As teachers, we often find ourselves frustrated and challenged by the limitations of current reading instruction programs.

While some students excel and become confident readers, there are always those who struggle to grasp the complexities of phonics rules, exceptions, and patterns.

But what if there was a more effective approach to teaching reading that could unlock the potential of even our most struggling readers?

…One without all the rules.

Today, we're looking into the mystical world of the FLOSS Spelling Rule…and uncovering some of its secrets!

Do our young readers really need to know the FLOSS spelling rule?

I'm here to debunk the growing belief of the more phonics rules the better!

If you're wondering how to lighten the cognitive load for your students – read on! [Estimated reading time: 5 minutes, 46 seconds.]

Or…press play and witness the magic unfold in this 7-minute video!

The FLOSS Rule and Its Sorcery 😉

First things first, what is this “FLOSS Rule” of which we speak?

The “FLOSS Rule” is the guideline stating that

in one-syllable words, the letters “f,” “l,” “s,” and “z” are usually doubled at the end if they follow a short vowel.

As in these words: will, grass, hill, and buzz.

If you want your students to know how to apply this rule easily, they also need to deeply understand what a

- syllable,

- open syllables,

- closed syllables, and

- short vowels are…

As well as quite frequent exceptions such as:

- us

- is

- this

- has

- if

- of

- was

- his

- as

- yes

- chef

- gas

- clef

- nil

- bus

- pus

- plus and

- dear old Gus.

Got it?

With the Reading Simplified method, we have discovered the value in simplicity over complexity.

So we generally don’t find students need to learn complex phonics terms, rules, or their exceptions like the FLOSS rule in order to become good readers.

It’s true, most students can learn to read words such as these quite easily in the context of Reading Simplified instruction.

Yes, even in Kindergarten.

Notice below how in the top 300 most frequent words (which make up about 65% of written English) the so-called floss “rule,” is by far the exception.

Should we teach a “rule” that is contradicted by these most essential, early words that children need in order to begin successfully reading transitional texts such as Little Bear, Frog and Toad, Messy Bessey, or Henry and Mudge?

Simple, but Disarming

How can this be, you're wondering?

If you’ve been discovering the importance of the Science of Reading lately and you know kids need to be explicitly taught phonics, you’re right.

So you’re probably wondering how can this be that a reading program based on the evidence would tell you to minimize phonics rules?

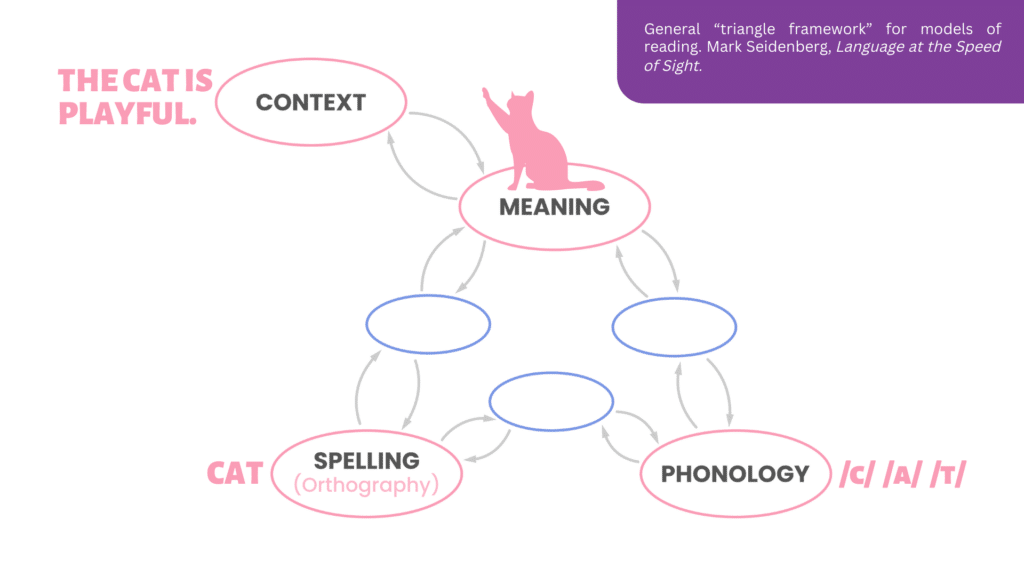

It turns out that in the last 30 years or so, scientists have discovered that we learn to read words less through rule application and more through observation of patterns.

Once we are explicitly taught how the code works and some grapheme-phoneme or letter-sound correspondences, then a lot of our learning of word parts and words is implicitly gathered.

When we read the manual for how to crack the code, so to speak, then our amazing minds statistically computes possible expectations for given spellings in words to help us attack and recognize words with increasing accuracy and speed.

We know this through the research on connectionist models of reading (see image above), the self-teaching theory, and the simple observation that not one accomplished graduating high schooler was explicitly taught all 20,000 to 40,000 words she recognizes in less than a blink of an eye.

See how in the chart below the graduating 12th grader needs WAY more words than they knew in the first few years of elementary (researchers estimate about 20 to 40K!)

Yes, teachers should explicitly help students on their journey towards good decoding, but most of the phonics spellings and words that the student will learn over her lifetime will be implicitly acquired!

The influential cognitive scientist Mark Seidenberg who wrote Language at the Speed of Sight, has been teaching this concept extensively lately.

Recently, he and colleagues wrote, in The Science of Reading: A Handbook:

Traditional instruction is explicit, as in teaching explicit rules for pronouncing or spelling words. Aside from the lack of agreement about the rules, these mappings are far too complex to be wholly taught this way. Although learners benefit from explicit instruction, most of this knowledge is acquired via implicit learning. Excessive emphasis on explicit instruction may make acquiring this material more difficult.

This is good news for us muggles!

Learning oodles of phonics and syllable rules is time consuming and places an undue cognitive load for developing readers.

Not only do we now know that learning to read ignites through explicit instruction, but it mostly runs on implicit learning.

A recent study demonstrated the futility of at least one common phonics rule:

In studying the efficacy of the V|CV pattern as in these words

ze bra

ti ger

bo nus

pa per

"The data suggest that there is really no V|CV division pattern at all."

Dr. Devin Kearns Tweet

Ignite the Enchanted Code

Children need the code, and they need it fast.

Giving students strong sound-based decoding skills and phonics information early on in their development is one way that Reading Simplified teachers build readers rapidly.

Some methods introduce the FLOSS rule in the 1st grade. But why wait?

We believe in empowering our kindergarteners with this knowledge much earlier.

Indeed as early as the first weeks of kindergarten, even absolute beginning readers get exposed to 2 letter graphemes or 2 letter combinations such as /th/, /ss/, and /ll/.

Folding this concept – that 1 sound can be 2 letters – early on is a great way to accelerate student reading.

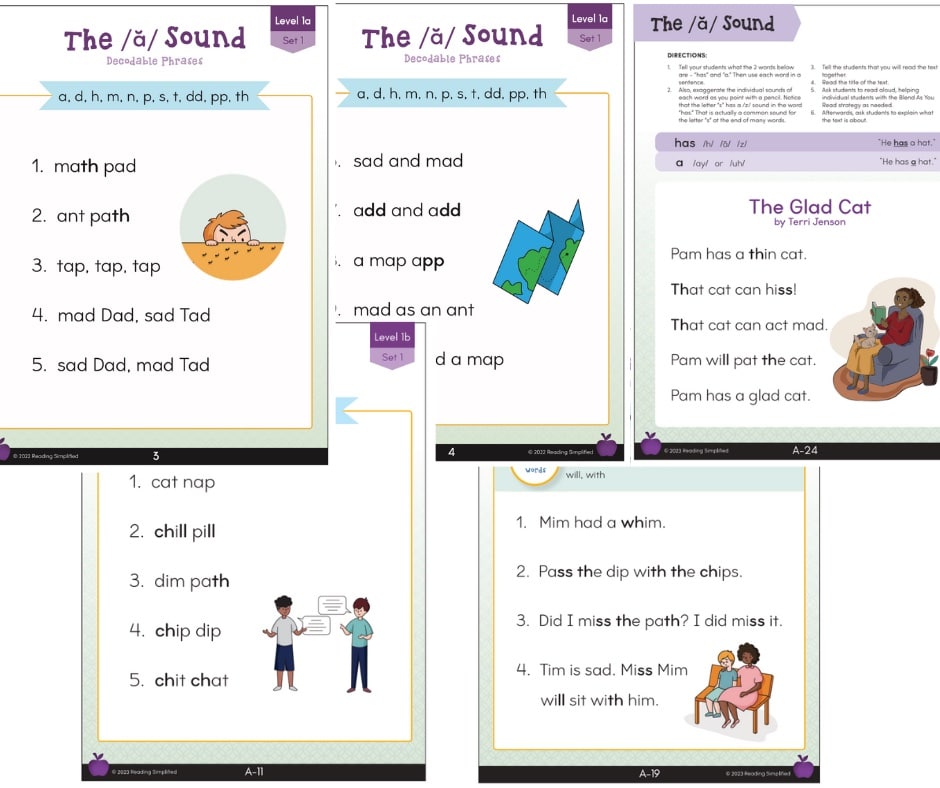

In our earliest reading material inside the Reading Simplified Academy, we still demonstrate this principle of our code. Notice in the image below how the reading texts bold the 2 letter-sound combinations, such as the “th” in “path” or the “ss” in “hiss” or the “ll” in “will.”

When we introduce this principle early on, it's actually quite easy for young students to grasp!

One of our most important activities – Switch It – is a simple way to introduce these easy spelling patterns.

When kids get a jumpstart into real reading like this, and even see the slight complexity of 1 sound = 2 letters early on, then they are on their way to an early introduction to transitional texts.

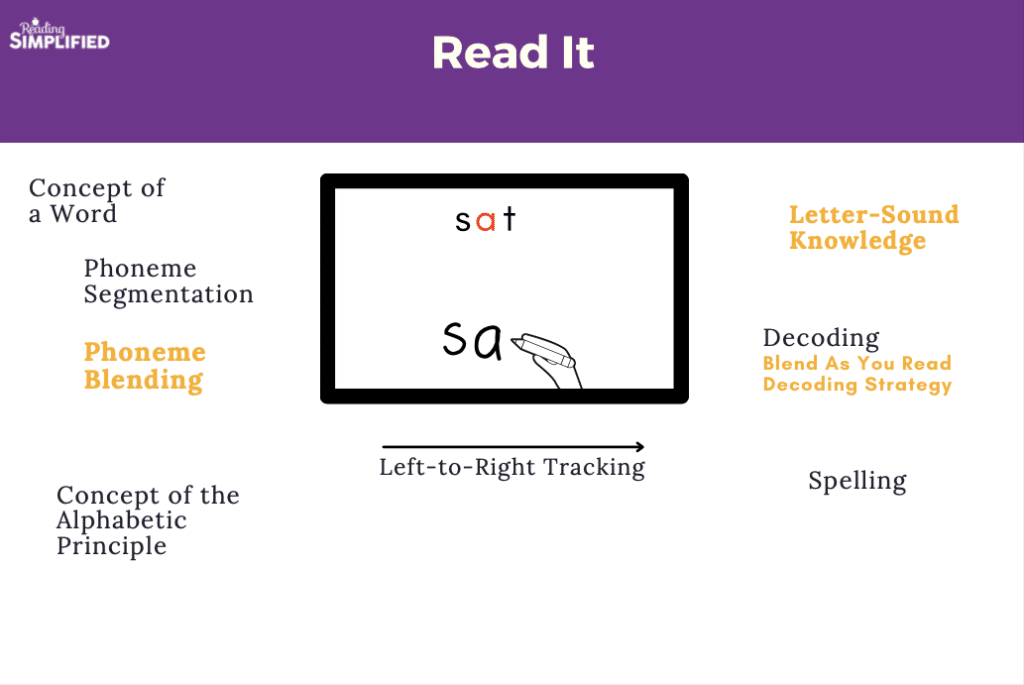

Our next activity Read It and the strategy Blend As You Read is perfect for this next step!

The Magic of Efficient Instruction

Now, the magical finale – let's harness the power of efficiency.

As a result of our more rapid access to phonics knowledge, Reading Simplified students enjoy getting into the enchanting world of books earlier.

They have more time to practice the invaluable skills of integrating all that phonics knowledge with meaning…making real text reading.

Along the way, the Reading Simplified teacher listens along to each student read…giving targeted – but brief feedback.

Our mantra?

Less chit-chat, more magic!

And there you have it, fellow reading enthusiasts! We've successfully debunked the FLOSS spelling rule and its sorcery.

Until next time, keep those books open and those wands ready!

Snap up more info about Blend As You Read with our Read It activity.

Or, if you are ready to immediately be trained in how to optimize Blend As You Read and the other few, vital activities that make up the Reading Simplified system, then please join the Reading Simplified Academy. Learn more about the Reading Simplified Academy.

I totally agree–for reading. spelling though is different for FLOSS. I teach kids to try the rule first, and if it looks wrong, to drop on consonant. They are familiar with the “sight words” and can usually choose correctly.

I can see how spelling instruction may merit a different discussion, Evelyne, like the one with Pam in another comment here. But many reading programs are prioritizing floss and other phonics rules and blocking progress in reading until these spelling rules are mastered. That is my #1 concern as it’s terribly inefficient.

And I completely agree with you about the testing out spelling choices strategy! For those who have been reading for awhile, a visual comparison will help them make the call about which spelling to choose. That might also happen without the rule if we give them the perpetual strategy of “try one spelling, and if it doesn’t look right, try another.”

Totally agree with you Evelyne! I each the FLOSS rulefor spelling purposes, also. I like the “less rules” for reading purposes, but feel kids need some guidelines whenit comes to spelling.

Thanks Laura. I definitely agree that spelling is another kettle of fish than reading.

I’m concerned when I see so many rules being heaped on for reading’s sake when we know that’s not the way in which we learn to read.

For spelling, we still must rely on many implicit skills since there are So. Many. Words. To help draw students’ attention to the patterns they may be overlooking, I find that sorting, underlining parts, reading, and writing words of a particular type is a shortcut to spelling mastery. We always prioritize foundational reading skills first, however, rather that lead with spelling mastery while a child is still developing reading mastery.

Also, a colleague reminded me that we have millions of teachers (and students) who haven’t learned all the ins and outs of sophisticated linguistics rules. If we can get most of them successfully teaching (or reading) in a matter of weeks or months as we can with Reading Simplified, the nuances of complex phonics rules seems less urgent for the masses.

I agree that students can easily learn to read floss words however my concern is learning how to spell them.

This is a fair rebuttal Pam! With the Reading Simplified approach we see children learn to read these types of words so early on that they have had a lot of practice with them. They are easier to spell after one has read them oodles of times.

Another question- is learning a rule the best way to help spelling? What about reading, sorting, and writing words with the target pattern instead during that same amount of time? Might that be a less cognitively demanding task that also goes with the flow of the brain’s statistical learning abilities?

Another great example of simplying things to make more efficient progress. Love the sparkles etc.

May it serve your readers well! Everyone would be a bit happier, don’t you think, if they had more sparkles? 😉

This doesn’t apply to kiddos with dyslexia. Their brains works differently. Reading isn’t something that happens mostly through implicit learning for these kids, it has to be explicit.

I haven’t found that to be the case quite that starkly Jen. I agree that a deep dyslexic will have a harder time with implicit learning and will take longer to learn to read. However, I still get them to learn to read much more quickly than programs that rely on phonics and syllable-type rules in order to succeed. Reading, sorting, and writing words seem more efficient than working on rule mastery.

I imagine that this may just seem preposterous to those who have been teaching students to read via the rules for years. Besides the seeing is believing of working with such quick remediation cases, the more recent research has been very helpful to me in understanding how our amazing brains actually do learn to read.

Two of the articles I link in the post above have been useful for my thinking:

Joanna Arciuli’s article “Reading As Statistical Learning”

Mark Seidenberg and colleagues’ article “Lost in Translation“

I’m in agreement with some other commenters that teaching the floss rule is useful for spelling, and we know that encoding has more impact on decoding than decoding has on encoding – so to me it seems more useful to teach those things at the same time. Plus, I can very quickly identify why many of the exceptions are exceptions, which is a great conversation to have with kids, looking at how the English language works. For instance is, was, as, has, his all end in a /z/ sound, so the s is working differently. Gas and bus are short for longer words. Chef is French is so doesn’t fit the pattern. (Until has been included in the exception list too but this is a two syllable word) I’m also not clear on why students would need to have a deep understanding of open and closed syllables to really get the floss rule?

You state that very early on kids will come across digraphs and double letters so they should be taught how to read them, but in general the good quality decodable readers I’ve used haven’t actually introduced the double final letter early on.

Whilst I think students are quite capable of reading many of these words without being taught the rules explicitly, the rules really support spelling and writing, which is where students at my school fall down – and we haven’t been working with a model of explicitly teaching phonics, spelling rules/generalisations or morphology in a systematic way. I’ve really seen improvements in the spelling of kids who’ve had intervention that incorporates these things for both encoding and decoding in the same lesson.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts Lauren! What we are first and foremost advising is that the research, and our successful and unusually fast gains with students, lead us to push back against the need of for many phonics rules for the teaching of reading.

We also find that encoding practice certainly improves reading and encoding skills – and we also see that in research. However, we don’t see that the encoding practice has to take the time to review rules.

For instance, our activity Write It that one can see in the bottom video on this page:

https://readingsimplified.com/why-phonics-isnt-sticking/

children learn to observe patterns in words if we place common patterns in front of them. For all the time that it might take to teach the exception that I include in the video and the ones that you mention, the child could be sorting, reading, and writing words so that they have more active practice and transfer opportunities.

All told, however, I think the research case against rules for reading is quite robust and less is known about spelling. In my own clinical work, I may enfold a spelling tendency if a child has an important word or spelling pattern that is repeatedly causing her to be stuck. But I am much less likely to find this to be helpful as compared to the challenging Word Work activities and challenging reading and re-reading opportunities.

I guess I’m just trying to say (poorly!) that every instructional minute counts, and I see that the child does best studying and sorting words of a pattern rather than me trying to teach and repeat a rule.

Love this video! So clearly explained! It makes so much sense.

Means a lot from you Tami. Thank you!!

Thanks a bunch really helpful to know this method.

Glad it helps Yamina!

Thank you for sharing this Marnie, I agree with you. I’ve been teaching the OG spelling rules for years and have found some of them to be overly complex, and not hugely effective, especially for children who also have ADHD. (ADHD brains, typically do not like to stop, and analyze before reading or writing a word.)

Also, I find that there are issues with transference from OG to kids’ classroom work. Likely because the cognitive load with some of the rules is quite high and kids simply can’t focus on the spelling at the same time that they are concentrating on what they are going to write.

I think you may get a response from the OG Community for daring to say such shocking things here 😉 …but I’m behind you and I’ll bet there are others! Thanks for sharing this.

Great to hear your experience Nicola. Thank you! Agreed-so many steps makes for harder reading and writing.

Also, yes, many who have been heading upstream against balanced literacy using strong O-G instruction for so long may find the claims in this video/post hard to believe. But the research is moving this way and many of us-Reading Simplified and other speech to print (aka structured linguistic literacy) approaches-see so much faster outcomes without the rules like you.

I have LETRS training, IMSE training, and was a certified Level I Wilson practitioner. So obviously I have extensive knowledge of the OG approach. However, I have often thought that all these rules were overloaded on the brains of students who were already identified as having poor short term memory or poor working memory.I began the Reading Simplified training last year but didn’t complete it. I did the Switch It activity with my lower skill level 3rd graders but I wasn’t seeing how the whole reading simplified fit together. I work with 3rd, 4th, and 5th graders in an intermediate building. The gap is so huge by the time they are in 3rd grade that it seems impossible to close. From the videos I have watched from Reading Simplified, I understand that children are exposed to patterns as early as preschool age or kindergarten. What about students who have not been exposed in their early years? Can I jump into Reading Simplified without teaching some “rules”? Will students just “pick up” on the spelling simply from being exposed to patterns? I am interested in your thoughts.

Thanks for sharing Dianne! We have had many O-G trained teachers express the same concern for their students…how can we ADD more to the task of reading if the child finds memory or sequential processing challenging?

We have heard many O-G teachers sing the praises of Reading Simplified and/or other Structured Linguistic Literacy programs that do not teach the rules. Why? Because they see such rapid growth after months (or more) of minimal growth.

To your question, yes, you can completely expect the older reader to catch up and learn to recognize the phonics patterns. Reading skill comes first and quickly, as you can see with middle school teacher Kathryn whose 30+ intervention students gained nearly 4 years’ growth in just 17 weeks (see post here).

Starting with Switch It is great and the full Reading Simplified requires more than that. You can learn a lot about how we put the pieces together into a 3-part lesson plan here:

https://readingsimplified.com/?s=3-part+lesson

And the easy button is gained by joining our Reading Simplified Academy and learning the full system.

love ya Marnie, but gotta disagree here to an extent. Now, I’ve NEVER taught the ‘floss rule’ in terms of READING. I just tell students that the two consonants work together to make one sound. HOWEVER. If I don’t teach this rule when it comes to spelling, I have kids that spell clif, tos, tal, etc. While I know RS is more reading focused, I have 6th graders that can’t spell the word “they.” (literally today a 6th grade student spelled it THAY). So while I teach reading skills with RS explicitly, I also have to teach spelling rules explicitly. And most of the exceptions to this rule have a reason behind them (ie bus= short for omnibus; was/is/etc are function words, etc). So while in principle I agree that teaching a floss rule for reading is unnecessary, teaching it for spelling is essential. Almost all of my middle school students struggle with spelling. It is a nightmare.

I like how you don’t teach it in terms of Reading. However, new programs are including rules like this as part of their reading instruction….First grade.

I agree that you want to teach a dyslexic reader how to spell the word “they.” Of course! High frequency words are essential for reading and spelling.

But does a reader who is still not fluent need to know how to spell “bliss” or “floss?” You could spend time on that or you could spend time building their reading abilities mostly. I think we’re in agreement…although I do expect that having a struggling speller sort words with 2 types of spellings and asking what they observe would get better results, as compared to teaching rules that are not that reliable or that also require learning several exceptions.