When Emily Hanford tipped over a domino with her powerful audio documentary "Hard Words," the field of reading education became startled out of our status quo.

Now I bring you word of just how far this shaking has come: two well-respected balanced literacy leaders have recently

- looked into the reading research;

- admitted shifts toward the science are needed; and then

- presented a persuasive case for making simple adjustments to

mainstream balanced literacy practices.

Yes, Dr. Jan Burkins and Kari Yates recently released their stunning new book, Shifting the Balance: 6 Ways to Bring the Science of Reading into the Balanced Literacy Classroom.

Their book is a rare example of laying down a bridge to allow teachers who are trained in balanced literacy to cross over and hear better the perspective of those waving the Science of Reading flag. They write,

What do you think? Do these shifts seem like something that you could implement in your reading instruction?

Do you see a way forward for balanced literacy teachers to adapt instruction based on contemporary reading science WITHOUT having to overhaul their entire instructional practice? ????

My Review of the Shifting the Balance Book

Please do watch the video above to hear about the remarkable journey that Jan and Kari underwent to create this excellent primer on K-2 reading instruction. When you do, I hope you'll hear my admiration and enthusiasm for this book--Shifting the Balance: 6 Ways to Bring the Science of Reading into the Balanced Literacy Classroom.

[A token percentage of each sale can support the work of Reading Simplified at no additional cost to the buyer.]

Along the way, you'll also receive great professional development and a book preview on 2 of their recommended shifts, regarding

(a) the connection between language and reading and

(b) an improved technique for learning so-called sight words.

I'd also like to put down in print a few of the highlights that thoroughly impressed me about Jan and Kari's accomplishment....

#1 Burkins & Yates' Book Truly Builds a Bridge

First, in the decades upon decades that the reading wars have been raging, few authors or leaders have taken on the perspective of the other "side" in their writing or speaking. It has been rare to hear a literacy leader who embraced whole language (or later balanced literacy) understand and interpret the phonics philosophy accurately, and vice versa.

Phonics is often caricatured as "drill and kill" while balanced literacy is reduced to as "just guessing at words." These extremes trigger immediate defensiveness in most of us humans.

As a result, many times these communities have missed opportunities to find sources of commonality. However, the perspective-taking and gentle language in Shifting the Balance defy these patterns of history.

Instead, Kari and Jan talk honestly about the tensions they felt in re-considering old practices in light of the science. And they interpret the chasms--that many people in the reading wars have assumed to be impassable--with kindness and gentleness.

Here's an example from the introduction of the accurate yet middle-ground approach the authors adopted:

Through it all we found, as have others, that the experimental research on reading isn't completely consistent or irrefutable. Furthermore, research is even less clear or consistent when it comes to the nitty-gritty nuances of classroom instruction, such as the exact order for introducing letters and sounds. However, the experimental science that establishes how the brain learns to read is far too comprehensive and too robust to disregard.

Jan Burkins & Kari Yates

Shifting the Balance: 6 Ways to Bring the Science of Reading into the Balanced Literacy Classroom

The authors build bridges in other ways. For instance, each chapter begins and ends with a story of a balanced literacy teacher who has doubts about his/her practices and is open to change. The insights of each chapter's shift leads the teacher to adapt his/her practice, enfolding in the new research-based learning. Jan and Kari are considerately showing the way forward in these vignettes.

For instance, in the chapter, "Reimagining the Way We Teach Phonics," we follow Ms. Lin's transformation. At the beginning of the chapter, she begins with engaging ways to teach the "ch" spelling but realizes that the only opportunity for her Level D small group to practice that spelling is once on page 6. P.S. This is a massive opportunity for change from mainstream practices.

The authors write,

"As her children transition to music, Ms. Lin recognizes familiar but nagging concerns about her phonics instruction. Some students appear to be less engaged week by week, and there seems to be a disconnect between her whole-group phonics instruction and students' application of phonics principles during guided and independent reading."

Then we learn about 5 misunderstandings in the teaching of phonics and a different direction to take from the science:

Finally, the phonics chapter ends with a description of the adaptations that Ms. Lin has enfolded. We read,

"For a long time, Ms. Lin has worried that when it comes to application of phonics, her kids were all over the map...."

Finally, during interactive writing, Ms. Lin sneaks in some authentic practice of CVCe words. She tells the students (a mostly true) tale of a recent bike ride. Together they construct and write 'Ms. Lin rode her bike to the lake. She saw a snake along the path. Yikes!'"

These anecdotes are just some of the ways in which Jan and Kari build a bridge from mainstream balanced literacy practices to those more informed by the science of learning to read. In social media circles, I've seen some scoff at these accommodations, as if it's a sign of weakness that a teacher would need "coddling." Such a mindset ignores the entrenched patterns of behavior from decades of reading wars. It also ignores the science of how difficult it is to change a person's mind.

From their presentation in the Science of Reading--What I Should Have Learned in College Facebook group, Jan and Kari tipped me off to the importance of this vantage point--especially with a hot potato topic like beginning reading! They drew attention to the insights of organizational psychologist Adam Grant who recently published, Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don't Know. Grant argues that intellectual muscle-building occurs when we embrace the thinking of those who differ from ours: "This is an interesting opportunity to learn..."

When we try to change a person’s mind, our first impulse is to preach about why we’re right and prosecute them for being wrong. Yet experiments show that preaching and prosecuting typically backfire — and what doesn’t sway people may strengthen their beliefs. Much as a vaccine inoculates the physical immune system against a virus, the act of resistance fortifies the psychological immune system. Refuting a point of view produces antibodies against future attempts at influence, making people more certain of their own opinions and more ready to rebut alternatives.

Adam Grant, Author of Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don’t Know

The NY Times, 1/31/21

Have you had that experience of sharing science with others and it backfired?

Yup.

Therefore, positioning new ideas from reading science from the worldview of the teacher with a balanced literacy background is a savvy way to present controversial ideas. When we don't try that tack and we just state the facts of the science without perspective taking, we should expect our attempts at persuasion to fail. Jan and Kari are leading the way here and, if we want change, we should probably listen!

#2 Shifting the Balance Hits the Bullseye

While many things about how humans learn to read words are now stunningly clear from 50+ years of research, scientists haven't handed us an instructional manual from on high with precise recipes for daily instruction. ???? So, in our enthusiasm for the Science of Reading movement, we must be careful to not over-extend claims about programs that come from the systematic phonics tradition. Shifting the Balance balances these tensions expertly....

Jan and Kari have carefully plucked out 6 targeted shifts and a related 27 misunderstandings from contemporary balanced literacy instruction that they are setting aright. But the entire apple cart of balanced literacy needn't be overturned, as many of its practices are research-based as well, such as drawing upon children's background knowledge, engaging them with interactive read alouds, and connecting their writing with their own lived experience.

I was amazed as I read this book how laser-tight these misunderstandings are: Shifting the Balance zeroes in on exactly the most flagrant errors in mainstream balanced literacy practices. They hit the bullseye with the needed changes they targeted! I'm just so impressed that literacy leaders immersed in the balanced literacy community for so many years could study the research that Emily Hanford's "Hard Words" audio documentary stirred in 2018 and then already synthesize the flaws so efficiently and persuasively.

The book's directives are not just rehashing old teacher guides to phonics instruction, either. Rather, Shifting the Balance incorporates cutting-edge research ideas to yield actionable practices, such as the topics of set for variability and integrating phonics with phonemic awareness. They even included an influential paper from Susan Brady from 2020 that came out just months before the book was published! Indeed, apt references to a huge variety of research articles are sprinkled generously throughout the text.

The Example of Phonemic Awareness

For instance, even though most reading programs isolate phonemic awareness from phonics in the early days of instruction, Jan and Kari point out how essential phonics and phonemic awareness are together. (We've known this since the National Reading Panel report in 2000 but it's rarely incorporated into early reading programs and interventions.) They write:

So, learning the letters and sounds alone is clearly insufficient for success in learning to read! Helping students discover (alphabetic insight) and deepen their understanding of the alphabetic principle, therefore, requires thoughtful emphasis on phonics and phonemic awareness--and their relationship--as two parallel and reciprocal sides of the beginning reading coin (Castles et al., 2009, Hulme et al., 2012; Miller, 1999).

Jan Burkins & Kari Yates

Shifting the Balance: 6 Ways to Bring the Science of Reading into the Balanced Literacy Classroom

Similarly, they point out that most of our instructional time should be spent, kindergarten and up, at the phonemic level, rather than the more global phonological level of words, syllables, and rimes.

Beginning in kindergarten and continuing through first grade (and even beyond), it is urgent for all students to have consistent opportunities to develop, deepen, and apply phoneme-level skills, such as phoneme segmentation or substitution....Phonemic awareness should be the instructional priority, over phonological awareness tasks.

Jan Burkins & Kari Yates

Shifting the Balance: 6 Ways to Bring the Science of Reading into the Balanced Literacy Classroom

Not only is this how I read the research on early word acquisition, we at Reading Simplified also find rapid learning of letter-sound, phonemic awareness, decoding and encoding when we integrate multiple skills like PA and phonics in the context of words.

What's the big deal, you may wonder? We see so much faster uptake of real reading with this integrated approach.

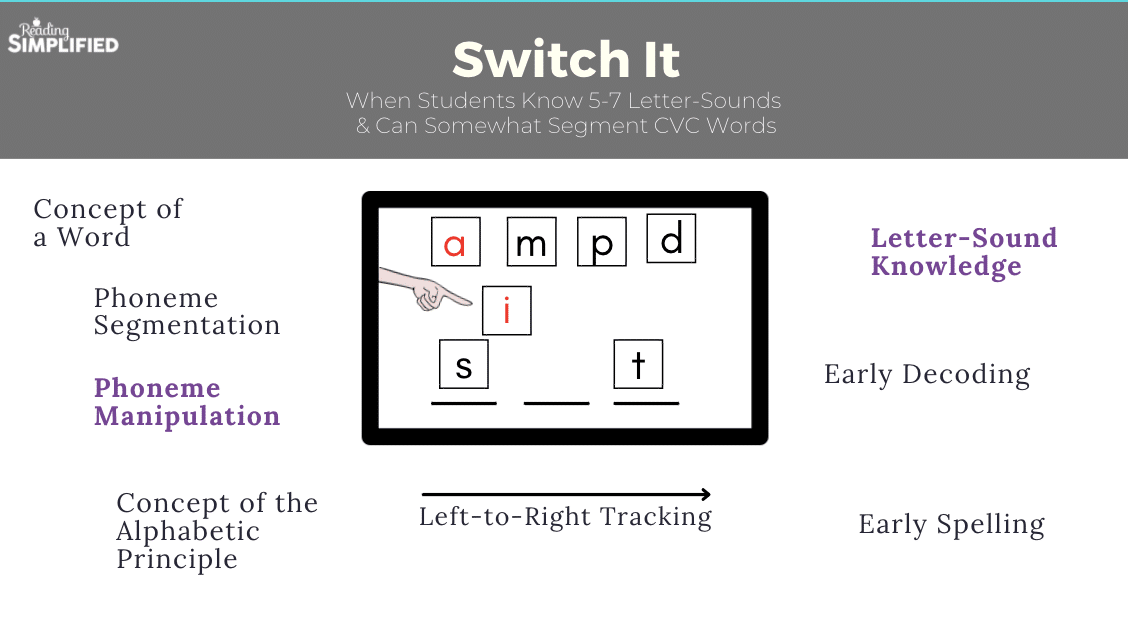

For instance, watch below for a speed tour through 1 preK student's first introduction to how to read words. He does just 8 minutes a day of a Word Work activity that connects phonemes with phonics information--first 3 days of just Build It, followed by 2 days of just Switch It.

By the end of the week, he's learned 13 letter-sounds and is manipulating 3-sound words...with more and more independence! Contrast that with most preK or K programs who would have still capped him at the identifying words or syllables level of phonological development.

The Example of Set for Variability

Throughout the book we also read briefly about the term "set for variability" which has only recently caught steam in research circles yet is rarely discussed in practitioner PD. The term refers to the step in the decoding process that follows after a person has attempted to decode the spellings in a word and discover the actual pronunciation and meaning of the word. Researchers Tunmer and Chapman, who jump started recent research on the concept of "set for variability" define it as "the ability to determine the correct pronunciation of approximations to spoken English words" (2012).

In other words, if a child attempts the word, "down" as /doan/, does she have the skill to adjust her pronunciation to represent the word accurately in terms of its pronunciation and its meaning?

In the last few years, researchers have demonstrated that accurately decoding an unknown word requires at least 2 steps--blending the sounds together and set for variability. Blending alone is not sufficient.

In addition, coaching children to improve their set for variability skill works. This concept about how kids first crack the code for each novel word is important!

- Are we providing our students the necessary skills to be able to manipulate phonemes in and out of words if they don't at first select the correct sound for a tricky spelling?

- Are we giving them enough opportunities to read unknown words in text that allow them to develop greater automaticity with set for variability?

Jan and Kari fold in the concept of set for variability throughout the book, which just impresses me! For example,

But in addition to letter-sound knowledge, there are understandings and skills children must have to actually read. Children must also understand that letters are spoken sounds written down (alphabetic principle), how to blend those sounds and 'make the leap' to a known word (set for variability), and how to use those blended words as a bridge back to meaning (Tunmer and Chapman 2012; Dyson et al. 2017; Elbro and de Jong 2017). Without these skills children can know all their letters and sounds and still not be able to read.

Jan Burkins & Kari Yates

Shifting the Balance: 6 Ways to Bring the Science of Reading into the Balanced Literacy Classroom

Set for Variability & Switch It

Here at Reading Simplified we have found a few pieces of our system support quick uptake of set for variability. First, the multi-purpose activity Switch It, not only builds letter-sound knowledge rapidly, it also provides the child with the ability to manipulate phonemes in and out of words (advanced phonemic awareness). This level of phoneme awareness seems essential to set for variability skill, as moving from a mispronunciation to correct word recognition is both a phonological and semantic process.

Playing around with sounds in words in activities like Switch It paves the way for set for variability, as the skill lies at the intersection of phonological knowledge and semantic knowledge. We call this skill Flex It, though we mean the same thing as "set for variability." Watch how a 5 year-old cracks the code on the word "guess" in the video below, even though her original pronunciation was: /g/ /u/ ...."

Or, notice how an older reader uses the Flex It strategy with the word "patriot" below.

The student didn't know the meaning of the word "patriot" but the sound of the word was familiar. This is a common occurrence with developing readers especially at the multisyllable level--some words that have been heard before are stored in the phonological memory, even if they're not connected yet to semantic memory. With both "guess" and "patriot," the skill of manipulating phonemes in and out of words to connect with a word stored in phonological memory was helpful. The Switch It activity helps build the processing ability to support this skill.

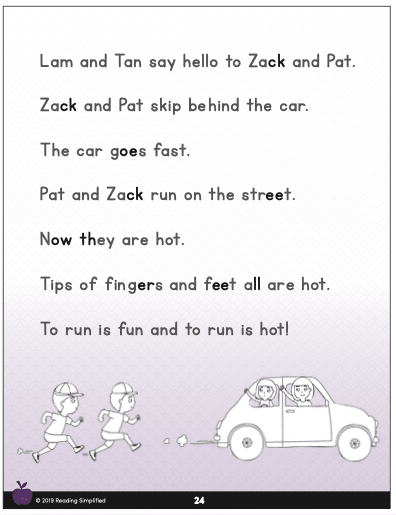

Set for Variability & Mostly Decodable Texts

Another key principle of Reading Simplified is to place beginning and struggling readers in challenging texts, including those that may have phonics spellings the child has not yet been taught before. We call them mostly decodable texts. These are texts for those beginning to understand how to crack the code that do control the words. They include a lot of what's the phonics focus of Word Work instruction (i.e., short "a" and "i" words in the image below), yet they may also have several words that have patterns not yet explicitly taught.

When a child encounters the text below from the Reading Simplified Academy, the teachers' purpose is likely to reinforce blending 3 sound words and reading words with the short "a" and "i" patterns. However, when the child gets to the words, "street," "fingers," and "feet" he has not yet been explicitly taught the "ee" sound or the "er" sound.

The teacher will encourage the child to make an attempt, by Blending As He Reads, a core Reading Simplified strategy. He may be able to deduce that "ee" is /ee/ by making an attempt and read "street" correctly. Or, his teacher may need to provide feedback about the unexpected spelling. A harder cognitive struggle may happen with these words, indeed. However, if a majority of the text is more easily within the child's grasp, he can likely handle this level of challenge. (And level of willingness to face this difficulty varies widely be child.) At this juncture of cognitive struggle with unknown spellings, I think the child is building his set for variability skill more and more, given the opportunity. (These types of reading experiences work best in the small group or 1-on-1 settings where students have many opportunities for teacher feedback.)

Here I am going on and on about set for variability ???? because I think it's a big deal for early reading instruction even though it's rarely discussed. That's just one of the examples I have to point to demonstrate that Jan and Kari are right on point with the research.

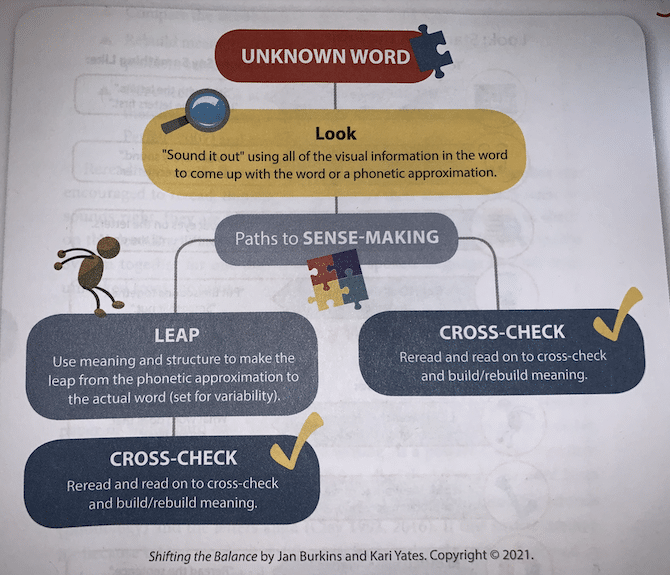

They understand that cracking the code on a given word is more than just blending letter-sounds together consecutively-even though that is an essential first step! They've gone to the woodshed with the old MSV paradigm for word learning and re-imagined it, in light of the reading research, including set for variability. In the diagram below, notice the process a reader is expected to go through in trying to identify a word.

See how the visual approach of attending to the inside parts of words (i.e., "Sound it out") is now the first step in the decoding process? If the child doesn't quite hear the sounds together in a meaningful way, then she must rely on her set for variability skill to deduce what word would make sense.

For example,

- She sees this text, "The cat went down the slide."

- She reads, "The cat went doan the slide."

- She ponders the mispronounced word, "down."

- She self-corrects, "down...The cat went down the slide."

- She's satisfied because the word "down" is a real word and it fits the sentence. She may also know more about the "ow" spelling than she did before. She may also be able to recognize "down" by sight next time, or at least in just a few more correct reading practices.

While I might create a different graphic to describe the process, this is an entirely plausible model for the complex process that a reader goes through to connect graphemes to phonemes to meaning. Importantly, this new model turns the old MSV on its head. What was terribly wrong about the old MSV cueing model was the relegation of the visual system to step-child status. They write,

"Many of us were taught (and in turn taught others) to avoid the dreaded words sound it out. This prompt has received so much criticism that, for many of us, its use invites self-doubt, and even shame. In fact, Kari's heart beats a bit faster at the very idea."

Now, however, Jan and Kari now have the visual system at the top of the pyramid...where it should be.

One caveat: In the diagram, the authors attribute the set for variability skill to meaning and structure but I believe it's also heavily influenced by phonology. In an article in Scientific Studies of Reading in 2016, Devin Kearns and colleagues note that set for variability "connects the phonological processes--those that lead to a recoding--and the semantic processes, those involved in locating lexical entries..." (Lexical entries are words in the mind's vocabulary bank.)

Some of us may be so disgusted with the damage done by those who stressed the M in MSV--at the expense of teaching the written code--that we want to never hear the concept again. Understandable. Yet, it's also understandable that those steeped in a 3 cueing worldview would more readily take up this revised model.

And when teachers who formerly revolved everything around Fountas and Pinnell's guidance, embrace this upside-down MSV model and the other profound shifts in this book, our children will be much more likely to learn to read.

# 3 The 6 Shifts Allow for High-Leverage Adaptations

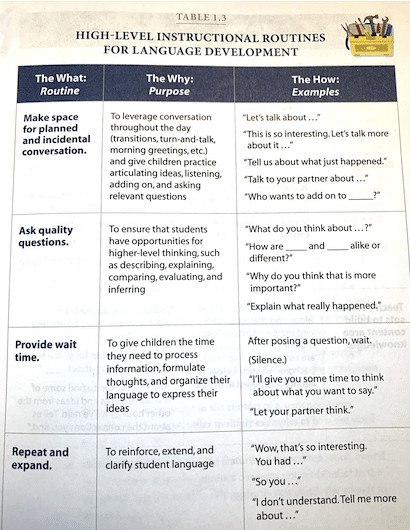

Even though Jan and Kari dug deep into the science of reading themselves, don't fret, reader. This book is an easy read with clear baby steps of what to do next. For example, for chapter 1, "Rethinking How Reading Comprehension Begins," we learn about 4 common misunderstandings:

- "Reading comprehension begins with print.

- Understanding spoken language and understanding written language are two different things.

- If children have strong oral language, they have most of what they need to learn to read.

- Successful comprehension in beginning reading texts means that reading comprehension is on track."

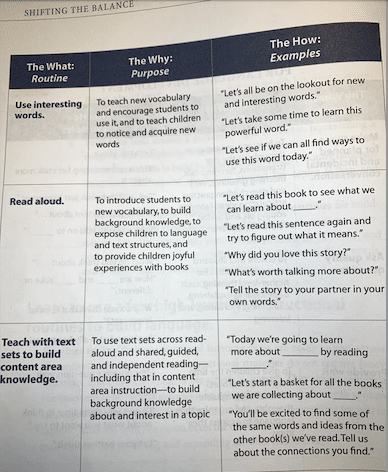

Once these misunderstandings are cleared up, the authors give us just a few high-leverage activities to adopt (see images below), such as ask quality questions, repeat and expand student language, and teach with text sets to build knowledge. These activities are doable and framed by both the logic of research findings and former routines in the balanced literacy classroom.

So, no need to study 1,001 strategies to implement tomorrow. ????

We, too, aim to deliver high-leverage activities here at Reading Simplified--to reduce the burden of teacher prep and make diagnostic-thinking much easier. Inside Shifting the Balance, Reading Simplified teachers will find practices that match up with many of our streamlined activities and principles.

For instance, Jan and Kari recommend

- interactive read alouds, rich elaborated conversations, and vocabulary study that connects phonology, semantics, context, and orthography

- cumulative blending, as we do in our Read It activity

- word chains, like our Switch It activity, with words of progressively harder phonemic difficulty (i.e, CVC to CVCC to CCVC to CCVCC, etc.)

- assessments to allow for responsive teaching

- learning high frequency words via a decoding route and

- aligning text choices with the specific phonics spellings the children are learning.

A Few Minor Points of Difference

These are just some of the many points of agreement. Of course, anyone who writes a book review this long must also have some points of disagreement. ???? Yes, I do and I brought this up with Kari and Jan. However, they are minor matters in light of the value and power of the whole book:

- In Shift 5, the diagram re-interpreting MSV and the simple view of reading doesn't seem quite how the model is typically interpreted to me. Breaking out Meaning and Structure (from the MSV model) and putting it into the Listening Comprehension domain of the Simple View of Reading implies that the word reading/decoding domain doesn't rely on meaning and structure, which is does.

- The routines to support problem solving words have many good pieces of advice; however, I noticed most every type of feedback is a question. Questions are fabulous! But we often find students make excellent progress when we tell them the 1 piece of information they are missing in order to decode an unfamiliar word.

For example, if a child who hasn't been taught the /ee/ sound yet, reads "street" as /stret/, we might prompt her with, "This is /ee/," as we tap our pencil between the 2 "e's." Read more about typical error prompts we use here.

Giving students feedback after word reading errors is one of the most powerful levers we use in the Reading Simplified system. So, I'd suggest that future editions include classic feedback cues to help developing readers overcome specific phonics or phonemic processing errors as they encounter them. - While I agree teachers need to find opportunities for student choice and to move rapidly into authentic texts, I don't find the dichotomy in Shift 6 between "read-all-the-words" texts and texts to "read-in-other-ways" to be that helpful for remediating the balanced literacy traditions that were less efficacious.

The authors suggest that teachers use decodable texts (which they label "aligned" similar to Wiley Blevins' term, "accountable" text) where students can read "all the words" as well as rich trade literature, where students "can read in other ways." I'm concerned that teachers from a balanced literacy background may overextend this 2nd category of "read-in-other-ways" (especially the "read" the pictures category) because they have less practical experience of seeing young children get rapidly into really reading the words.

This issue is a tricky one, indeed, because some systematic phonics classrooms might keep students in decodable texts exclusively for 2 or even 3 years. This practice can limit opportunities for set for variability practice, as I alluded to above. It also can reduce student motivation and engagement when they don't get to select trade books and/or learn to find books on their own. There is a tension between teacher control of books and student control of books. Where is the middle ground?

One way that Reading Simplified aims to reduce the tension is to get to early transitional texts rapidly. Mostly decodable texts certainly help, and we like to read both decodable and early transitional texts with students as early as possible.

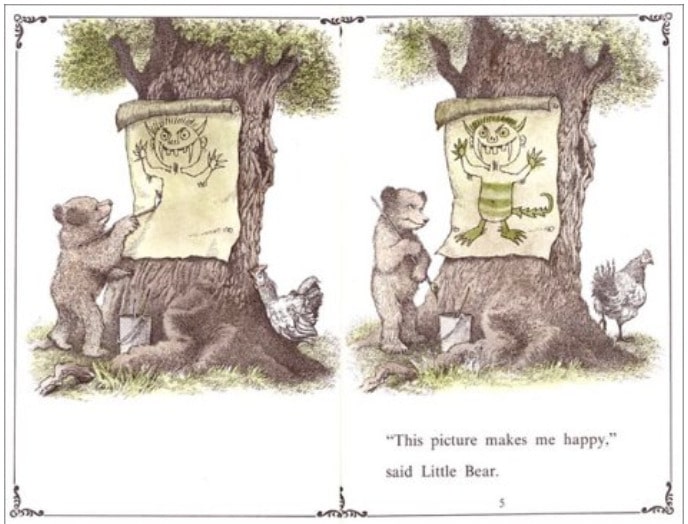

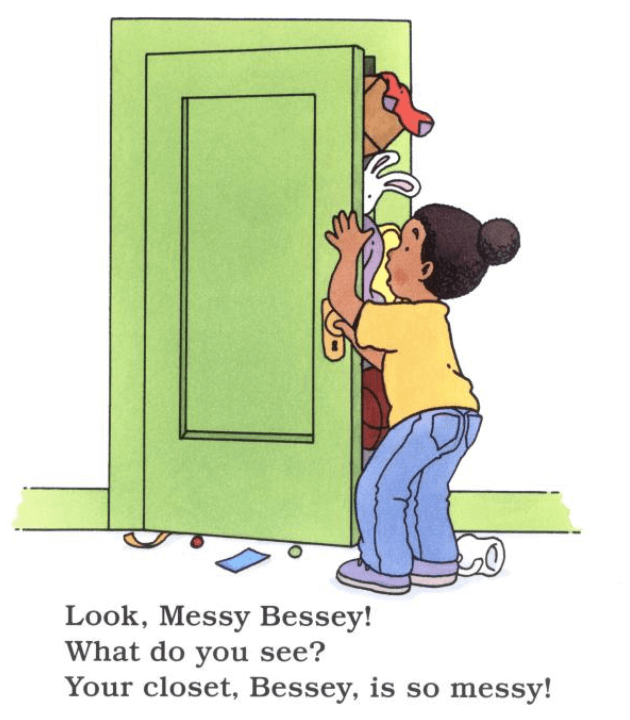

In our system, most kindergarten students can attempt--with a lot of teacher support--books like Little Bear, Messy Bessey, or Henry and Mudge by the end of the year. And most first grade students in their first year of Reading Simplified can get there by mid-first grade, with a little less support. (They may also be reading mostly decodable texts, at the same time, to reinforce the phonics focus of the week.)

At first the teacher can support students as they tackle these types of more authentic texts and then move into early chapter books, like Magic Tree House. This supportive experience usually empowers readers to begin to pursue similar books on their own....Ah! the glorious moment when student choice and self-direction leads to large volumes of reading practice!

Again, these issues of student choice and book type exist along a continuum and Kari and Jan have some smart diagrams to help us think about different texts for different circumstances. Sadly, this is an area of underdeveloped thought in the field because the reading wars have drawn such sharp lines between ways of selecting books. Despite my concerns, the 6th Shift of "Reconsidering Texts for Beginning Readers" does help us do just that--reconsider.

All in all, these are issues that I'd like to discuss further with Jan and Kari, but they are a mere drop in the bucket of the collections of 6 shifts and 27 misunderstandings that I admire and recommend.

In Sum, Change Is Coming

If you can't tell yet, Shifting the Balance: 6 Ways to Bring the Science of Reading into the Balanced Literacy Classroom, blew me out of the water. Decades of hostile walls between the "phonics camp" and the "balanced literacy camp" are starting to tumble. With this book, we have 2 leaders who've written about balanced literacy practices in the past acknowledge the urgent need to make shifts away from what they taught before. Wow!

Change is in the air....Other teachers and leaders with public presences have also acknowledged the need for change--with some sharing their own process of transformation:

- You can hear about the dramatic turn-around of Anna Geiger, The Measured Mom, in my interview with her here or through her new podcast series on the science of reading.

- The recent co-founder of The Right to Read Project, Margaret Goldberg, explains her transition from balanced literacy teacher to one who leads others with science backed practices. Watch her present here on our Facebook live show or read her blogs here.

- A Wisconsin teacher shares her frustration with not having learned how to teach reading in college by starting a facebook group--Science of Reading--What I Should Have Learned in College. In about 2 years' time, Donna Hejtmanek has led this group that's burgeoned to over 100,000 members--teachers and parents clamoring for knowledge that differs from what they find in their curriculum. Watch her tell her story here. Have you joined the group yet?

Given that over 75% of elementary teachers report using balanced literacy practices, we have needed guides to show us the path towards important improvements of practice. With their new book, Jan Burkins and Kari Yates have done just that!

Want to learn more? Pick up a copy of Jan & Kari's book and decide which shift you could make first. You'll also find many goodies that align with their suggested practices at thesixshifts.com.

Or, who else needs to know about this huge leap forward in BRIDGING the "sides" of balanced literacy and science of reading? Please let us know in the comments below.

[A token percentage of each sale can support the work of Reading Simplified at no additional cost to the buyer. And we only link to books and resources that we admire and have read/used.]