Speech to Print, aka Structured Linguistic Literacy, is a logical orientation towards teaching how to the read a complex alphabetic code, beginning with spoken language. Shared concepts, skills, and knowledge are foundational components of this approach.

Today I’m going to focus on the concepts of speech to print.

Speech to Print: Guidelines and Logical Schema

We know that English orthography is complicated, and so anytime something is complicated, it’s useful to have a schema.

Schemas are conceptual frameworks used in teaching complex subjects.

Schemas have to be logical for the content you're working with.

For teaching the alphabetic code, the four concepts below are a framework, or the instructional guidelines, to organize the code by.

Organizing by sound provides the logic for students to access the information they need, and this orientation reflects how the alphabetic principle was historically devised!

My friend Tami Reis-Frankfort of Phonic Books joined me to make the case that the concepts of speech to print are fabulous guidelines for teaching the complex code of English.

Simply put, start with the sounds in words students already say, then connect those sounds to letters.

Tami and I were honored to be guests on the Melissa and Lori Love Literacy podcast hosted by the inquisitive, generous team of Melissa Loftus and Lori Sappington to help answer the question, “What is Speech to Print?”

It was their 147th episode!

Melissa and Lori always talk about big topics, but this episode was part of their “Hot Topics” in the science of reading series.

They teamed up with Anna Geiger of The Measured Mom and Triple R Teaching Podcast for several weeks as well…

For that series, Anna produced 2 short episodes on a topic and then a lengthier conversation with Melissa and Lori dropped on Fridays.

It was like a virtual, audio text set to build coherent vocabulary and background knowledge on all things Speech to Print for a week!

If you have time, enjoy the podcasts we link below. If not, let’s recap!

Triple R Teaching Podcast related episodes:

What are the guidelines that underlie a Speech to Print approach?

Importantly, as Tami says, these speech to print concepts…

Concept #1: Letters spell sounds

The first concept in speech to print approaches is that letters represent the sounds in spoken words, a reflection of the alphabetic principle.

We reveal the alphabetic code to children by drawing their attention to the sounds that letters represent first, rather than letter names.

We want them to hear the sound and then attach a symbol to it.

And so we can start with their oral language and the child's worldview. They know way more about language than print as beginners.

We're not starting with phonological or phonemic awareness in isolation either.

We're not starting with any sub-skills in isolation. Integrate, don't isolate!

...are the guidelines for everything we do, the guidelines for how we teach. They're the guidelines in how we introduce the language we teach--the error correction all the way to this is how it works, really. Not only this is how each part works, but this is how the different parts work together.

For example, say a word like "mat" and have students listen for the initial /mmm/. Then match "mmm" to the letter "m." This teaches the alphabetic principle, letter-sounds, blending, and segmenting - early reading skills. Cognitive scientist Stanislas Dehaene shows these letter-sound connections enable fluent reading. So focusing instruction time on linking sounds to print is key.Tami Reis-Frankfort of Phonic Books, Ltd.

Tami explained that we're actually putting them all together in an integrated way to help them understand this whole concept of the alphabetic principle, because it's not natural for the child to intuit this.

If our written language is a code for sounds, we need to show them the code. And the access key for that code is the phoneme.

In doing so, children play with the sounds in the language they already know and start to lift meaning off the page because they understand the code and how all the pieces fit together.

We start with sound. The information isn’t in the letter names.

Stanislas Dehaene is a renowned neuroscientist known for his work with reading and the brain.

He highlights that teachers need to be focused on sound to letter bonds.

His book Reading and the Brain explains the reading process in depth.

Video: How the Brain Learns to Read.

Dehaene emphasizes that we should prioritize teaching the automatic recognition of letter-sound bonds to build successful reading development.

So how does a teacher begin to help her students secure letter sounds tomorrow?

(Phonic Books has workbooks that accompany their early series lists for word building.)

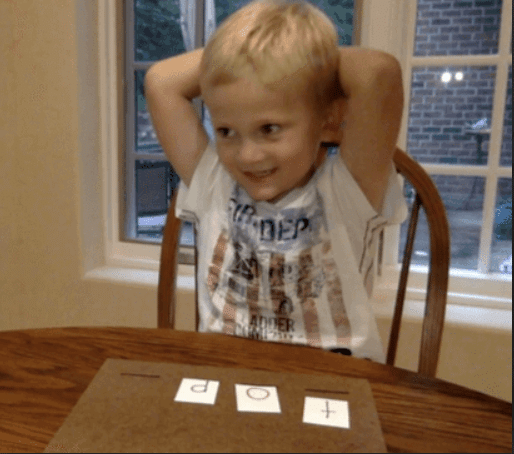

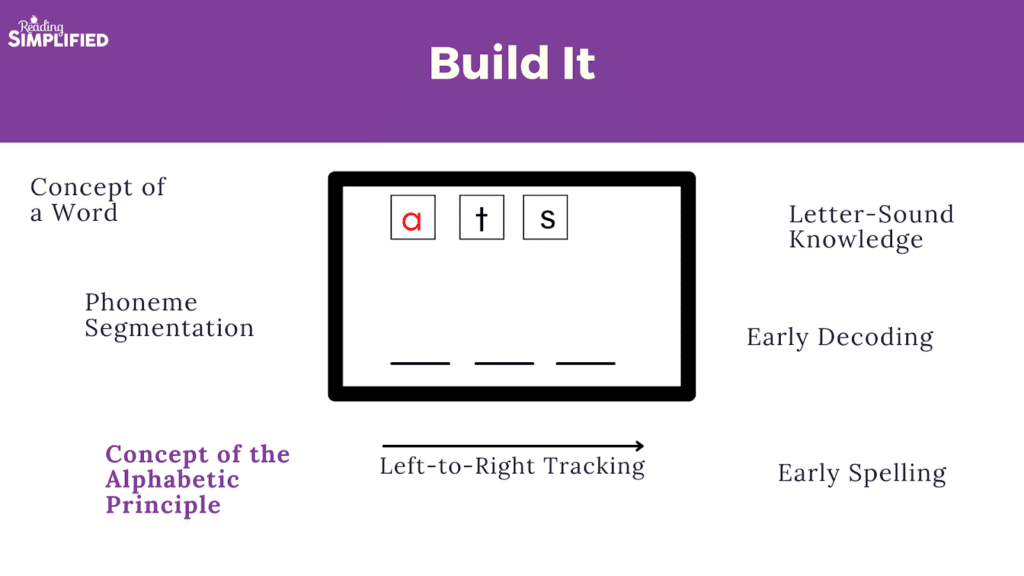

In Reading Simplified we often kick off instruction for beginniners with a simple word building activity called Build It.

An activity like Build It incorporates so many skills all at once! More importantly, it is coherent and meaningful for those with limited to no experience with print.

Error correction with the activity is just as important as the activity itself. That's often actually how we reveal the alphabet principle, phoneme segmentation, and letter-sound knowledge to absolute beginners–by drawing their attention to the one insight that they need to complete each task in the game. The video of Build It above demonstrates how much a preK child can learn just through these back-and-forth interactions with a teacher.

Everything goes back to the idea that letters spell sounds and the letters represent phonemes.

So think about it…if we're aiming to get those letter sound bonds that we know we need to develop super automatic, should we be spending a great deal of time on phonological awareness activities which are not at the phoneme level?

[I talked to Dr. Susan Brady about all of that here the research updates surrounding phonemic awareness instruction.]

We also delay the use of letter names in instruction in Speech to Print Approaches, or at least reserve those for a different time of day while we teach letter formation and handwriting instruction.

But it’s hard to avoid, especially in the United States, so our recommendation is to at least work on letter names at a separate time of day and in association with handwriting instruction in the very beginning stages of learning to read.

Here are some other resources to check out about this letter name/sound tension:

Concept #2: Sounds can be represented by one or more letters

Some sounds can be represented by one, two, three or four letters.

There's one or more letters making that sound.

Tami expertly shared that,

English happens to be one of the most difficult scripts of all scripts, and it's a result of historic loaning and borrowing and taking words from every different culture. What this principle or this concept means is that English has a very complex alphabetic code. So it's all the more reason necessary to teach it in a very systematic and logical way, and to organize it in a logical way. And that goes back to that schema we were talking about, organizing in a way that it's understood. How do we organize all these different spellings, 165 or more?

Tami Reis-Frankfort of Phonic Books, Ltd.

Our colleague Nora Chahbazi of Evidence Based Literacy Instruction (EBLI) presents it this way (Individual programs may reorganize the order of concepts. For EBLI, what we share as Concept 2 is shared as Concept 1.):

Complicated things need to be taught in a logical, explicit, systematic way and Nora shows this brilliantly!

For example, we start with one-to-one correspondences and words like “cat” in which every letter spells one sound.

From there some programs, both Reading Simplified and Phonic Books, then go into double consonants rather quickly.

Here’s a look at Phonic Books progression progression, and below, Reading Simplified’s Kindergarten Streamlined Pathway.

The leap isn't very big to understand that if “l” by itself is /l/, two “l”s also spell the sound /l/. So that's not a very big step and very young learners handle it beautifully after activities such as Build It, Switch It, and Read It.

And then from that step onwards, we introduce that two different consonants can spell one sound, so the letters “s” and “h” spell “sh”, as in “ship.”

Once we've done two letter spellings, we can then immediately move to three letter spellings like the /ch/ in “tch” as in “ditch.”

We try to reveal as much of the code as quickly as possible, but we don’t dump it on students all at once.

What we do here at Reading Simplified and most Structured Linguistic Literacy programs is a gradual revelation.

So we give students order from a lot of information.

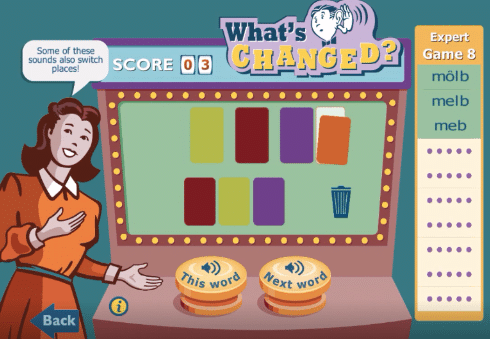

In the early phase of a reader's development, one way in which we reveal the increasing complexity of the code is through word chaining activities like our Switch It. Each phoneme, or sound, is represented by a separate card. The child begins to process less in terms of letter names and more in terms of phoneme-grapheme relationships. This is right where we want him! 😉

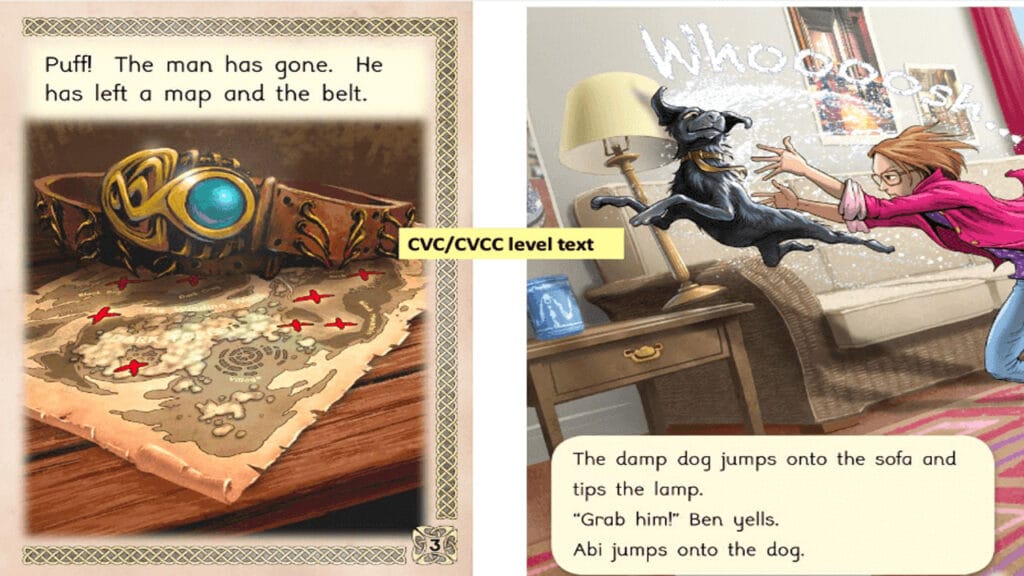

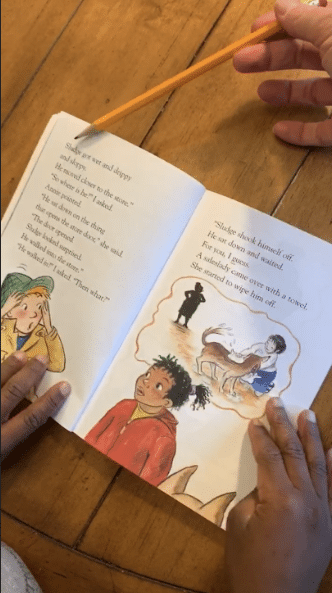

Additionally, Read It also helps reveal this information to students, along with a lot of connected text reading in our 3-component lesson plan.

Resources:

Concept #3: Sounds can be spelled different ways

This was a revolutionary emphasis of Diane McGuinness and a lot of Speech to Print programs have been born out of her work.

She organized these four principles…showing us how the code works…going from sound to symbol.

It may seem complex but we release the information to beginning and striving readers in a logical, though rapid, progression.

In many Speech to Print programs starting with high frequency spellings is common.

We can do this with the “advanced code” or what you might know as long vowel teams as well.

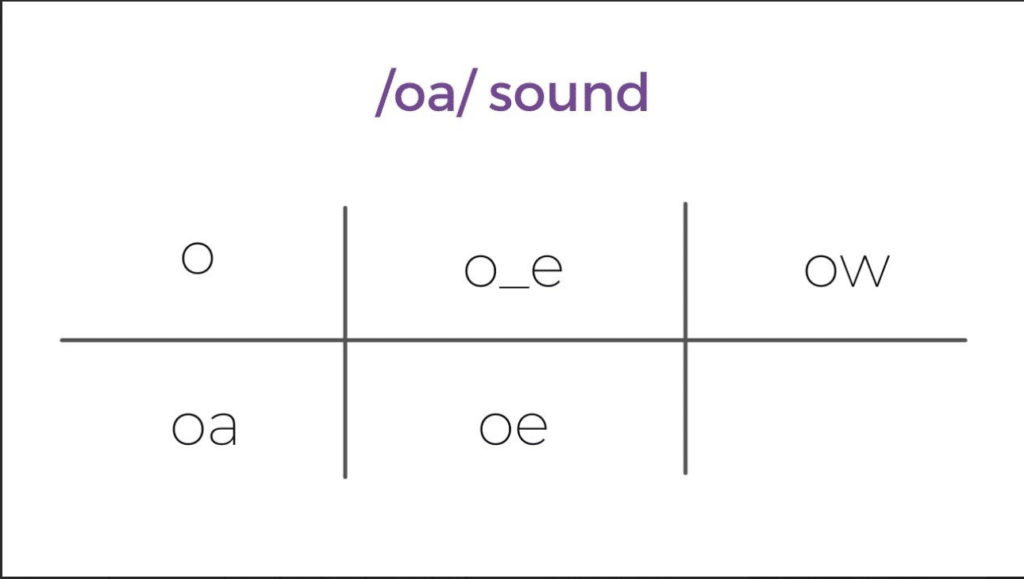

For instance, with Reading Simplified, I start with a sound /oa/ and it can be the /oa/ in in “go,” the /oa/ in “show,” the /oa/ in “boat,” the /oa/ in “home,” and the /oa/ in “toe.”

Kids can handle this!

High-Frequency words, such as “go,” “show,” and “home,” and high frequency sounds are where we start.

There are others like the /oa/ in dough, but we just don't begin there. You could, for sure, give them all or many of the spellings attached to the sound at once, but that particular set is low frequency.

If 5 sounds all at once gives you whiplash, I get it! You may then start with one sound and 3 spellings like in this Phonic Book’s series of Dandelion Readers.

However, with my work with students privately, through the IES-funded research intervention Targeted Reading Intervention and in the Reading Simplified context, I find that students really can get the concept that one sound can have multiple spellings.

And it’s so important that they do!

The concept gives them order and organization from the first time you introduce it, or at least within a few days or hours. It's logical and orderly, unlike dripping out just one grapheme by grapheme for weeks on end.

And of course, there are a lot of opportunities for review through games still focused on sound.

What happens with traditional print to speech, or print to sound programs is that the child can't possibly figure out this logic because in September it would be the “o” by itself like in “go.” And then two months later the students encounter the spelling “oa,” and three months later they are taught the “ow” in “snow.” And one might never see “oe” in one's first year.

Only the very swiftest kid can cobble together this drip, drip, drip-approach behind the scenes on their own.

Or we could just present it all together at once, which is what most Speech to Print programs do.

It’s logical–a common sense way to be in alignment with what we know about how the brain learns to read.

So if you are aware of these concepts, the whole way you teach is scaffolded. The children are following your closely controlled guidance and feedback and they're not surprised when they get to the word “dough” because they know that in English, a sound can be spelled by one to four letters, and that this is one of the graphemes that has four letters.

Slices of evidence, not a slam dunk.

But we have less evidence on if you organize your reading instruction this way per se, then you’re guaranteed to get a certain level of outcomes compared to not organizing instruction this way.

We just don't have that level of sophistication yet with the research on programs or individual elements.

We have so much more research on how the brain learns to read then we have research and thinking on the linguistic system.

And I think that's what Diane McGuinness did so well, teaching, “Because this is the way the system works.”

She presented a logical common sense way to be in alignment with what we know about how the brain learns to read.

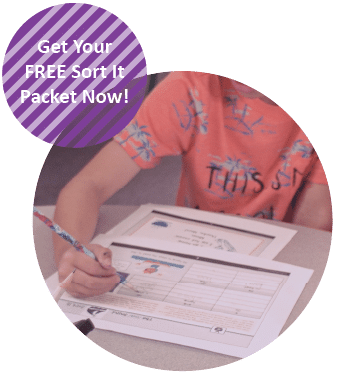

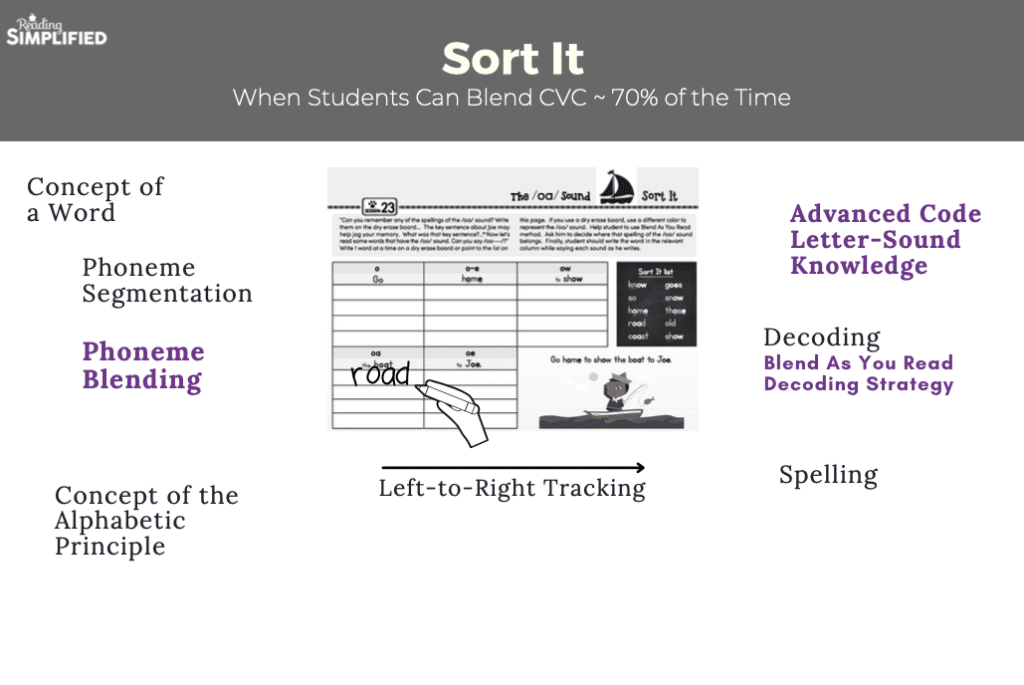

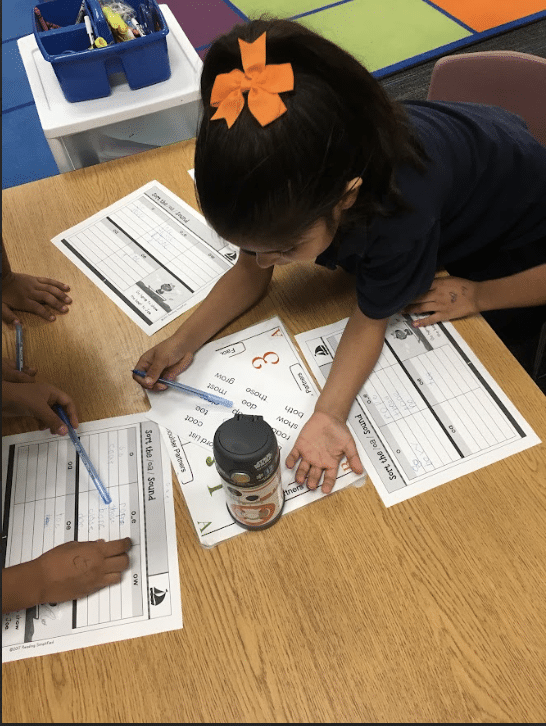

Reading Simplified’s Sort It activity is what supports instruction the most for this concept once we get to the advanced code.

And we use mnemonic sentences such as, “Go home to show the boat to Joe,” to help students remember each spelling.

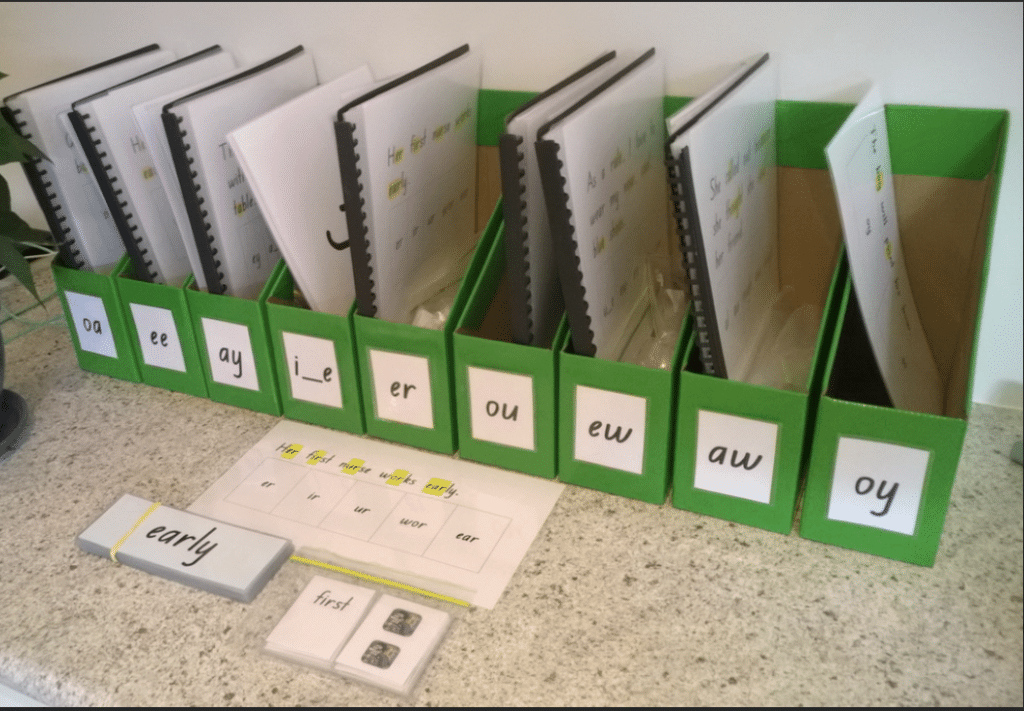

Notice below how former Reading Recovery teacher turned Reading Simplified tutor (in “retirement”), Anna Linard, organizes her decodable texts by sound. Anna works with over 50 students 1-on-1 or with their siblings every week, !! and she says that, in part, she's able to do this because the Reading Simplified is so streamlined.

Phonic Books also has great sentences One Sound, Different Spellings Sentences – Phonic Books as well.

Resources:

Concept #4: Spellings can be pronounced in different ways

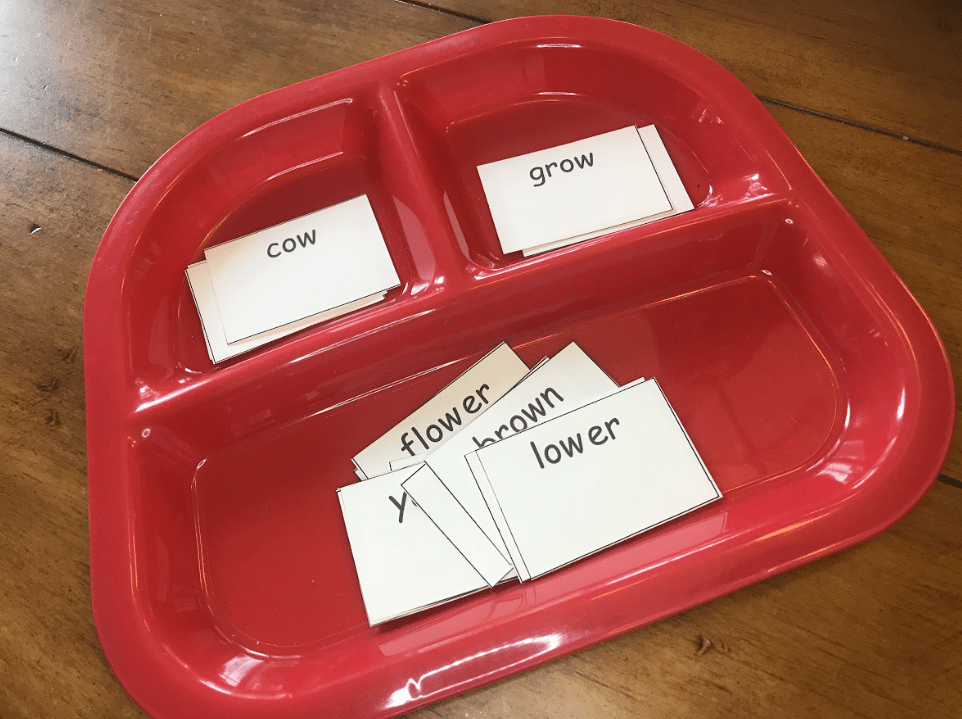

The spelling “ow” can sound like /oa/ in “snow,” and it can sound like /ow/ in “how.” Tricky business!

But it's not that hard. We teach this concept explicitly.

Our favorite way to teach this concept is through sorting activities and games. You give students a list of words with the two sounds that one spelling can represent, and they have to read and sort them out in order to see for themselves.

Sorting helps demystify the complexity of the code to make phonics stick.

Phonic Books also has sentences to help with this One Spelling, Different Sounds Sentences – Phonic Books.

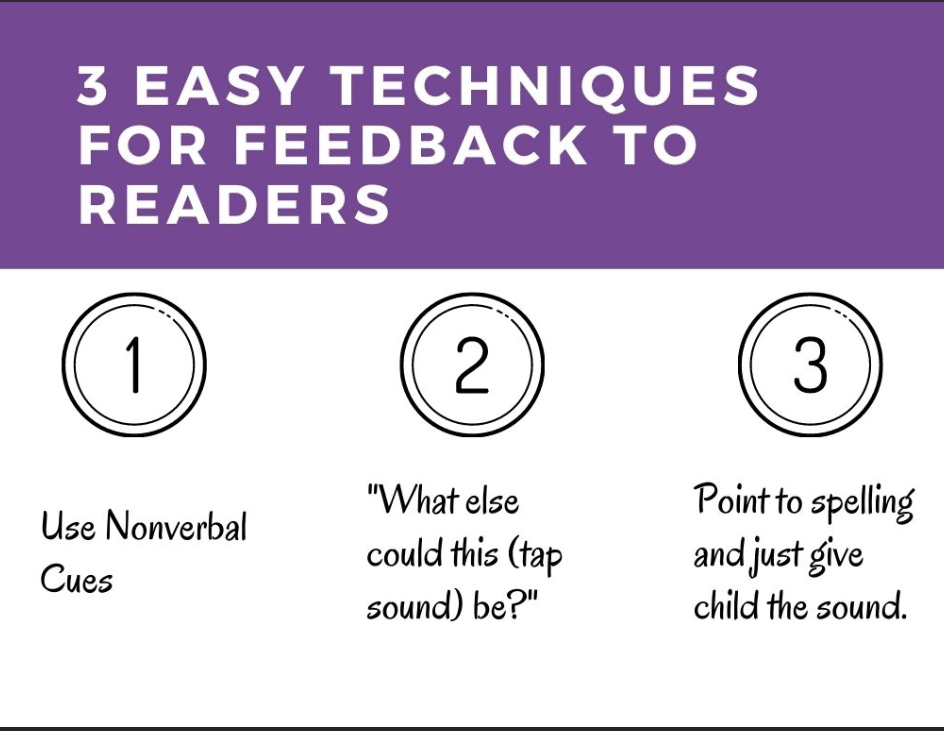

Now this is very important in reading because often children make mistakes here: They might read the word “snow” as if it rhymes with “how.” You can tell them, “That can be /ow/, but in this word it's the other one. Try again.”

No problem, no failure. It's just the way it works.

And what research is showing us is that this flexible strategy is actually another second decoding skill (after blending) that kids need to acquire.

Just in the last few years, there's been a flurry of research on this concept of Set for Variability, which is a big term that means mispronunciation correction.

In other words, if the kid reads “snow” but it rhymes with “how,” she's certainly mispronounced it. But then she has to have the cognitive flexibility to play around with the sounds in that word to come up with the correct pronunciation rhyming with “toe.”

And that's different than blending the sounds because the child actually blended the sounds correctly. In the first decoding skill s-n-ow (as in how)…blending is not a problem here. That's the first decoding skill.

The second decoding skill we have to build is this set for variability. At Reading Simplified we call it Flex It.

“Yes, that could be /ow/ but “snow” is not a word.

What else could this be?

We try to put the burden on students to develop that cognitive flexibility. Thus, we challenge them to try one sound, and if it doesn't create a meaningful word, then we prompt them to try another sound. Indeed, with the Targeted Reading Intervention, we called this Set for Variability strategy, “Try One Sound.”

But what if you prompt them to try again, and they're still unsuccessful?

No worries! Then you simply say (while tapping the spelling with a penci),

“Well, this is /oa/.”

As mature readers, when we come to a funky pharmaceutical word that we've never seen, we play around with the sounds. We don't know if it's /ow/, or /oa/, or /oo/, or /uh/, so we have to play around with the sounds.

We need to build the rapid processing of phonemes and graphemes and words to enable student to succeed with this cognitively demanding skill of Set for Variability. Phonemic awareness not only unlocks the code in the early days of a reader's development, it also develops the readers' knowledge of the code.

And as we develop our knowledge of the code, we get better and better phonemic awareness.

It’s a reciprocal, integrated, connected relationship between phonology, orthography, and meaning. Think of the book If You Give a Mouse a Cookie for how these sub-skills interact and depend on one another. 😉

Resources:

- One spelling-alternative sound Infographics|Phonic Books

- Hi-Lo Books That Really Work to Engage Older Readers | Reading Simplified (The Talisman 2 Series is a great example of suffixes that have same spellings but different pronunciations. For example Book 8 with the suffix “sion” as /shun/ like in “tension” while in Book 10 the focus of the same suffix pronounced as /zhun/ as in “illusion.”

Explicit instruction, absolutely! But how much?

You need to know a certain amount of the code, to be able to play around and make a choice.

There's no agreement in the field on how much of the code you need to teach, but you need to teach a significant amount of it.

So a traditional phonics approach would suggest that a child can't know what sound to produce when they come across an unknown word without having a rule or syllable type to apply.

But we know that that's not how the brain learns to read.

The brain observes patterns and subconsciously can predict things.

So if I show you the word J-E-A-D, which is a nonsense word, you'll probably read it as “jead” has in “head” because you have learned the pattern through repetition of reading from “dead,” “lead,” and “read.”

Even though that's a lower frequency sound for “ea”. But when you attach “ea” to the “d” you've learned that subconsciously, we can extrapolate it because our brain is observing patterns.

And this is where we get into some tricky things because in the science of reading movement, we've been fighting for years against the notion that reading is natural like language.

Tami and I tried to make the case that we have to explicitly teach things and help kids combine their existing language network to this new printed network.

Explicit instruction is absolutely critical.

And yet we are not actually teaching all of the phonics information.

We're not teaching all of the words and every possible phoneme grapheme relationship.

The child is picking things up through observing patterns because they've been exposed to this information in real reading and they've played around with the sounds and they came to the word “bread” for the very first time.

They tried “breed” and it didn't make sense in the sentence. So then they flipped it to “bread” and their brain is off to the races.

And yet if you ask the child, “Is there a rule for when “ea” should be /ee/ and when it should be /eh/?” they won't know, because it's a subconscious thing that's happening in the background.

So we have to begin the process of teaching reading explicitly and consider some additional tenets laid out by Dr. Mark Seidenberg.

And we also have to trust that the brain is observing a lot of patterns through just exposure to this information, constant exposure to the code and playing around with it.

And then that leads into this self-teaching theory, which is well-researched.

It got some significant attention in an excellent paper from David Share in 1995.

But then there's been other studies that have validated it.

Basically the self-teaching theory states that we are not explicitly teaching kids every sound, or every grapheme, every bit of phonics information.

We're not teaching them every word, rather, they're mostly self-teaching themselves through reading, trying to play around with sounds and words and getting more and more knowledge every day.

What information do we need to read words?

So all that's needed is sufficient phonemic awareness, sufficient phonics knowledge, and a decoding strategy. Just three things.

Students don't have to have all of the phonics information.

Instead of scaring us as teachers, this should be exciting!

We should be eager to explicitly teach our kids how the code works, the alphabetic principle, teach them some core sounds that are high frequency and then give them a lot of opportunities to read where we guide them with feedback, corrective feedback.

And this is another element of the Speech to Print approach that's important…

…because we're organizing the code by the way it's designed and we're giving kids these hooks, they actually learn the code much more quickly so we get into real texts and have more opportunities for statistical learning.

Let's Wrap Up!

So all of these things that are developing in the research world about statistical learning and set for variability and self-teaching, they all show us a path towards more and more implicit learning.

This really resonated with Melissa and Lori and I hope it does with you!

Melissa shared…

…It takes stress off of students if they don't have to remember all those rules. But I would say it takes stress off the teachers too, to not have to answer the, ‘Well, why is this one spelled this way versus…” I don't know all the ‘whys’. And you don't have to know, to be able to just say there are different ways.

Melissa of Melissa & Lori Love Literacy

Lori shared her aha!

Yeah. I think that the set for variability is the thing that to me really gives me the permission to say, Okay, let's try it. Let's see if those letters make a different sound. Let's try. And it makes me feel more confident as a teacher thinking about, I guess what I said before, giving myself the permission to not have to know all the rules. That feels really scary to me. And I know some of the rules, but I don't have all of them memorized. And I think that…to give yourself permission to, if you don't know a rule, even if you are teaching in a "print to speech approach," I think it's okay if you're not sure, to just say, There's lots of different ways that this could be spelled. And I think that's okay.

Lori of Melissa & Lori Love Literacy

There are tons of ways to learn more about each of these concepts and examples of how to use them at www.phonicbooks.com and www.readingsimplified.com.

Hope you’ll keep exploring with Speech to Print programs. You’ll find another presentation here: Speech to Print: Is There a Third Way?

The Reading Simplified Academy can teach you a Speech to Print system that you can use flexibly with many Phonic Books series and other mostly decodable books.

Now It's Your Turn!

Have you tried a speech to print, linguistic phonics, or structured linguistic literacy approach? What have you found?

If not, what questions do you have? Please let us hear from your experience below!