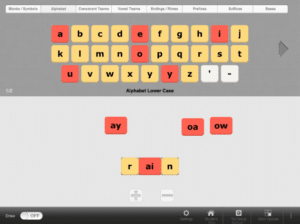

Finally, besides the 3-D manipulatives you use, also be wary of the digital reading tools your students use for learning how to decode. So many of them ignore or misunderstand the sound-driven logic of English.

And please let us know:

What trips you up when you move from the adult letter-bound world to the child’s sound-driven world?

Thanks for joining in the conversation in the comments below!

We tried very hard to orient things to sounds rather than letter names from an early age. I think the hard part is the children’s desire to know the NAME of everything as toddlers. It’s so easy to slip and give the letter name instead of the sound. Also, as the children enter preschool/kindergarten age, they are always asking, “Mommy, how do you spell…?” In retrospect, perhaps when I “spelled” words for them I should have enunciated each sound, rather than giving letter names. Wow! Hindsight.

Ha! Yes, hindsight is bittersweet.

I agree: beginning with letter-sounds is strangely revolutionary in America especially. Letter names are more ubiquitous in pre-K / toddler land than Disney ads. 😉

I believe England is now more letter-sound focused.

My friend grew up in Canada. She wasn’t taught the name of the letter, but was taught the sound. While we recite the alphabet, she would recite the sounds.

Bonnye, thanks for sharing that! Good to know more about the diversity.

Cool memory, too.

Where is the “My Dog Nick” story?

Members of the Reading Simplified Academy can find “My Dog Nick” in the Guided Reading unit under Book Lists and Materials. It the file labeled “1st Grade Guided Reading Short Vowel Review 1” 🙂

We transitioned into a more structured approach to phonological awareness with all our K-2 teachers this year. While we all understood the significance of this, our teachers, especially our kindergarten teachers, had a very difficult time not placing focus on the letters and their names. However, after a couple of weeks of instruction which increased along the phonological awareness continuum, we began to notice the great advances among our students.

Bottom line, all teachers, specifically primary/elementary, would benefit from learning how to teach reading the phonological way.

Thanks for sharing your experience, Leo! It’s great to acknowledge the difficulties AND to be on the other side now.

I agree with your last statement 100%!

As you may know, since 2007 England has gradually transitioned all pre-K, K and 1st Grade from balanced reading to a structured synthetic ( ‘synthesis’ – as in the blending of sounds to make words) phonics approach.

Children begin school a year earlier in England than the US, with the 4-5 year olds learning the basic 42-44 sounds of the English language at entry, including consonant and vowel digraphs/dipthongs . No letter names are used at all initially, only sounds, and they rapidly learn 3 -5 a week – how to write each letter sound, blend them to read words, and how to segment words to spell/write them.

I love the Build-It/Switch It integration of skills, with the window it provides into the child’s thinking, revealing his/her competencies and/or challenges. The prompts are spot-on supporting the child as ‘switches’ are made.

In England, as in Reading Simplified, this basis is then extended into the progression of alternative spellings etc. Children are not expected to read any words with sounds they have not yet learned, and read only decodable books for about the first two years or so which, with the addition of irregular high frequency words and multi-syllable words, grow in complexity – no guessing needed!

Here in the US, I have a new first grade ‘tutee’, who is receiving services for speech and dyslexia. He had previously learned the first 26 ABC sounds plus sh/ch/th/th, but had trouble blending them to make words. Following our first contact, I encouraged the parents to build his phonemic awareness orally. E.g. “Please can you pass the f/or/k. etc. They had fun with this, and I used it as an intro into Build-It, and morphed into Switch-It in the first lesson. He was able to build, sound and read CVC words and, with care, able to switch consonants and vowels. As you discuss in the video (and not yet having seen your progression where you first add double consonants CVCC at the end) I took him to the next level by asking him to change ‘dip’ to ‘drip’, and that is where he and I found he needed support isolating the /r/.

I look forward to progressing through the rest of your program, and to viewing the abundance of extra discussions and videos I see posted. Thank you!

Beth, thank you so much for sharing your thoughts! It’s great to hear the experiences of another successful practitioner. Thanks for your kind words. I’m eager to hear what else you think as you move around the site! I did not know that English students were getting a beginning curriculum with that pace. That’s exciting to hear!

Hi there. Thanks so much for sharing all this valuable information. I really just have to share my frustration with my children’s confusion with the u sound of “uh” and a. It really doesn’t help that in NZ we say “go for ‘uh’ walk” and the letter name “you” doesn’t help much either!

Our pleasure! Yes, it’s not the easiest language to learn…no matter where one lives on earth!

This really brings my thinking together in a nice neat bundle. For years I have been focusing on letter sound connections. With these activities, it is all put together in a way that will build the confidence in students rather than knocking them down with “No, that is wrong..ect” That I found the much more inexperienced teacher doing.

I taught Year 1 and Year 2 way back in the early seventies in Australia. I would always use letter sounds and only vowel names when teaching digraphs. Intuitively, I used to make charts that we used to blend the CVC etc. words together.

Decades later when teaching children with learning difficulties I did the same thing and we had some excellent practitioners in Perth who designed digital and printed resources for this purpose.

Thanks for sharing this story Mary!!

Dear Marnie,

I also appreciate the focus on letter sounds, and shapes that stand for sounds, rather than always using the letter name. However, I taught in a district that stressed letter names, and I developed several lessons to help children who are confused. I taught one lesson for the letters whose names start with the sound (b,d,j,k,p,t,v,z), a little lesson on c and g, those whose name ends with the sound (f, l,m,n,r,s,x) those whose name doesn’t help much with the sound,(h & q) and then three letters which are out to trick you — u, w, y. I had hand motions to go with each of these three letters. By focusing on the problematic letters, the others were learned quickly and easily.

Clever compromise. Thanks for sharing this idea Margaret!