Most learning to read programs isolate reading subskills, such as oral phonemic awareness or letter-sound knowledge, into separate lessons. But the science of how the brain learns to read suggests that children learn to read by connecting their oral language systems with the new orthographic (or print) information. When we integrate multiple reading sub-processes in just a handful of activities, we are more likely to be efficient and effective.

In this 3rd installment of our Science Shorts series, we will consider how science can be misinterpreted when it comes to practice. Let's examine the specific case of phonemic awareness and how different interpretations of the science could lead us in different directions. [If you missed our 1st Science Short “Do You Believe What the Science Suggests?, head here or head here for our 2nd Science Short “Decoding Begins with the Alphabetic Principle.”]

Choose Your Own Adventure with this article…

- Watch the video below to discover how integrating multiple reading subskills may yield better student outcomes. That may be all you want to attend to if you're busy. Keep this Science Short, short. 😉

- If you'd like more explanation, read the following immediately underneath the video.

- AND/Or, then scroll down for video examples using core Reading Simplified activities that put this principle into action.

- [Die hards can read the PA + Print research analysis at the end!]

Science Shorts #3-Integrate; Don't Isolate Reading Subskills

Scientists Pick Apart; Educators Put Back Together

As the Science of Reading movement picks up speed, many more teachers and leaders are, thankfully, digging into the mammoth research project that is how the brain learns to read.

As we learn more of what That Other World has been up to, it's important for teachers to understand that some scientific projects involve breaking up aspects of a process in order to better explain that process. However, an experiment that shows how one element causes another may not be the scientists' declaration that “this is how to teach in the classroom.”

Rather, elements in a process have to be isolated in the experiment in order to truly attribute change or significance to that particular element. For instance, most drug experiments just add the 1 drug to the experimental group in order to test safety and efficacy. When they add multiple drugs or supplements or lifestyle changes, it gets pretty messy to interpret what caused what.

The Research Example of Phonological Awareness

For example, the research world was kind of shook in the 60's and 70's by the idea that learning to read words was dependent on phonology. Thus began an extensive effort to understand the processes better:

How did phonological awareness develop?

Do children with weaker phonological processing have a harder time learning to read?

Was this relationship causal?

Bi-directional?

What are the various elements of phonological awareness? etc…

As early as 1983, a landmark study by Bradley & Bryant found that by teaching sound categorization to prek kids resulted in reading and spelling benefits even 4 years later. They expanded the experiment, however, to also teach one sub-group of children letter-sound knowledge. They concluded that

“This suggests that training in sound categorization is more effective when it also involves an explicit connection with the alphabet.”

But one study alone doesn't make scientists happy about demonstrating causality.

Another influential study by Lundberg, Frost, and Petersen in 1988 just provided Danish preschool children with 8 months of oral only phonological awareness activities (aka metalinguistic games and excericses). Effects of this training could be observed in reading and spelling in 1st and 2nd grade. The authors note this as the purpose of the study:

“By providing phonemic awareness training before the children had any formal reading instruction, we have attempted to establish the causality in a less confounded setting” (p. 266; italics original).

Wonderful! Getting multiple demonstrations of causality is a pretty big deal!

The translation of this study to direct application in the classroom, however, did not consider the full scope of the research. A preschool intervention to demonstrate causality became a Kindergarten program, Phonemic Awareness in the Classroom: A Classroom Curriculum.

And other programs followed suit creating a separation between phonological awareness and letter-sounds and decoding instruction.

This occurred despite the fact that a widely-cited meta-analysis of phonemic awareness concluded that tying PA with print was more impactful. Bus and van IJenzendoorn (1999) noted,

“The current meta-analysis also shows, however, that a purely phonological awareness training such as the thoroughly replicated Lundberg program [note: see study above] is less effective than a program such as Sound Foundations, which includes a letter training, not only in terms of reading skills but even in terms of phonological awareness itself“

(p. 412; note & bolding added).

They go on to conclude,

“The results also show that reading skills are stimulated more by a phonemic training including letter or reading and writing practice than by purely metalinguistic games and exercises” (p. 413).

Yes, oral-only phonological awareness activities have been demonstrated to make a difference. But when one looks at the full research base on phonemic awareness, one sees more efficient and effective gains when phonemic awareness is combined with letter-sounds (as mentioned above in the 1983 quote and summarized in the National Reading Panel and a recent updated synthesis).

In addition, the broader view from the scientific community of how children learn to read suggest that PA isn't an end in itself but rather a means to induce the alphabetic principle. And then good young readers develop good PA as part of the process of cracking our written code.

Thus, I'm suggesting that children do better cracking the written code when we integrate both phonemic awareness and phonics knowledge, among other places we can integrate multiple skills.

[Not everyone wants to take a deep-dive into the phonemic awareness applied research, so I'll save it for the nerdy types like me at the bottom of this article.]

Activities That Integrate Multiple Reading Subskills

In the meantime, let's get practical.

The following activities are core Reading Simplified activities that all fold in several reading subskills simultaneously.

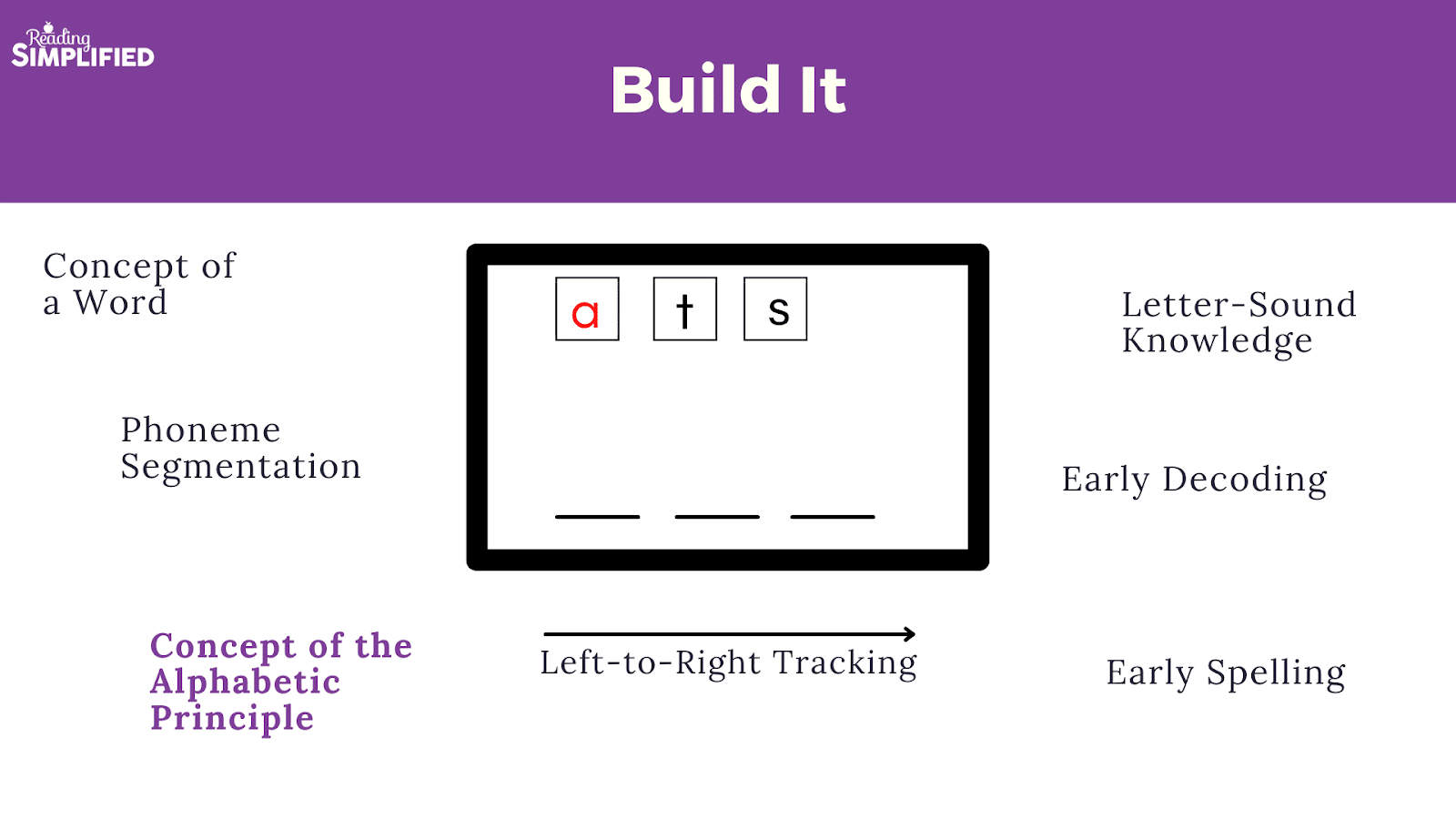

Build It Reveals the Alphabetic Principle & More

Rather than start with teaching all the letter names and/or sounds of the alphabet–as I have suggested here–we suggest starting off with the activity Build It to teach the alphabetic principle.

But as you can see from the above graphic, Build It teaches so much more. See, we can integrate multiple reading subskills simultaneously with simple, fun word building, reading, manipulating, and writing activities!

In the video below, we see a 3 year-old discover the alphabetic principle via a game-like activity we call Build It.

When the teacher draws his attention to the sounds in the word, such as “map,” he's in the early stage of getting the alphabetic principle.

But he also needs to have a hint of phonemic awareness and letter-sound knowledge to really cement the concept that our written language is a code for sounds. In the video snippet above, he's not a master yet by any means, but he's well on his way since he has demonstrated partial:

- understanding of the alphabetic principle,

- phonemic segmentation of 3-sound words,

- letter-sound knowledge (just consonants and a short vowel for now), &

- left-to-right tracking.

Build It, like other Reading Simplified word work activities, incorporates multiple reading sub-skills simultaneously–from the beginning. This integration of skills makes more sense to children…

…and even dramatically accelerates the early learning process!

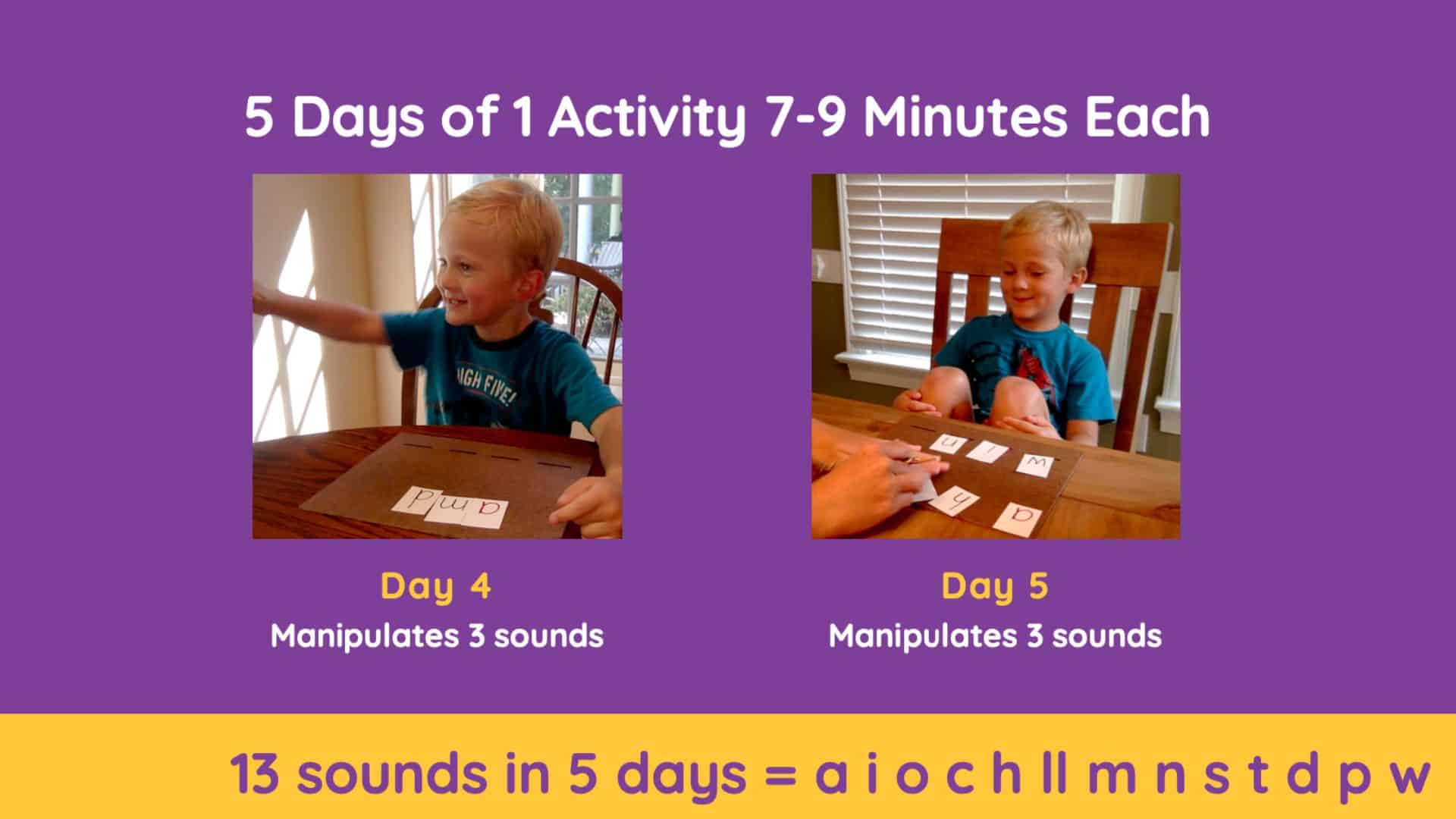

P.S. If you want to see how confidently and rapidly a young child can grasp the alphabetic principle (and other early reading sub-skills), watch this 5-day mini-experiment of just 1 activity a day for about 8 minutes with a 4 year-old….

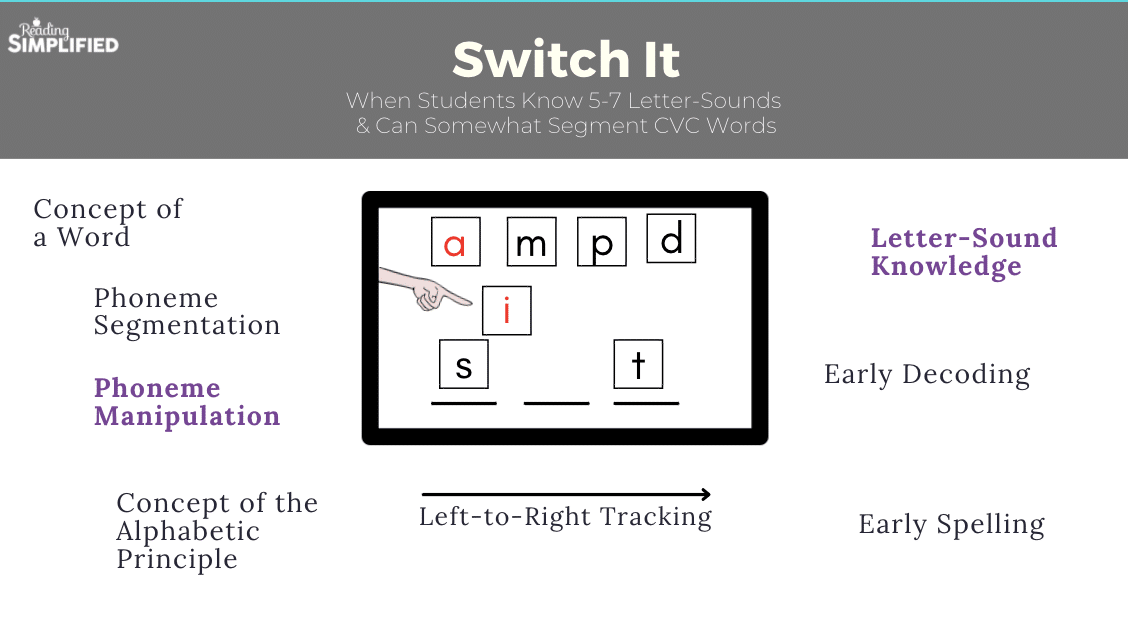

Switch It Facilitates Alphabetic Coding Excellence

Once a child knows about 5 to 7 letter-sounds and can segment the initial and final sound in a CVC word, she is ready to advance to Switch It and drop Build It. Switch It is the most powerful reading activity I have ever observed.

In mere minutes, most students show improvements in their processing of grapheme (letters and letter combinations) and phoneme (individual sounds) correspondences in the context of real words. They develop stronger and stronger mental linkages to support alphabetic coding–learning to decode and encode (spell) words.

Like Build It, Switch It isn't just a 1 trick pony, either. See all the reading subskills that one can address with just Switch It….

Switch It Unlocks the Code for a Struggling Student in 5 Days

See the in's and out's of Switch It in the example below and also notice how rapidly a once struggling kinder student leaps ahead. As part of a mini-experiment, I did just 8 minutes of Switch It per day for 5 days in a row to show the power of putting all these reading subskills together in 1 activity.

Did you see that?

This child who had been identified by his kindergarten teacher as struggling learned 13 letter-sounds in 1 week. He also learned how to segment and manipulate words with 5 sounds in them! Initially, he couldn't even hear the medial vowel in a CVC word.

We want the same for your student(s) even though that reading program you've probably been given would have you spend weeks doing oral-only phonemic awareness, separated from letter-sound instruction and only 3 months later beginning to read, write, and play with words.

If you have older struggling readers, this activity is still super helpful. Here's the first lesson with a 6th grader reading at the 4th grade level. We've already moved to nonsense words to really challenge her alphabetic coding system:

She only needed a little tweak here or there but you can see how greater care with phonemic processing and letter-sound knowledge was the focus. This will pay off with multisyllable words especially. (Want to see more of a lesson for an older struggling reader? Scroll down on this page.)

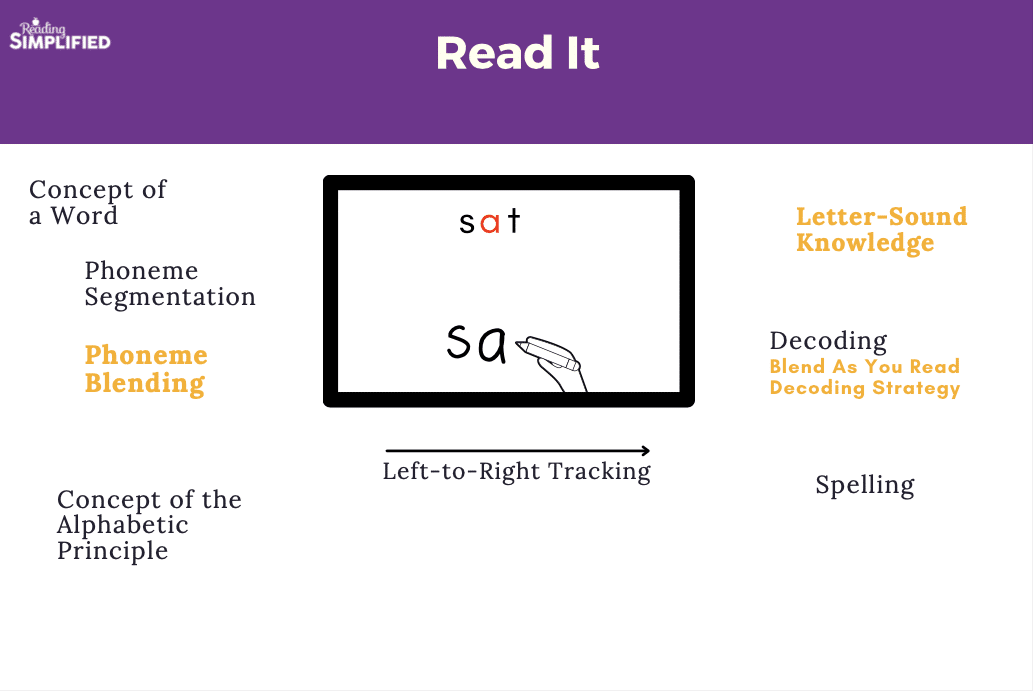

Read It Teaches Effective Decoding Strategy

Whether our students are at the Build It or Switch It level, we usually pair one of them with Read It too. With Read It all the pieces start to come together and the child learns how to read real words.

Blending, initially, is our number 1 goal for Read It, but as you can see, it also accomplishes several other reading subskills like its sisters above…

Let's see Read It in action, shall we?

Notice how the young kindergartner employed the Blend As You Read decoding strategy, which I go in depth on in the Ultimate Guide to Blending Sounds here.

Did you see how he was tying orthography and phonology, print and sound, reversibly? First he decoded the word; then he encoded (spelled) it.

Like in the other Word Work activities above, during Read It the child is being guided to make connections between his language system and his budding system of word reading.

Other Core Word Work Activities That Integrate Throughout

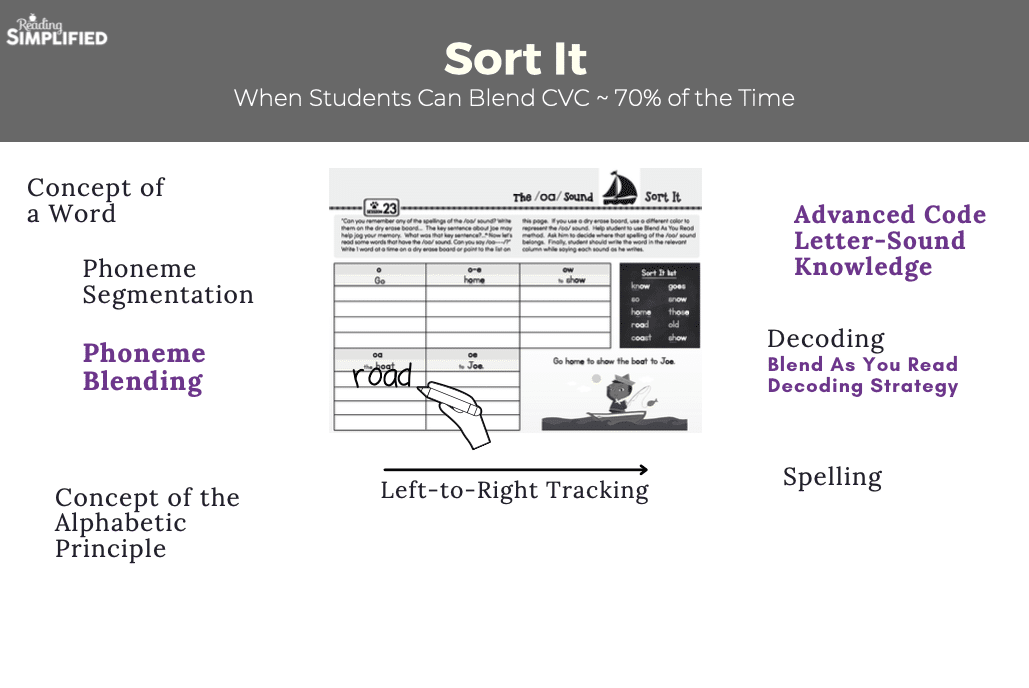

Briefly, after a child can blend CVC words about 70% of the time, the teacher can mostly fade Read It and replace it with Sort It.

Sort It is an efficient activity for revealing more about the advanced code, such as long vowels and diphthongs. We let the child know she's reading words that all have the /oa/ sound, for instance. Then she reads them, sorts them, and Write & Says each sound.

It's easy for children to understand when the info is organized! Learn more and get a free sample Sort It packet here.

In the image below you can see again multiple reading subskills being taught through Sort It…

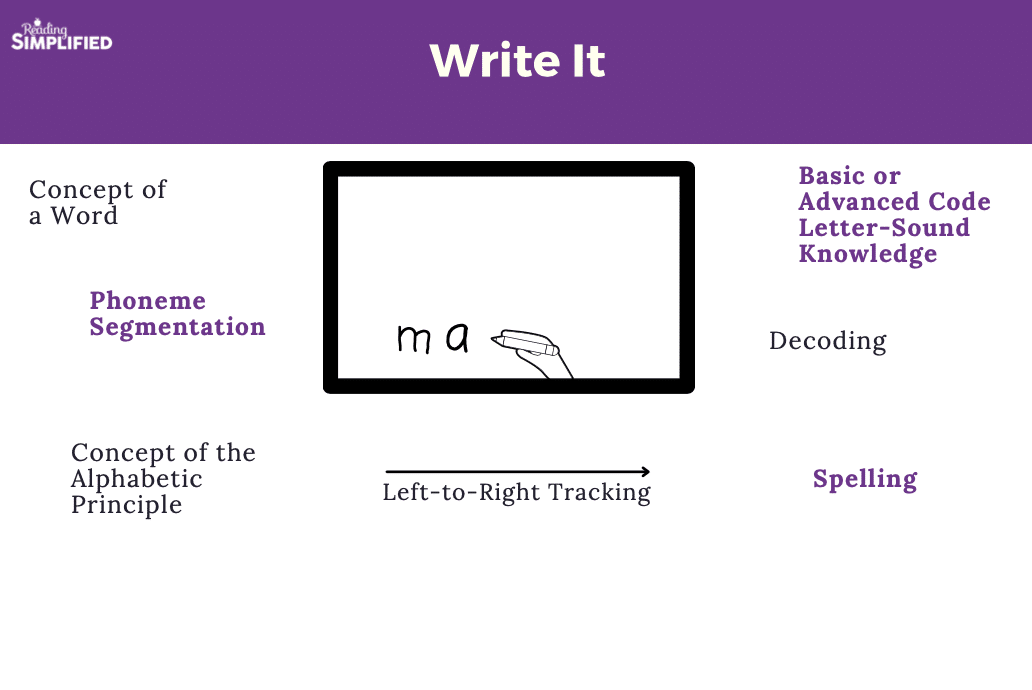

Our final core Word Work activity is Write It in which the teacher dictates a word, phrase or sentence to the student. The student Writes & Says each sound. Then the teacher coaches her on changes if spelling or phonemic errors were made.

Write It tests the mind of the developing reader and speller so it's a great tool for more and more practice as the child develops in her decoding and spelling knowledge.

As you can see, across the activities Build It, Switch It, Read It, Sort It, and Write It, we can help children gain insight into how our code works…while we are developing a variety of reading subskills such as phonemic awareness or letter-sound knowledge.

No need to isolate each component of reading!

Keep reading if you want to understand more about the research base I'm reading to feel confident that teaching reading is better when one begins by connecting PA and print.

OR, if you've seen enough to move forward, I'd love to know what you think? Please skip down to the bottom and share your comment with me and others!

The Case for Integrating PA with Print

It has been doctrine for at least 20 years that phonemic (or phonological) awareness must precede print instruction. In other words, one must help a child hear individual phonemes in words before one can expect the child to read, spell, or manipulate sounds in words.

We've lost a lot of ground with students because of this belief. I have a lot of reasons but I'll just list 3:

#1 The Science of How the Brain Learns to Read Directs Us Towards Making Connections

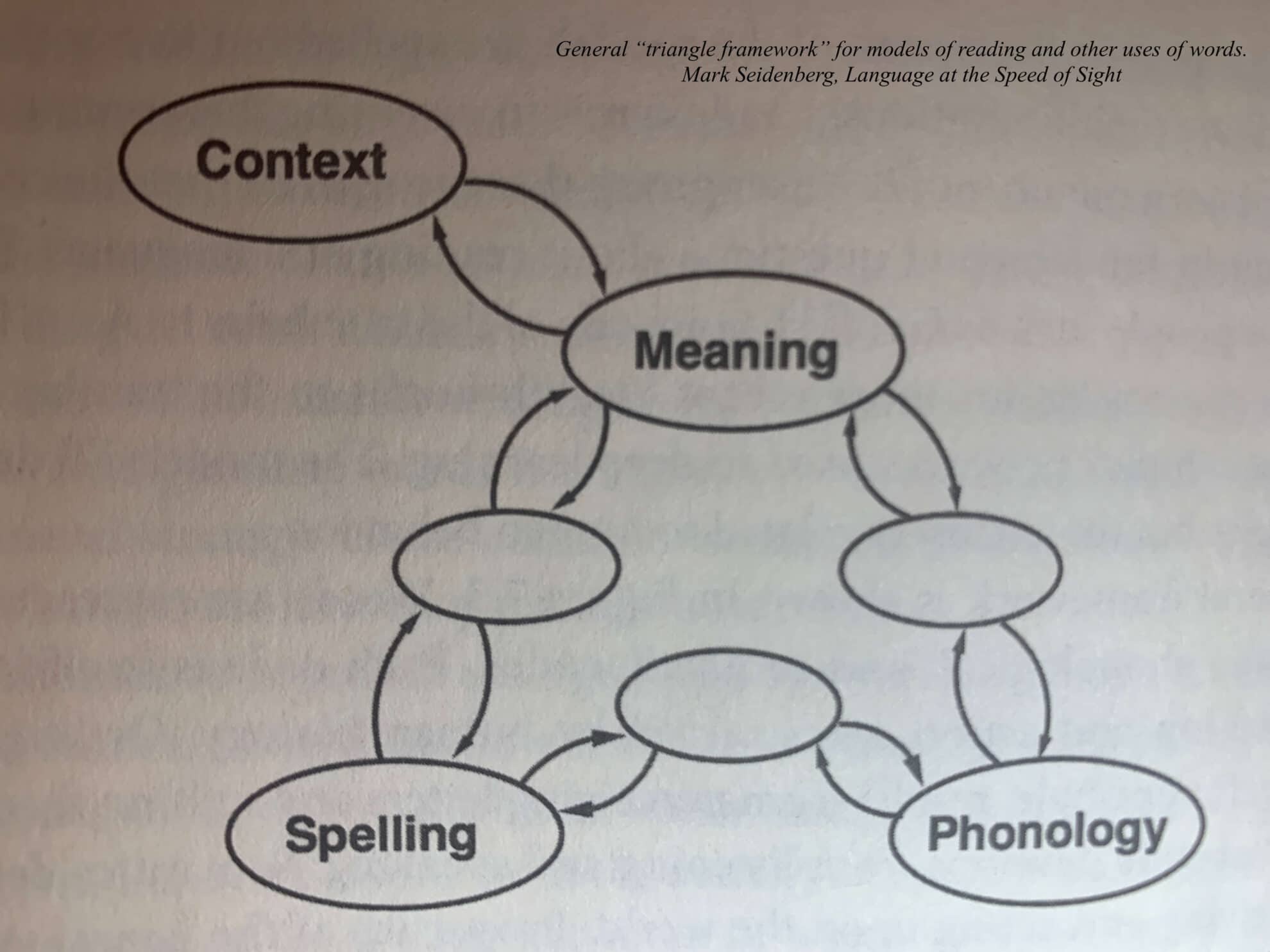

First, theory and research teaches us that the brain learns to read through connections among the existing semantic and phonologic networks with that of the developing orthographic (spelling or print) network, as in the Triangle Model of Reading.

The preschool or kindergarten child has amazing well-developed Meaning and Phonology networks already. But they don't get the code…the Spelling system.

How do they acquire the Spelling network (aka learn to read words)?

As mentioned early in this article, a little tiny dose of phonemic awareness and letter-sound knowledge was sufficient to induce the alphabetic principle. Then practice reading is our next best way to develop the entire Word network. We know that phonemic awareness is bi-directionally related to reading (e.g., Perfetti, Beck, Bell, & Hughes, 1987 or Wagner, Torgesen & Rashotte, 1988).

In other words, children need a little info about how our code works and then they need to practice reading words. Along the way they develop stronger and stronger phonemic awareness because it's the glue that allows words to stick.

The neuroscientist Mark Seidenberg, in the book Language at the Speed of Sight, explains this process well. For instance, he writes,

“It should now be clear why becoming alphabetic is a major hurdle that requires instruction, feedback, and practice. The child has to think phonemically, which involves both phonology and orthography, and learn arbitrary cross-modal associations between graphemes and phonemes….

Although it is called the alphabetic principle, the term is a rather high-level description of behavior that isn't much like learning a rule or other broad generalization. Children do not go from staring blankly at printed words to the realization that they consist of graphemes that correspond to phonemes, resulting in the wholesale reorganization of orthography and phonology. The developmental sequence instead involves accumulating knowledge of the statistical structures of orthography and phonology and the mappings between them” (2017, p. 120).

Insight about how our code works gets the young reader started but the bulk of learning to read is done mostly by getting stronger and stronger networks between graphemes and phonemes in real words. The more we separate PA learning from print, the more opportunities for looking at print we've lost.

Relatedly, adults who are illiterate do not acquire phonemic awareness. Phonemic awareness usually only develops in the context of learning to read. Let's do more reading as we coax our students' developing PA skills then!

This really doesn't do justice to the research of how reading develops but I hope it offers a flavor and more things to pursue.

#2 Experiments Show Faster Outcomes When PA Is Connected to Print

In 2000, the National Reading Panel's phonemic awareness conclusions noted that students had higher achievement when PA was connected to print. They weren't the first to point this out. An earlier meta-analysis by Bus and Van IJzendoorn in 1999 that I mentioned above concluded the same thing.

But these findings were mostly ignored in mainstream practice.

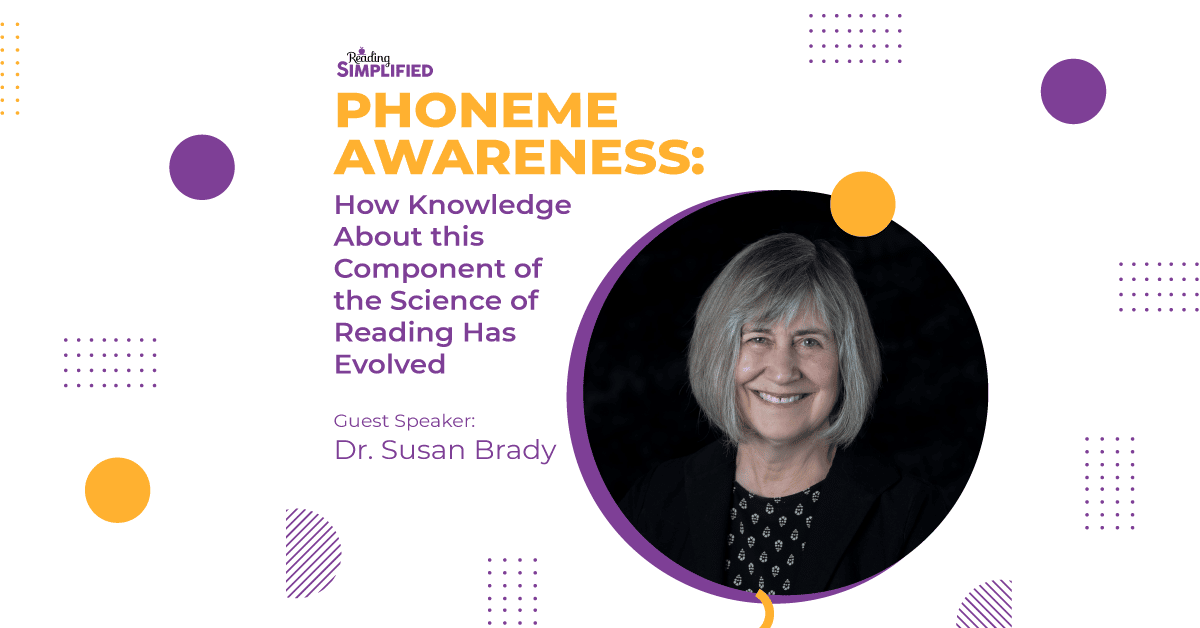

More recently, former researcher at Haskins Laboratories and Emeritus Professor D. Susan Brady has persuasively presented the case from research since 2000 about PA. Brady concludes,

“Phoneme awareness instruction should be integrated with letter instruction. Teaching phoneme awareness for a set of individual phonemes should be followed by instruction in the corresponding letter(s) when phoneme awareness as a listening activity is well established for those phonemes. This order helps clarify for students that phonemes are elements in spoken words and that letters are how those speech sounds are represented in writing (i.e., the alphabetic principle). As discussed earlier, the NRP report and subsequent studies have confirmed that linking phoneme awareness with letter-sound knowledge strengthens the application of phoneme awareness for improved reading and spelling performance.”

Brady includes lots of great citations to back this claim up.

The IDA, International Dyslexia Association, also just recently released a fact sheet, “Building Phoneme Awareness: Know What Matters,” that is in tight alignment with Brady's paper above.

Here is a snapshot of their conclusions:

Not convinced?

Watch what reading scientist affiliated with Haskins Laboratories, Dr. Susan Brady, demonstrates about the research benefits of linking PA with print in this presentation we hosted last year:

Over 7,000 teachers and parents have watched this presentation either live or via the recording, so you know it’s worth watching right now or at least bookmarking!

Sample Experimental Studies of PA with Print

Here are just a few experimental studies that should give one pause when you read that children must have phonological awareness precede letter-sound and decoding instruction:

Preschool Children with Speech Deficits Benefit from PA & Letter-Sounds Integrated

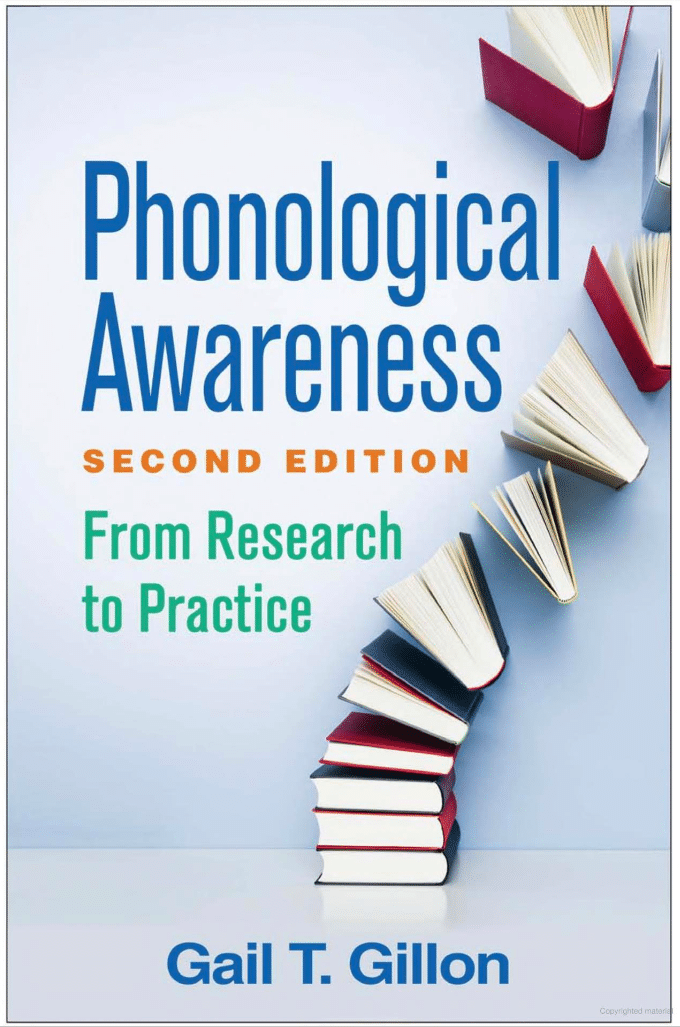

Gail Gillon, a professor in New Zealand who wrote the textbook, Phonological Awareness, which is in its 2nd edition, ran an intervention with preschool children who had been identified as at risk for reading difficulties because of their speech deficits. After about 25 group and individual sessions of activities to facilitate phoneme awareness and letter knowledge, the children were tested later at age 6.

These young students who showed high risk for reading difficulties were at average levels or above in reading and PA measures. Speech intelligibility, too, had improved.

Dr. Gillon concludes,

“The data provide evidence to support the clinical practice of integrating activities to develop phoneme awareness and letter knowledge into therapy for 3- and 4-year-old children with moderate or severe speech impairment” (p. 308).

That's a pretty bold finding considering that most contemporary reading programs seem to think that typically developing kindergarten students can't handle this!

Whole School PA and Phonics in Preschool Yields Growth in PA and Decoding

In 2019, Carson, Bayetto, and Roberts reported the results of their intervention with ninety 4 year-olds in Australia, including a minority with SLD. Classroom teachers delivered phoneme-level instruction coupled with letter-sound instruction for just 10 weeks for a total of about 13 hours of instruction.

Afterwards, typically developing intervention children did significantly better in PA, letter-sound knowledge, and early decoding, whereas the children with SLD only performed higher in PA and letter-sound knowledge.

Again, we see an example from an experiment that demonstrates that even young children can handle the integration of phonemic awareness and phonics knowledge!

"In line with the phonological linkage hypothesis, we have shown that an effective way of improving reading skills involves a joint approach that integrates the training of phono- logical skills with the teaching of reading. Spending an equivalent amount of time concentrating on either component in isolation (reading or phonology) is less effective" (p. 52).

Hatcher, Hulme & Ellis, 1994

7 Year-Olds Struggling with Reading Gain More with Phonology + Reading

Leading UK reading researchers (Hatcher, Hulme & Ellis, 1994) tested 4 matched groups and delivered different interventions across 20 weeks:

- Phonology Alone

- Reading Alone

- Reading with Phonology and

- Control.

The Reading with Phonology outperformed the rest of the groups in reading and spelling. The authors conclude,

“In line with the phonological linkage hypothesis, we have shown that an effective way of improving reading skills involves a joint approach that integrates the training of phono-logical skills with the teaching of reading. Spending an equivalent amount of time concentrating on either component in isolation (reading or phonology) is less effective” (p. 52).

#3 Teachers of Reading Simplified and Related Integrated Approaches Report Faster Growth

I have to admit that I am biased towards believing that PA integrated with phonics from the get-go yields better results–and not just because of the scientific theory or experiments.

I've been teaching beginning and struggling readers of many ages to read for over 20 years and they learn how to decode very, very quickly. Sure, those with severe dyslexic difficulties may take a while to get to fluency, but even they figure out how to decode in hours, not year. And most students figure out how our code works and get to grade level or read real books in just 12 hours of instruction.

This radically-short time frame was first reported by the developers of Phono-Graphix in 1996 in the Annals of Dyslexia. In just 12 hours, 87 students who had reading difficulties made standard score gains of over 13 on word identification and over 19 in word attack. As Dr. David Kilpatrick points out in his Essentials book, these gains far surpass the gains of mainstream programs, such as Wilson or Leveled Literacy Intervention who see standard score gains of only 1 to 4.

All this in 12 hours!

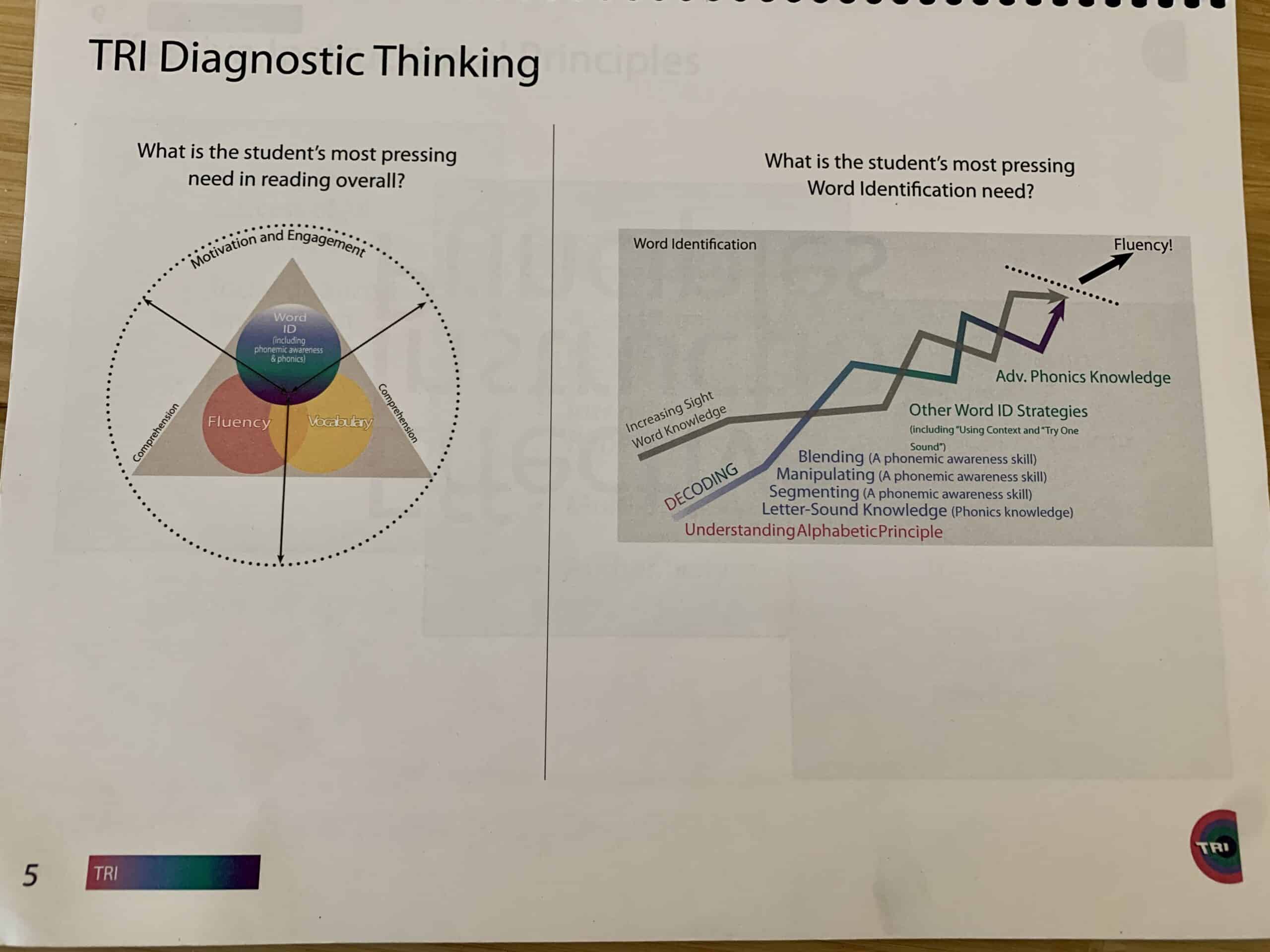

I led the development of the Targeted Reading Intervention (TRI) and packaged into these core elements of connecting phonemes and graphemes from the beginning with K-2 struggling readers in rural, low-income communities. That program has been studied numerous times in clinical trials with repeated success for reading.

I got to see teachers who had struggled mightily in helping struggling readers unlock the code for their students with the TRI. Much of this success I attribute to the clear connections we helped teachers make between graphemes and phonemes from the beginning of instruction.

With my current project Reading Simplified, we literally hear every day how a teacher and a child or children's lives are being changed by our method that integrates multiple reading skills with each activity.

For instance, a literacy clinic owner just shared this with me:

“I have been trained and used the Orton-Gillingham approach for years, but always questioned that there had to be a more effective and streamlined way.

After finally doing some searching, I found Reading Simplified and immediately knew I had to try, so I took the training.

In the middle of last year, I talked with 3 families that I was tutoring 1:1 using the OG method about it, and they agreed to allow me to give it a try with their kids.

Their kids were making progress, but it was incredibly slow.

With Reading Simplified, each of those 3 kids made anywhere from 1-3 years growth in about 5-6 months' time.

I'll never look back to OG. Switching to Reading Simplified was one of the best decisions we've made.”

At a time when US NAEP reading scores come back the lowest in 20 years, we all need to be looking at more efficient options. Approaches that build connections among phonemic awareness and phonics knowledge from the beginning, like Reading Simplified, are much more likely to accelerate student growth that we so desperately need.

We're not the only ones, either.

"With Reading Simplified, each of those 3 kids made anywhere from 1-3 years growth in about 5-6 months’ time. I’ll never look back to OG. Switching to Reading Simplified was one of the best decisions we’ve made."

Check out EBLI. Or Sounds-Write. Or Literacy Hill. Or Phonic Books.

Extra brownie points for hanging with this idea for so long. But I'd love for it to be a 2-way conversation…

Every bit of evidence and experience supports

integrating multiple reading subskills. The supreme gift you have given, Marnie, is simplicity!

In four hours of formal teaching, my non-reader has moved from no phonemic awareness or knowledge of letter sounds to now building CVC’s . writing CVC’s and involved in Guided Reading with joy

Amazing!! We’re so glad to hear this Merran. Congrats to you and your joyful reader!