Are there ways to make teaching reading – particularly phonics and word recognition – both easier and more playful? Do I need to know all the rules to teach a child to read? How do read-alouds fit, and is it okay to reread Goodnight Moon to my child over and over again?

These questions niggle at homeschool parents and classroom teachers alike!

I got to spend a fabulous hour talking about these questions and other topics around reading with Julie Bogart and Melissa Wiley of Brave Writer.

These ladies and their work serve the homeschooling community and focus on the writing component of literacy, so it was super fun to change up the conversation with them.

Both contributors make really valuable connections between the principles we use here at Reading Simplified and some of the conclusions they’ve drawn from research and practice around writing!

Please give this a listen, there’s something for everyone and these ladies ask phenomenal questions!

If you're ready to give it a go, get started listening here:

If you’d rather read for a bit, here we go!

The Science of Reading

There is a tremendous body of research and science about how our brain learns to read.

Despite our individual diversity, we almost all need to go through the same pathways to become a good reader.

That’s what science tells us —

Our written language is a code for sounds.

We learn to read by co-opting our language system — connecting spoken and written language is foundational to learning to read.

One of the biggest insights from the science field is that we learn this code by hearing the individual sounds of words (phonemic awareness).

Phonemic awareness is crucial for reading and predicting reading outcomes.

That’s just a little sampling from the science of reading — a vast collection of studies from so many different people all over the world in multiple fields — about how the brain learns to read.

The Art of Teaching Reading

The art of teaching reading is about understanding and adapting.

Whether you're a parent, teacher, or tutor — it's about finding the best path to reach your reading goals in every unique learning situation.

And that's something harder to pin down than some of the findings of science.

Why?

Because those aspects are hard to study with a clinical trial and it involves the observation of human nature — including a great deal of detective work and figuring out what’s working or what’s not for this child in front of me.

Assessment is one way we can take a look at what students are acquiring.

It gives insight first into the two big ideas of reading instruction:

- Word recognition and

- Language comprehension

— And whether one may be more difficult than the other for the particular child in front of us.

We have to marry science and art, or at least try to.

There's a wave sweeping through, spotlighting the science of reading — and it's a game-changer.

Seriously, we're sitting on a goldmine of knowledge here!

And there’s a movement to draw the public's attention to this science.

What we still don’t know, or can’t quite pin down, is whether “activity A” is superior to “activity B.”

We don’t have that level of specificity in science, so we still need to honor the wisdom of parents and teachers who know how to work with the child that’s in front of them and that child’s emotional, motivational, cognitive, behavioral, physical needs and strength.

Debates Around Teaching Reading

Reading difficulty is in fact a crisis in America and most English-speaking countries.

Over 65% of American fourth graders are not proficient in reading.

And the number is even far worse for those in different minority groups or low income communities.

So, when research reveals that a long-standing reading model doesn't sufficiently benefit students — it inevitably leads to heated debates in the education community.

And questions start getting asked:

— Why is my child struggling to read?

— Why is this student falling so far behind?

— Why isn't this curriculum cutting it?

Amidst the COVID-19 virtual learning, a startling number of parents had an eye-opening realization: their kids were struggling with reading

It's a tough realization when we learn that children aren't receiving the most effective reading instruction and as a result — lack strong reading skills.

And even though some students appear to learn reading through such instruction, it's likely quite inefficient.

One first-grade mom spotted a stark contrast between the Science of Reading and how her daughter was being taught in school.

She shares her concerns and observations in a series of videos titled, Is My Kid Learning How to Read?

We actually have known for about 50 years that students learn to read by:

- Picking up on the sounds of the languages,

- Tuning into that information, and then

- Connecting the sounds to the symbols that we blend together to read unfamiliar words.

This process, this hard work of decoding an unfamiliar code, changes our brain.

Then those words become units we recognize in a split second.

It’s rather miraculous how it all happens.

History of the Debates Around Teaching Reading

The debate between the use of a whole word or a whole language approach or the use of a phonics approach goes even as far back as the 19th century.

For about a decade, a whole word approach has been preferred, and it has morphed in the last 20 years to being called balanced literacy.

Some of the time, phonics is actually taught in this worldview, but it’s taught as something that needs to be relegated to last place, not as highly relevant.

The Continuous Unveiling of the Problem with Balanced Literacy

While the pandemic brought its own set of challenges, parents are uncovering deeper underlying issues.

Influential journalist, Emily Hanford of APM reports has done a number of audio documentaries, including a recent six part podcast which I highly recommend checking out.

Her documentary, Sold a Story, sheds light on the events leading up to our current reading instruction predicament.

Julie shares in our conversation a well thought out reflection about and her own research about this debate:

One of the things that stood out to me while I was learning about this was that homeschoolers generally do use phonics to teach reading, right? And that’s obviously the majority of my audience…but there’s a feeling that somehow phonics instruction was tedious and so because it was tedious, they were trying to find a way to circumvent…maybe the hard work of tedium. But ironically, when I taught phonics to my kids, it didn’t have that same level of excruciating pain…So I’m just curious to know, why do you think phonics instruction fell out of favor? And is it this idea that it’s tedious and we’re trying to entertain children?

Julie Bogart of Brave Writer

The balanced literacy community, or previously the whole language community, were very much concerned about bringing the joy of reading to every child, and giving them access to great literature really early.

That is indeed a great goal!

But they were also reacting against a model that may have been highly controlled with lots of rules and a slow start – lots of worksheets, whole class monotony – things that aren’t actually essential for teaching phonics.

At Reading Simplified, we have a much more playful, game-like approach to revealing the code!

Playful and Rapid Access to the Code

It's our experience that we can certainly give access to the code, and the power of how the code works more quickly than some traditional phonics approaches or programs.

We can help students learn the phonics and tune into those sounds, and the words in a playful and rapid way.

We don’t have to drag it out for years.

That’s one of the things I’ve been working on with Reading Simplified and in the reading intervention that I developed before.

One burning motivation for me has been how to really get a nation of kids reading quickly and in a pleasant, easy-going way so that they can quickly get into real books like Henry and Mudge, Frog and Toad, and Messy Bessy.

Reading Simplified is an approach that is streamlined for the teacher or parent and also aimed at accelerating the students reading achievement.

It is certainly in alignment with the Science of Reading.

Some of the things that we’ve discovered is that when you put attention to the sounds of words and connect those sounds with phonics knowledge in the context of real words like,

Let’s build the word “mmmmaaaaap.”

We’d do this using little letter tiles.

When you do that from the beginning, everything connected to the code unlocks really quickly for kids.

That’s only one of the things we do.

Another key understanding rooted in science is that our language system encodes sounds.

By organizing phonics instruction with this in mind, we can achieve faster results.

In contrast a lot of phonics programs teach phonics information organized by print.

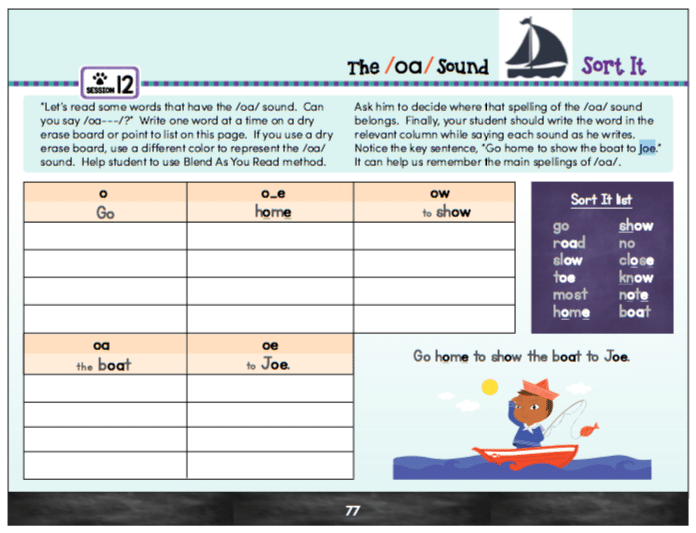

An approach like Reading Simplified, is more of a speech to print approach, where we are more likely to organize the code by sound so when you get to the sound /oa/ we would teach all the common spellings that /oa/ can be, such as the /oa/ in “go” “home” “show” “boat” “Joe.”

We have kids read those words.

The special spellings for the /oa/ is bolded or somehow marked to draw kids’ attention to them.

Then we sort them and they say the sounds as they write the words.

So when they write the word boat, they would say:

/b/ /oa/ /t/

They are making that connection between the sounds they hear and the word “boat” and those squiggles on the page.

This schema, or mental organizational framework, helps kids have a hook for that information, helping this new information to not be so random.

And we can release the code to them really quickly.

In the typical Reading Simplified scenario, a kid would be exposed to the /oa/ sound and spend time on it for just a week, reading old and new texts like Joe and Joan.

Then the next week they would already go to the /ee/ sound like the /ee/ in “he” “meat” “these.”

They would learn all those symbols, connected to the sound, sort more words, and read them in real text.

They would have a chance to gather that phonics information rapidly, and then within a few weeks a lot of kids are able to get into those early transitional texts, which are so rewarding!

Then they really see the snowball of growth in their knowledge of how to read words and recognize word parts which David Share called a self teaching theory.

We know that kids need sufficient phonics information, sufficient decoding strategies, and then they actually teach themselves a lot on the road to reading.

This spurred Julie!

I still remember the joy when I watched my children learn the “ight” without being instructed, right? They learned “light” “night” and there was no teaching it.

Julie Bogart of Brave Writer

The Importance of a System to Reveal the Code When Teaching Reading

If you have a good program for decoding it will move from the simple to more complex.

It’s really important to have a system and that you reveal the code to children systematically, there’s a plan, and you do it gradually.

And then the question is, “How gradual?”

l try to encourage adults to release the code as rapidly as possible so that your child is challenged every time she encounters text and the parent is there to give her support, but we don’t push her to the point of frustration or tears.

If you start with short vowels and consonants, you can clue children into consonant digraphs like “ch” or “ck” – two letters that make one sound – early.

And you want to do this because it reveals the crucial concept that one sound could be more than one letter.

Once the child gets the hang of that world of CVC or consonant-vowel-consonant words where single letter sounds are pretty reliable, she can easily get this concept.

Our experience at Reading Simplified is the more rapidly that we release that code knowledge the more success the child will have, and this comes into the science about how the brain learns to read — its statistical accomplishment.

Our brain observes patterns that appear over and over again and then we subconsciously notice some things about words.

But we can’t pick up patterns if we haven’t seen lots of examples.

We also need lots of examples in real words, and some words are a lot more important than others.

Because only 300 words make up about 65% of written English…those are the words you need to be able to read Little Bear and Frog and Toad.

But we do all of this in really playful ways.

We keep our activities game-like and the “fun of it” front and center.

Switch It is a great example of a playful activity that is also very explicit where the teacher is controlling the phonics knowledge she wants the child to have and the level of phonemic challenge students are getting.

It’s hard to go from “cash” to “clash” because when you add that second adjacent consonant at the beginning of the word it’s just hard for a young child to pick up.

Those consonant clusters are not only hard for speech production for preschool.

They’re also hard for reading absorption or learning.

So in an activity like Switch it that is controlled and yet playful, we have to think a lot about the words we are using and the phonemic challenge they present.

That is kind of the trick of good early decoding instruction for any age.

When you look at the literature of different reading challenges, a common one is that there’s a perception issue with the sounds that make up words.

It’s tricky for certain children to perceive sounds.

So when you’re making slight sound switches in words, they don’t actually get it because they just see squiggle, squiggle, squiggle.

Homeschoolers have generally embraced the teaching of decoding through phonics, so what do they need to know more about?

Phonics Is a Sound-Symbol Code

Phonics has been around forever, and often used in the homeschool community.

It’s never been dropped like it has been in schools.

But a lot of traditional phonics did not have this understanding about phonemic awareness, which is that key that unlocks the ability to crack the code.

It’s not our code alone – it is not just symbols – it is a sound-symbol code.

And so if you don’t quickly process sound distinctions, then it’s hard to make all those connections — those sound-simple correspondences, or phoneme-grapheme relationships — rapidly enough to be able to decode a word.

Many of those kids who were in a phonics curriculum that didn’t help them tune into sound, it may have seemed that phonics alone wasn’t quite working for them.

This blog goes into more detail: How Orthographic Mapping and Phonemic Awareness Research Can Enhance Decoding Instruction.

So it’s really important to discover this from more recent research.

We need to give students information about phonemic awareness and phonics.

But that’s just part of what it takes to become a good decoder — the first step to becoming a good word reader.

There are more steps on the way to fluency and good comprehension.

So more and more modern programs fold phonemic awareness in.

And the ones that do it the best — are the ones that just integrate it from the get-go.

You don’t have to do a separate lesson hearing sounds orally, looking at letter sound cards.

You can just put it all together in the context of words.

Switch It teaches students how sounds and symbols work.

This is one of our most powerful activities for helping kids with phonemic awareness.

Children who struggle often come from a Balanced Literacy environment where the focus isn't primarily on print, or from a strictly phonics program.

Such environments don't explicitly connect the dots for them.

However, some kids manage to grasp this information regardless of the approach.

Phonemic awareness is just like any skill:

There’s people with a natural talent for it — a natural aptitude to perceive individual sounds in language — and be good at language in general, so cracking the code comes easy for them.

It may not be that their instruction was all that spot on, it was just that they had the necessary cognitive equipment to take off rapidly.

Do We Really Need To Teach All the Rules?

There’s another debate in reading —

One that has to do with teaching (or not teaching) lots of rules and syllable types.

Rules and syllable types aren’t essential for learning how to crack the code and learning to read.

They may be helpful for spelling.

I don’t need to write the word “piece” like a “piece of pie” until I’m pretty far along in my journey as a reader.

It actually doesn’t go along with what we know from the science about how the brain learns to read.

We think we’re learning rules.

We think we’re applying a rule if we’ve learned them.

These are things that people talk about, but actually our brain is much more likely to be applying a tendency, it’s based on a pattern of statistical observation, or statistical learning.

Take the word “hat.”

It’s easy to decode.

But what about “have?”

It’s less common for sure, but is it really that irregular?

It’s still a pattern that does occur often in the English language, though a little less common than “hat.”

A word like “eye” will be further down the continuum.

We learn through the statistical observations of patterns and if we can do it in the context of reading with ideally corrective feedback, that’s what we believe is so powerful at Reading Simplified.

So for example when a child reads the word “boat” as /boot/ —

We’re going to point with our pencil at the “oa” and say this is /oa/.

And that little bit of feedback is what helps her to not only attack that word and get a little bit stronger with her sub skills that are going to help her read many more words with the /oa/ sound in it, it’s generative.

It’s going to enable her to read “boat” the next time she encounters that word but it will also help her with any word that has “oa” in it.

So if you try to give kids access quickly, and a playful attitude,

We’re gonna try this sound, and if it doesn’t work we’ll try another,

Then that frees us from a lot of rules.

How Spelling Fits Into the Picture

At the same time there is spelling.

To use rules or not isn’t an easy answer because spelling is actually a very prime tool to help you learn to read.

At Reading Simplified, we start with basically a spelling activity:

“I want you to help me build the word map.”

They’re not writing it necessarily if they are a beginner.

The child may start with pulling down letter tiles for /m/ /a/ /p/.

That’s a spelling activity. We lead with sounds.

Montessori did that over 100 years ago as a way of starting to give kids access to the code through spelling.

So it’s an access to figuring out how the code works but it’s still important to remember your first most important goal is to teach a kid to read.

Spelling can be used to support the activity of reading, the goal, but don’t put the cart before the horse.

Reading outpaces spelling.

Some tips to keep in mind for reading with your child:

- Keep reading aloud – Read aloud to children until you’re hoarse! No matter how old they are, it’s always beneficial. We can make it even more powerful when we read aloud a text two years above their age/grade level. Don’t be afraid of reading harder texts aloud! And focusing on one topic for a time is really good too! Also picture books provide more rare words than even exchanged in a conversation between college educated adults, so keep reading those, too. And if your child has a favorite and wants to read it over and over, that’s good, too!

- Grant quick access – When you are successful at something, you like it, and tend to be more motivated to repeat it. One way we do this, in addition to revealing the code through our scope and sequence is by giving children the opportunity to re-read with new passages. When children re-read, they gain automaticity of words they didn’t immediately know earlier. And as Julie pointed out in the podcast, it’s a fantastic way to support writing as well!

- Move quickly between activities in a lesson – most activities at the word level should take a short amount of time! We can keep children engaged and activities feeling more game-like.

What I Want Parents to Know About Teaching Reading!

Be aware of the idea of phonemic awareness, which is the perception of individual sounds of words – that’s what helps unlock the code.

Also be aware that phonics actually has two meanings:

- I like to use the one that means the sound-symbol relationships of the squiggles on the page, certain spellings. So “I-G-H” in “light” is the sound /i_e/ and the “C-H” in the word “chick” is /ch/ and the “I” in “chick” is /i/. That’s phonics information.

- Another definition of phonics is just any approach to teaching how to decode that emphasizes this phonics knowledge.

That’s kind of where we get into tricky waters because phonics has dual meanings.

Traditional phonics approaches, the teaching of decoding, emphasize a print viewpoint on written language without the emphasis on phonemic awareness.

To the advanced reader phonemic awareness and phonics are so intertwined, that they are almost one in the same.

For beginners, they’re not at all there yet. They don’t know that /a” is “a” and they don’t know that when you say /c/ /a/ /t/ you’re saying “cat.”

That doesn’t come naturally to anybody, until they start to become a reader.

The code unlocks this ability to perceive those sounds and vice versa.

So again, if we could just start all of our kids with building words, really simple words with tiles on a board or on the table we can form this connection or mapping for children.

“Let’s build the word ‘map.' What do you hear at the beginning of the word mmmmaaaap?”

That’s the phonemic awareness part.

Then the phonics piece of knowledge in the same activity… that’s what they need to know to be able to attach each sound to the little squiggle on the page.

When we teach these skills in tandem, children realize what researchers call the alphabetic principle, that our written language is code for sounds.

And that can happen easily with a three, four, or five year old with word building activities.

And after that we give a few letters like “m” “a” “s” “p” “l” and “t.”

“Oh, you have ‘sat.' Let’s change it to ‘sit.'”

And then “sit” to “sip” and “sip” to “lip” and to “lap.”

There are other things we consider to make these connections easier for students and more likely to stick.

Check out our Ultimate Guide to Teaching Blending Sound in Words for more about nuanced considerations around word choice.

Techniques Transfer to Writing, Too!

My hosts wisely point out the high value of this to writing.

And it’s so true!

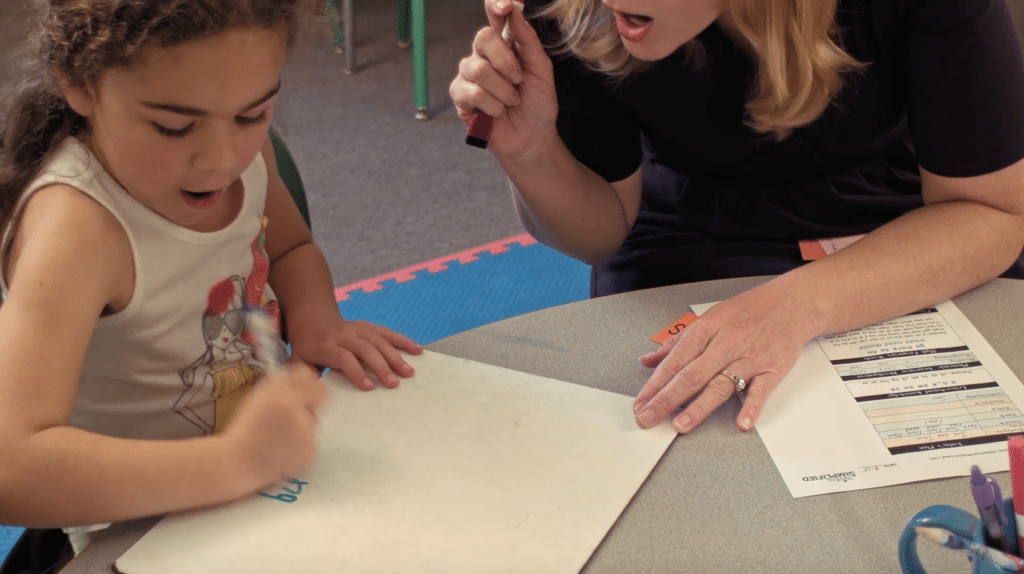

With Reading Simplified we only teach a handful of core word work activities: Switch It, Read It, Sort It, and the fourth one is pivotal!

We plan for it in almost every lesson, and we call it Write It.

It is simply dictation, except that it’s really important for the child to say the sound as they write the corresponding letter or letters.

That means that if it’s a two letter grapheme like “ai” as in “rain” or three letters for the /i_e/ in the word “light,” she’s going to say the sound the whole time she writes that combination of letters.

As much as possible we try to have as much writing time with real hands and fingers as possible instead of writing on a screen.

On the other hand,

For the earliest kids, we use letter tiles as a scaffold for a while because they aren’t able to or haven’t yet been taught letter formation.

They can still access the code though!

So we use tiles as a scaffold for a short season to get them into the stage where they’re going to be more likely to write.

We also keep digraphs and double letters on tiles together so children can change “will” to “wish.”

As soon as children are able to get the concept and writing doesn’t cause massive slowdowns, we would have them do the same activity on dry erase boards.

We actually know that learning letter sounds is facilitated the most by writing them.

Typing or moving letters in cards is not as effective as learning them with the actual motor production.

If you can get fluent with writing all of your letters and writing words, you become more fluent with reading too.

My Take on Invented Spelling

When educators shy away or look down on invented spelling, I think they are likely reacting, against an approach where in the situation children are encouraged to use invented spelling and then it’s never checked.

That situation is not ideal.

And some educators shy away from checking and correcting, because they feel like correction is a painful process.

But writing and spelling correction doesn’t have to be a painful experience.

When they’re young and just learning, I actually expect children after several weeks or months of instruction to be spelling almost everything that is predictable with a short vowel accurately.

If he writes the word “flash” as “fash,” I can help him turn it into “flash” by drawing attention to the sound he missed by orally drawing out the sound like we do for Build It or Switch It.

If he writes “boat” as B-O-W-T, that’s actually pretty good depending on where he is in other skills and I can offer feedback such as,

“Yes that is the /oa/ sound and that is an /oa/ spelling. This is not the way we spell the /oa/ in “boat.” Here’s how we fix that.”

Feedback for certain types of errors at certain times in a student journey is so important!

If I have a beginning five year old and they want to write a superhero’s name, and let’s say they’ve already written 20 words and it’s been totally exhausting for the child, I might help him fix the word “cat” and “flash,” like my first example.

But I’m just going to let a few things go because there’s no need to nitpick over everything that’s not really their developmental timing.

It’s a rule of thumb I use for reading and writing:

We try as a teacher or parent to give the least amount of feedback that’s necessary for the child to be successful on his own.

Supporting Your Child's Literacy Journey

So let’s wrap up!

We can stay on the side of science with some really big ideas around reading such as phonemic awareness, phonics, and how they come together to reveal the alphabetic principle to children.

What we do tomorrow in the classroom or at home for a child, how much to teach, and in exactly what order to teach it is still nuanced.

We do know that for phonemic awareness and phonics we need to offer the code systematically — and I would say more rapidly than many traditional phonics programs.

Parents absolutely can support their children in playful ways to gain the foundational skills they need to be successful and push their vocabulary and background knowledge forward through read-alouds and repeated reading.

Write and Say is powerful in both reading and writing instruction.

Opportunities for feedback in both reading and writing are essential!

I hope you’ll take a look at many of our complimentary resources at ReadingSimplified.com and our youtube channel!